Last week members of the museum team conducted exciting research on the ground in Kenya. Their aim has been to survey the remains of British colonial detention and work camps established during the 1950s to incarcerate suspected Mau Mau fighters and supporters. There are very few locations where the physical remains of camps still stand, but this fieldwork has hugely aided the museum’s project in collating a more accurate history of the conflict. Sites such as the Aguthi Works Camp visited by our team were at the epicentre of what the British colonial authority dubbed their ‘rehabilitation’ programme. This programme, along with the network of works and detention camps built to support the process, was nicknamed the ‘pipeline’ and was a vital component in the colonial government’s response to the Mau Mau. So, what were the aims of the pipeline and what did it entail? We thought it would be a good idea to further delve into this notorious programme and to determine what ‘rehabilitation’ in this conflict really involved.

View of Aguthi (Mungaria) Work Camp, from J.M. Kariuki’s 1963 book ‘Mau Mau Detainee’.

The same view, taken on the Museum’s research trip to Nyeri. Moha, above, stands in the former location of the watchtower.

Thomas Askwith, Commissioner for Community Development in Kenya, developed the pipeline in 1953. It was a large-scale system to ‘rehabilitate’ suspected supporters and fighters of the Mau Mau movement. The notion of a ‘pipeline’ was used to denote the progression of individuals from initial detention to their ultimate release. The concept of ‘rehabilitation’ was borne from the fact that, in an effort to delegitimize their struggle, the British colonial administration declared adherence to the Mau Mau cause as a mental disease. As a result, Askwith designed a process aimed to ‘cure’ the Mau Mau of this disease through a specially designed programme of hard labour, typically involving ‘training’ within a particular trade such as agriculture or carpentry, followed by re-education and a restoration of what he considered to be British moral values.1

The pipeline system – a network of detention centres and works camps through which the British colonial administration moved their detainees – was constructed to support this process. Askwith created a programme focused on hard work and education in the hope of equipping detainees to contribute to colonial Kenyan society upon release. The pipeline became a powerful propaganda tool to validate the British response to Mau Mau as the system had been legitimised through the influence of psychiatrist Dr. J. C. Carothers and the involvement of scientist Louis Leakey. Carothers had argued the notion that Mau Mau was a symptom of psychological shock to modernity whilst Leakey characterised Mau Mau as a religion orchestrated by ‘evil men’. Therefore these notions along with Askwith’s proposed ‘solution’ to Mau Mau substantiated the British response. As military operations ramped up in 1954, however, this programme was soon outpaced due to the soaring numbers of detainees.2 Askwith’s pipeline was soon converted into a system of punitive detention, torture and collective punishment.

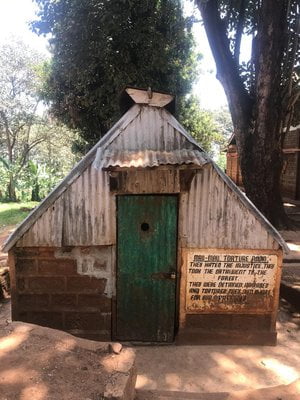

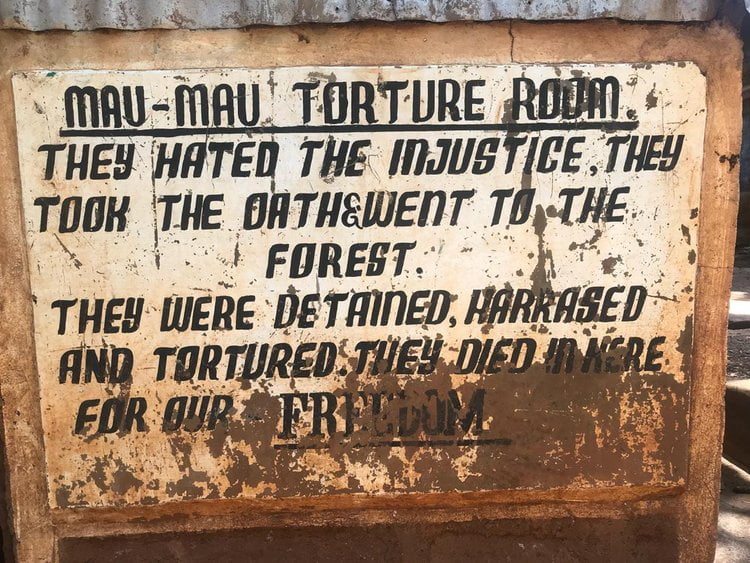

Former torture room at Mweru Works Camp

In theory and in practice, it was vital that any Mau Mau adherent confess and renounce their oath in order to progress through the pipeline towards eventual release. As Mau Mau oaths, however, were binding – and a condition of taking the oath was that it was not to be revealed – the British colonial administration relied upon a brutal process of interrogation to determine the individuals’ involvement with the Mau Mau movement, and ‘extract’ a confession. As confession and renunciation of the oath was the first step towards ‘cleansing themselves’ of the Mau Mau ‘infection’ 3, the interrogation process became central to ‘rehabilitation’. From the point of confession – which was not guaranteed – British colonial officers decided which category the individual would join; the Blacks, Greys or Whites. These groups reflected the involvement of the individual within the Mau Mau and determined how easily they believed they would be ‘rehabilitated’. Those within the Black category were primarily the leaders and those most deeply involved, whereas the White group consisted of individuals mainly cleared of involvement during screening. This category system was used to monitor the progress of those detained, and framed the process of ‘rehabilitation’. 4

With Askwith’s plans now converted into a harsher system of punitive detention, it was decided that he would turn his attention to the ‘community development’ for those outside detention; those in the reserves and the emergency villages. And what had begun as a short-term aim of ‘rehabilitating’ those caught fighting for the Mau Mau, soon became a long-term process of social reengineering amongst the wider population.

This illustrates that although historians have often implied that ‘rehabilitation’ was a process exclusive to male and female detainees, it was in fact an approach implemented far more widely than the detention centres alone. Indeed, under the guise of this ‘community development’, the ‘rehabilitation’ programme formed the bases of youth camps such as the Boy’s Scouts as well as women’s development organisations such as Maendeleo ya Wanawake. My own research explores the involvement of the British Red Cross and colonial officials in teaching African women the skills very much expected of British women during the 1950s. Kenyan mothers attended classes on keeping their homes clean, washing their babies correctly as well as acquiring sewing and crocheting experience. These classes worked as a form of ‘rehabilitation’ and conditioning to steer Kenyan women’s focus from the Mau Mau cause and as illustrated yet a further attempt to impose Western gender expectations on those within British colonies.

Former solitary confinement cell in Aguthi Works Camp, now Kangubiri Girls School. Windows were added by the school after independence.

Barbed wire in the roof of the solitary confinement cell pictured above.

In 1953, ‘rehabilitation’ may have aptly described the process designed by Askwith and his team, as they saw it; a training and education programme designed to rid individuals of the Mau Mau ‘curse’ and restore them to the model moral citizens required for colonial control. But as I sit writing this piece, I wonder whether we are using the most appropriate terminology in our assessments of the pipeline or merely inheriting the names and phrases for this time that served to conceal the true nature of British colonial control. If we do not sufficiently interrogate and dismantle the language of colonial rule itself, are we, as historians, going far enough to challenge the power structures and the narratives that we are seeking to understand.

Though the programme may have started out with plans for ‘rehabilitation’, and though it may have contained elements of training and education, there is no question that ‘rehabilitation’ escalated to include mass detention without trial, violence, torture and other egregious abuses; not just within the detention centres, but within even everyday life in the emergency villages. Now this is known to us, perhaps it is time to deploy a term that can more accurately convey the realities of this process.

Beth Rebisz

1 Rhodes House Library, Mss. Afr.s.2100, Thomas Askwith, Correspondence, 35-36.

2 Paul Ocobock, An Uncertain Age: The Politics of Manhood in Kenya (Ohio, 2017), 176-179.

3 Thomas Askwith (Edited by Joanna Lewis), From Mau Mau to Harambee: Memoirs and Memoranda of Colonial Kenya (Cambridge, 1995), 111.

4 The National Archives, Foreign and Commonwealth Office 141/6426, Official Committee on Resettlement; Papers and Agenda 1955-8, 7.