Afterlives

Across Africa colonialism, slavery, and racial oppression relied on incarceration, imprisonment and restriction.

Slaves were shackled and confined. Prior to the advent of full colonial political control debtors and others who disturbed the smooth running of trade were imprisoned by European traders. Once colonialism took hold incarceration was seen as a priority for colonial rulers, and prisons were often the first buildings they erected. Later, imprisonment was a key tool of dealing with resistance to both colonial and apartheid rule.

These sites of incarceration, the structures and spaces built to intimidate, isolate, restrict, punish, and exploit, persist even when their violent usage has ended.

Colonial structures, both physical buildings and administrative processes, have remained after the end of colonial rule. Incarceration remains a key form of control and punishment and continues to shape Africa’s politics and societies. Therefore, many colonial era prisons and camps continue to be used for carceral purposes. Others, however, have been repurposed and are now used for different activities.

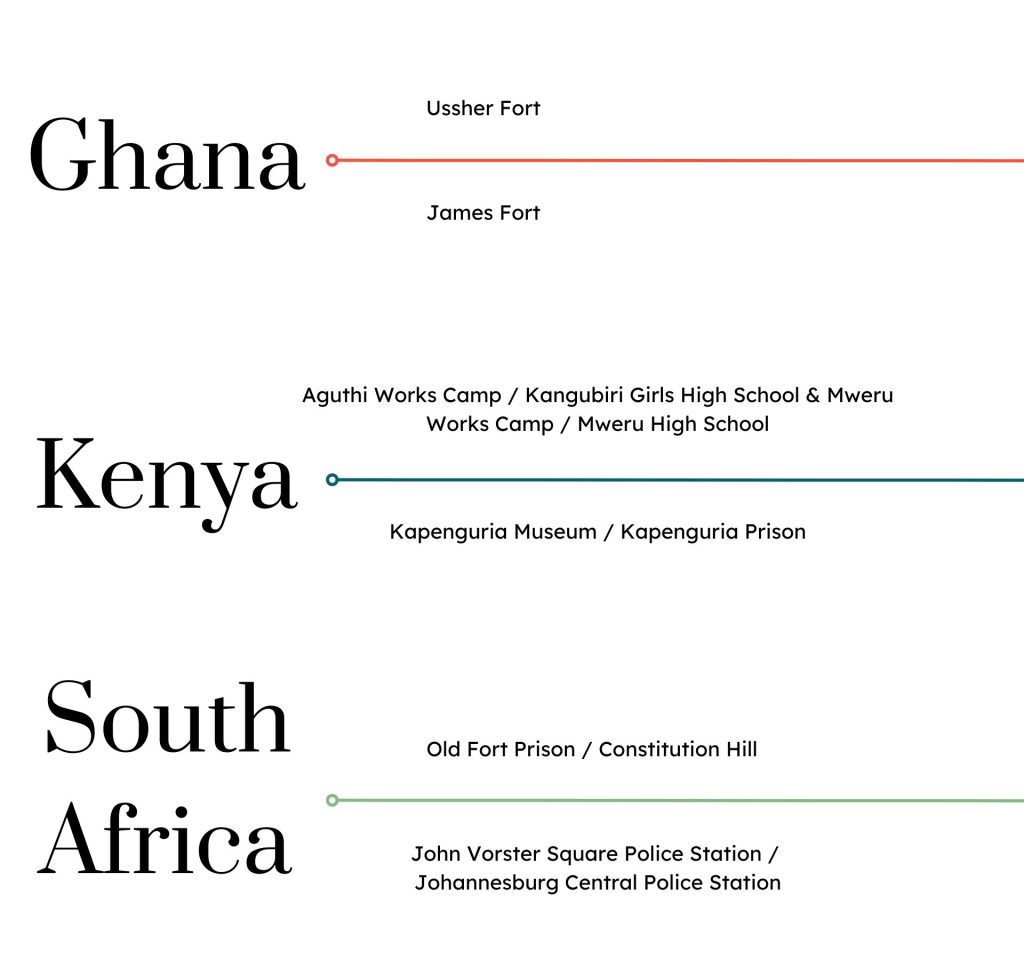

Based on research conducted in Ghana, Kenya and South Africa, this exhibition explores:

- What happened to sites of colonial incarceration after colonial rule ended?

- What do their Afterlives look like?

- How are the histories of incarceration at these places remembered?

- Does this history of incarceration matter today?

“It is said that no one truly knows a nation until one has been into its jails…”

– Nelson Mandela

Select a heading below to jump to a section of the exhibition:

Project Sites

Ghana

Ussher Fort & James Fort

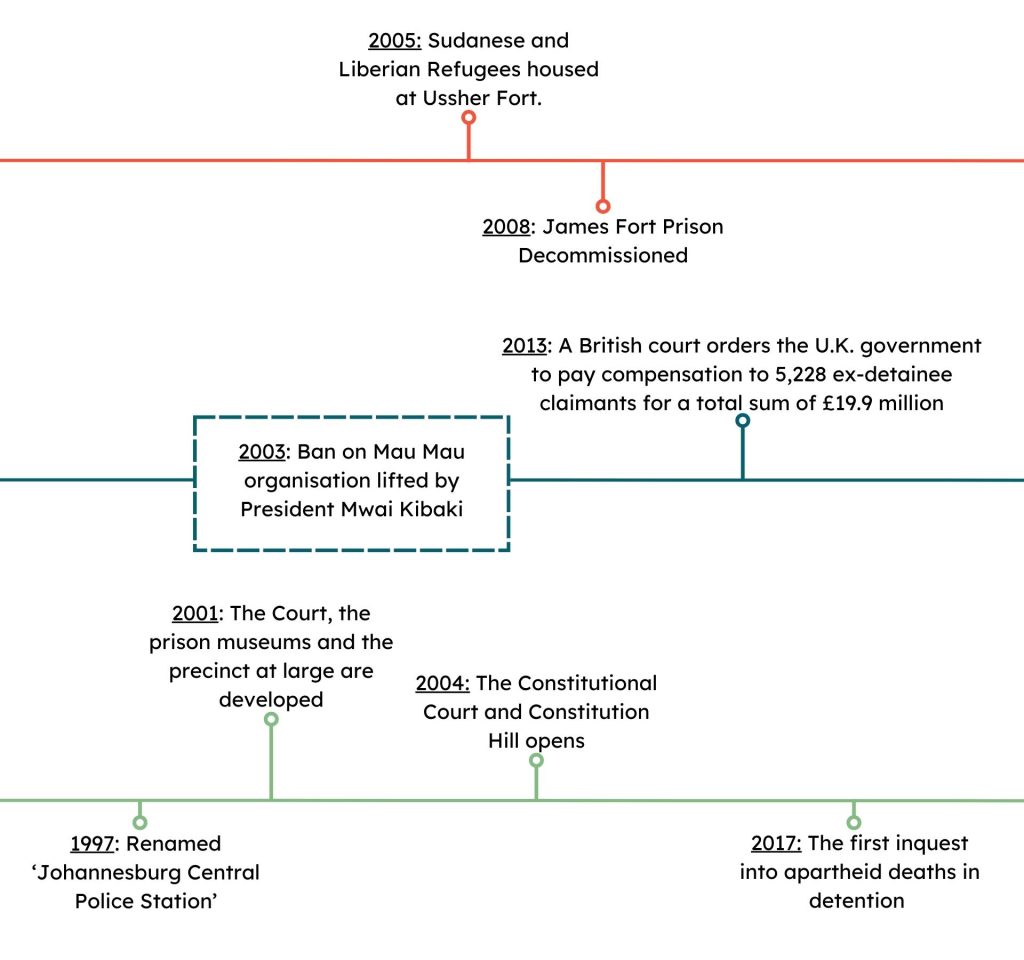

Ussher Fort and James Fort are situated within Ga Mashie. The Ga were initially resistant to traders building in their area but in 1649 allowed the Dutch West India Company to build Fort Crèvecoeur. In 1672-73, the English Royal Africa Company followed suit building James Fort nearby. In 1867, Fort Crèvecoeur was transferred to the British and was renamed Ussher Fort. The growth of trading forts along the coast of Ghana was linked to the trans-Atlantic trade in goods (esp. Gold) and in people. The ruthless slave trade brutalised millions and altered the globe in ways which still resonate today. Locally the forts galvanised urban growth and change. Ga leaders could sometimes be freed slaves, sometimes be slave traders and sometimes were both.

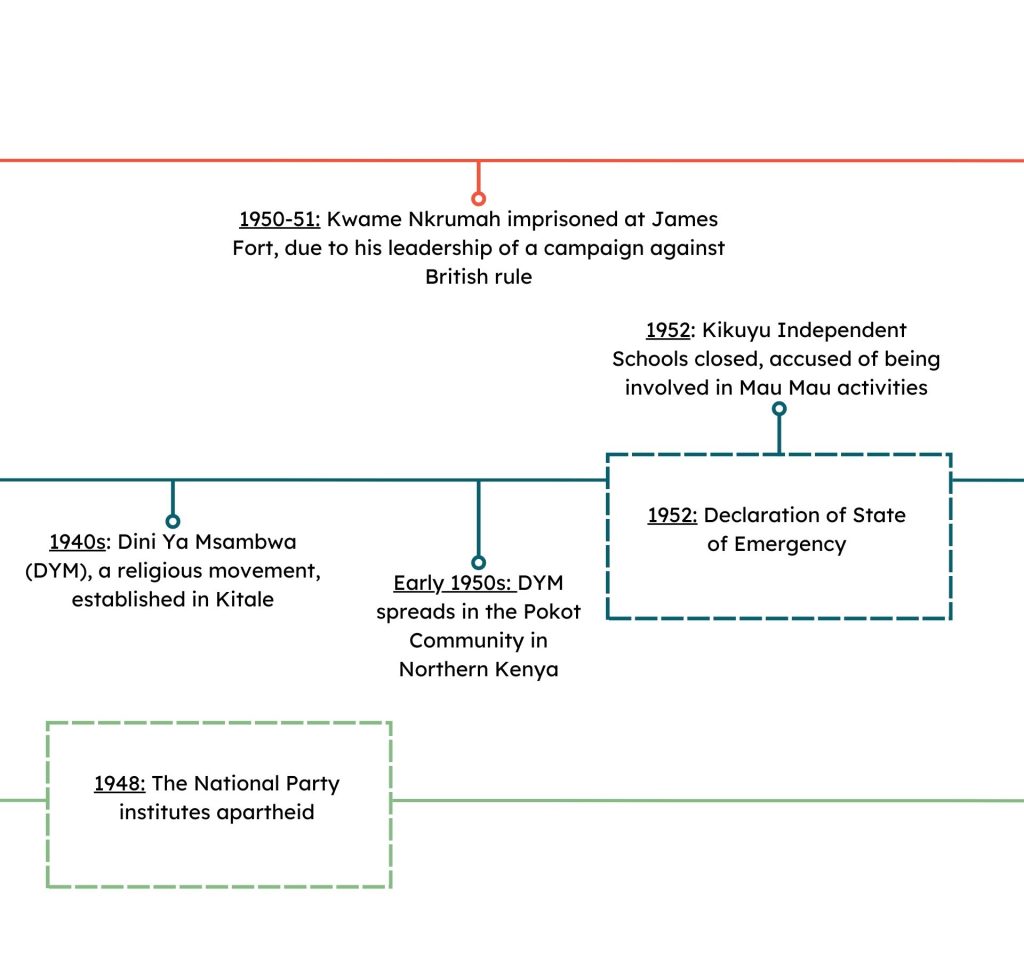

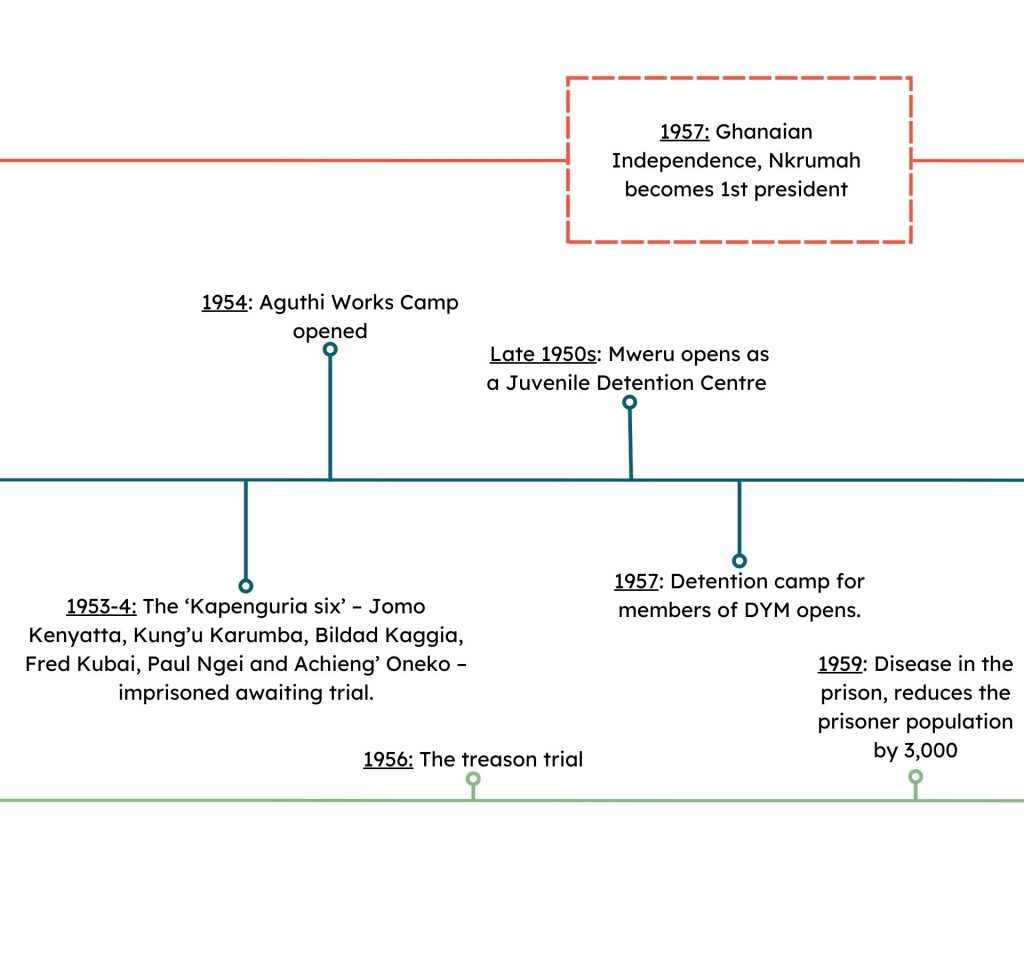

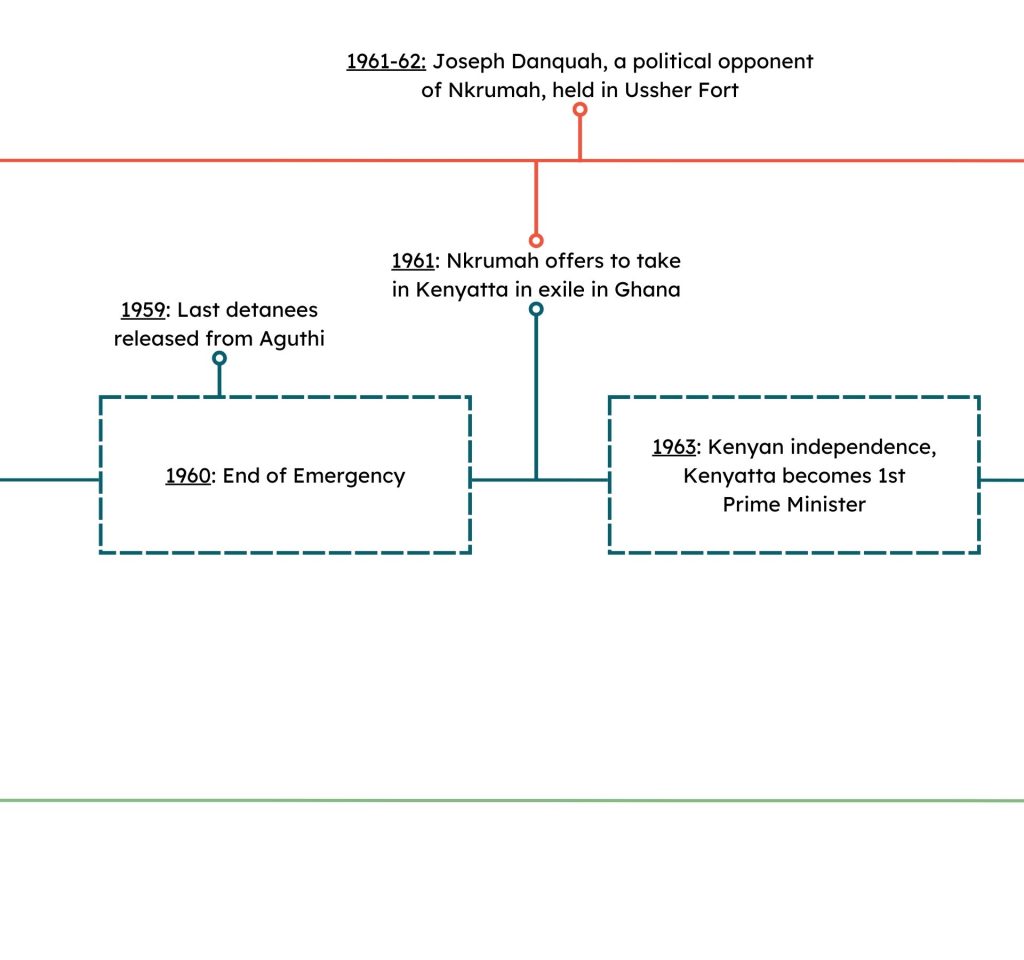

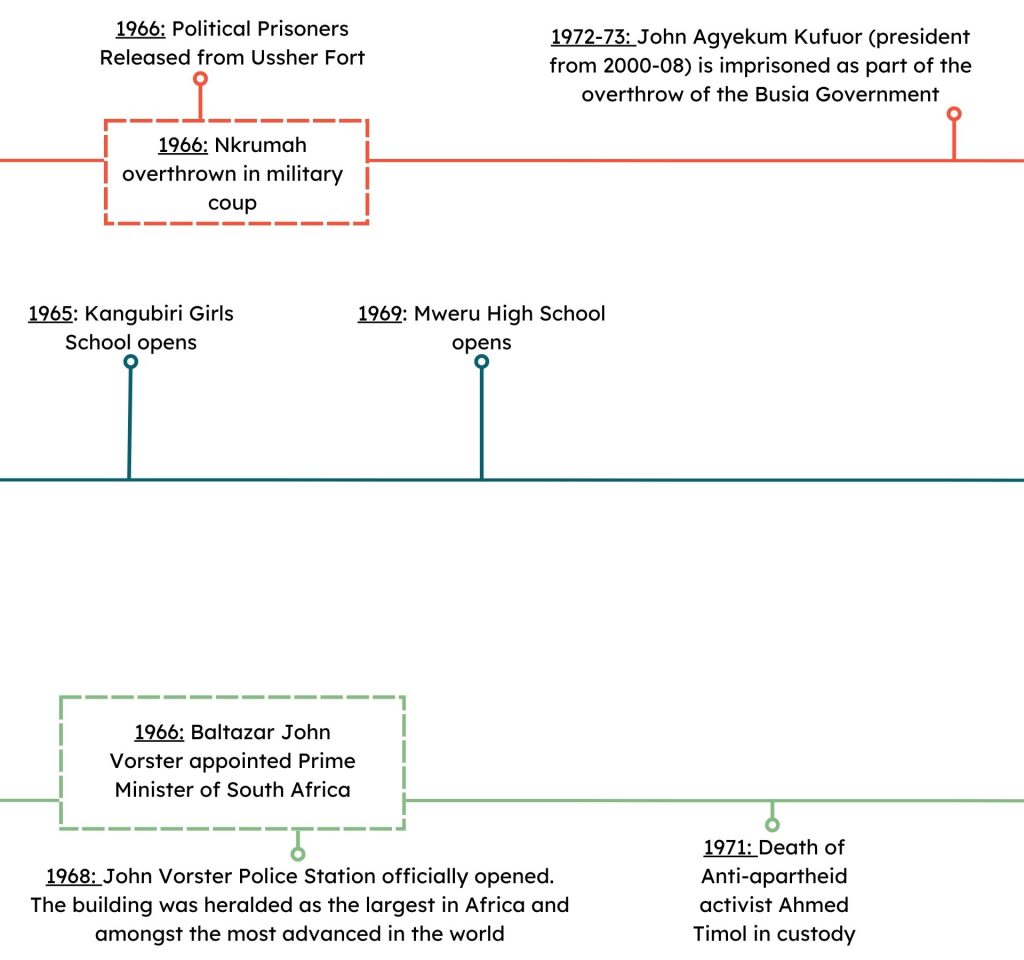

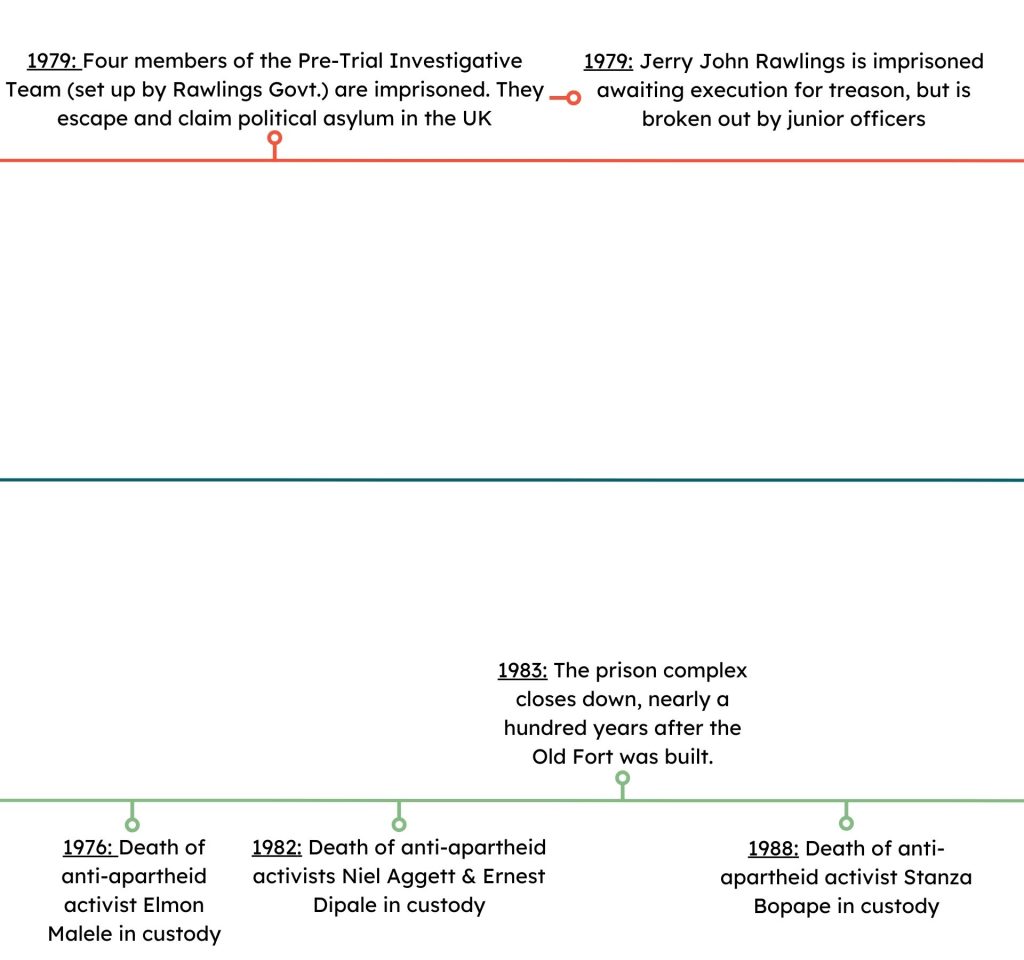

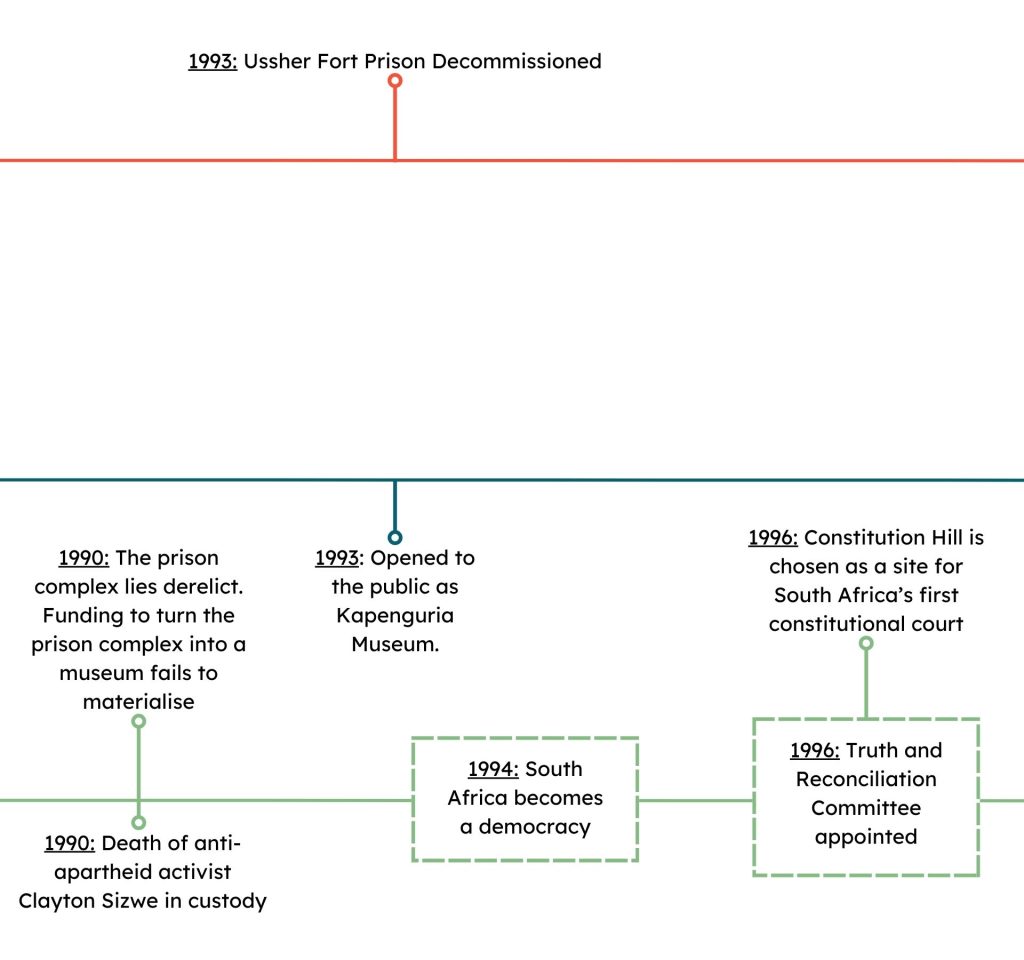

Ussher Fort and James Fort both served as prisons during colonial rule. Between 1950-51, Kwame Nkrumah was imprisoned in James Fort, due to his involvement in a campaign against British rule. Ghana gained full independence in 1957 with Nkrumah as president. Both Forts were retained as prisons, and many leaders were imprisoned at Ussher Fort over the years. Joseph Danquah, an opponent of Nkrumah, in was held in 1961-62 (he died in Nsawam Prison in 1965). John Agyekum Kufuor (president 2000-08) was imprisoned as part of the overthrown Busia Government 1972-73. In 1979, Jerry John Rawlings was imprisoned awaiting execution for treason but was broken out by junior officers. Rawlings went on to twice be the military leader of Ghana and to serve as elected president for eight years. The two forts have now been decommissioned as prisons, Ussher Fort in 1993 and James Fort in 2008.

Kenya

Aguthi & Mweru Works Camps

A large network of detention camps was set up by the British colonial government in response to anti-colonial movements in Kenya. It is widely established that the British inflicted torture on many of those detained in the camps. This period of Kenyan history 1952-1960 is often known as ‘the Emergency’, as a state of emergency was declared, which facilitated this mass incarceration and other repressive measures. Aguthi and Mweru Works Camps, in present day Nyeri County, were both final detention centres where detainees were held prior to release. At the camps, detainees were conscripted to make bricks and labour on agricultural and infrastructure projects. Aguthi was described by colonial intelligence as a ‘model’ camp, while what happened at Mweru is less well known and possibly detainees experienced harsher treatment. Civilians were also detained in colonial villages which were often located near the camps.

After independence most of the camps were decommissioned and Aguthi and Mweru Works Camps were both turned into Presbyterian Church of East Africa (PCEA) boarding schools. Aguthi became Kangubiri Girls High School and Mweru, after a period as a reform school, became Mweru High School. Former camp buildings are used by staff and students as dormitories, classrooms and stores. Barbed wire is still visible on the former cells, some bricks in the buildings are stamped with the initials of the works camp and the former boundaries can still be seen.

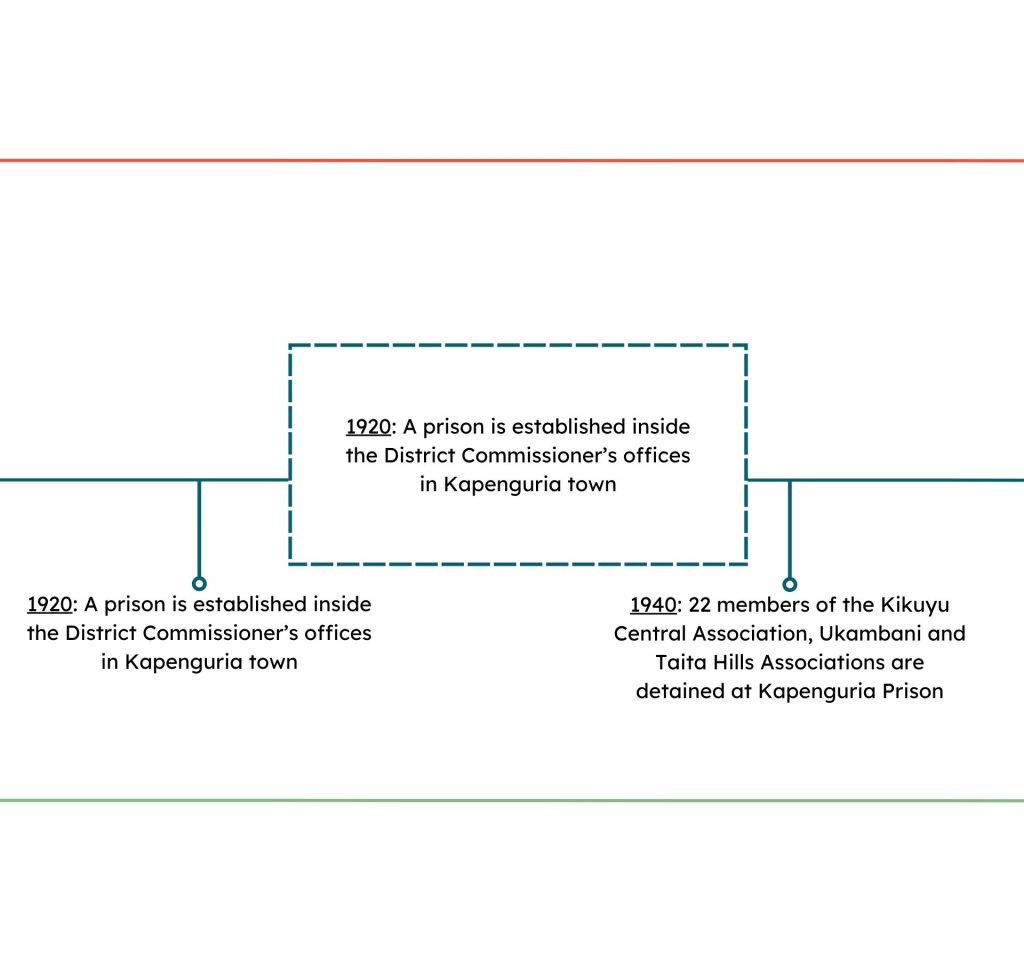

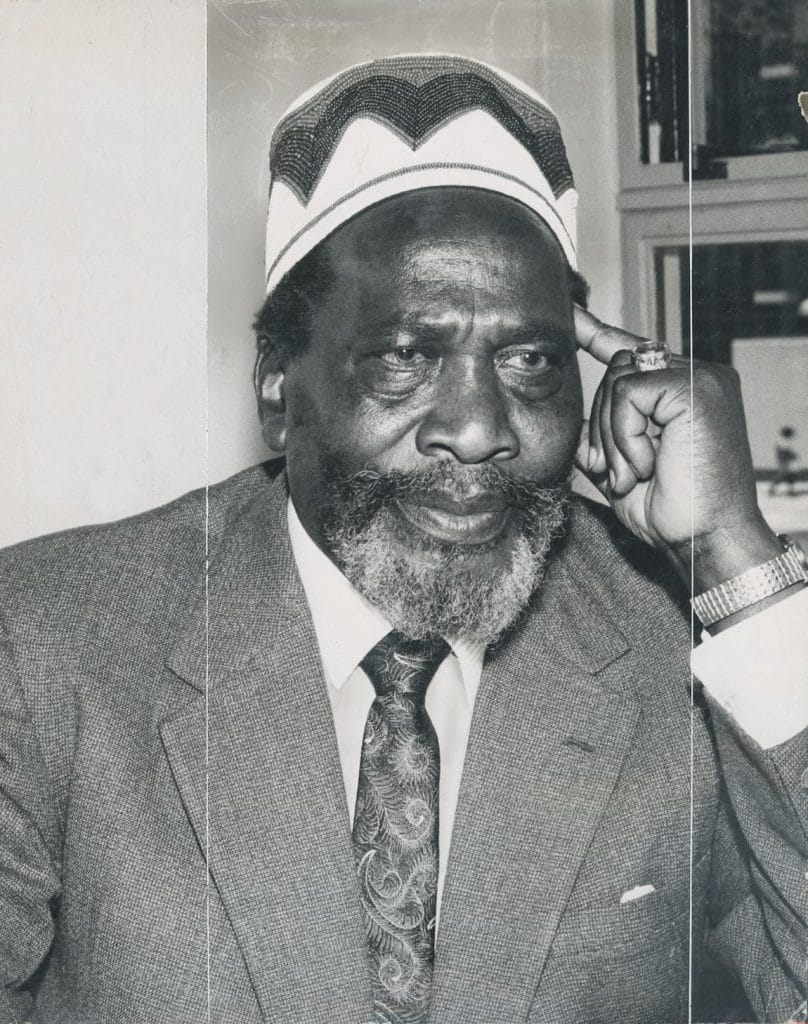

Kapenguria Prison

The Kapenguria Museum is located inside the ex-colonial prison of Kapenguria, in present day West Pokot County. Known as the ‘Kapenguria Six’, Jomo Kenyatta, first president of Kenya, and five other influential independence leaders were held and tried at Kapenguria in 1952-1953. The site has been opened to the public as a national monument since 1993. However, the Heroes’ cells were only incorporated into the museum at a later stage. The initial proposed museum was to be a celebration of Pokot culture, the cells therefore sit alongside ethnographic galleries and reconstructions of Pokot architecture and vignettes of daily life.

South Africa

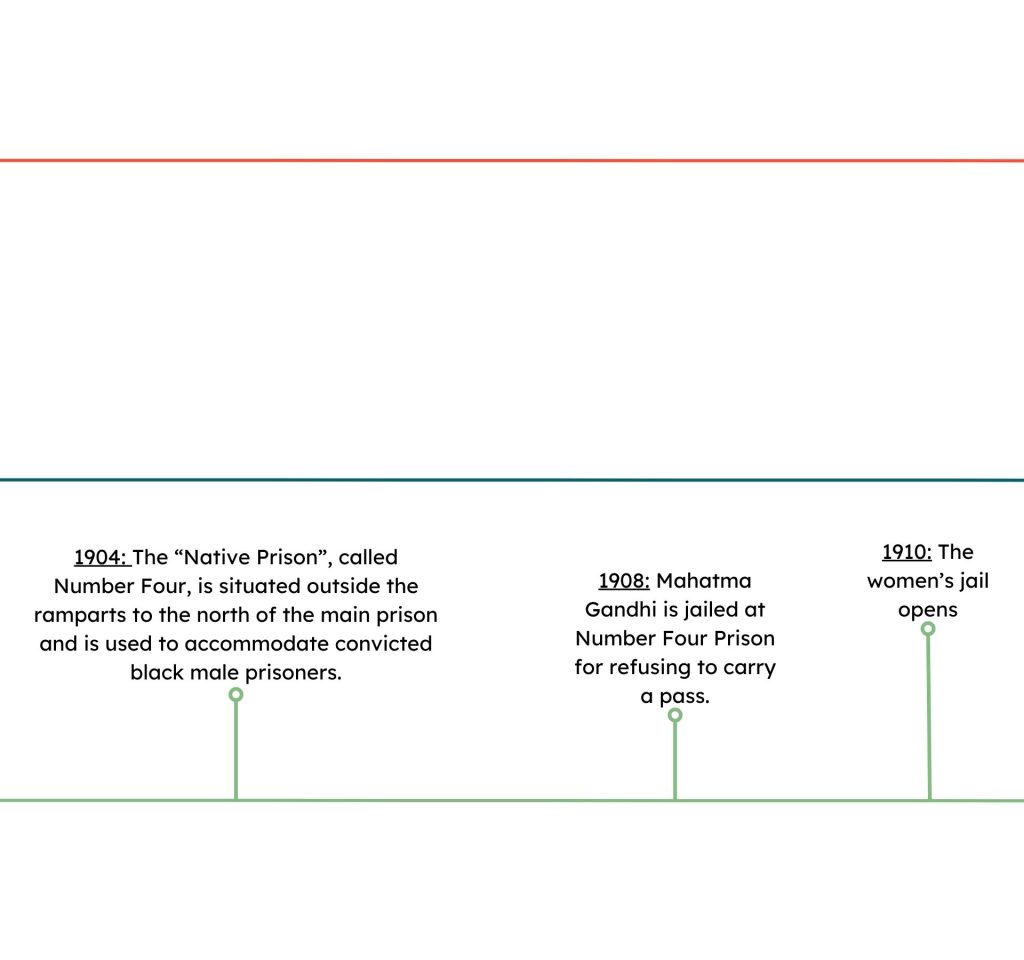

Old Fort Prison Complex

The Old Fort at Constitution Hill has a long history as a site of incarceration. During apartheid, the ‘native’ prison called Number 4 and the women’s prison in the Old Fort were sites of repeated human rights violations. Anti-apartheid campaigners such as Nelson Mandela, Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, Oliver Tambo, and Albertina Sissulu were all held at the site, alongside many less prominent anti-apartheid activists. Many others also fell foul of apartheid’s racist laws and regulations and ended up imprisoned there. Harsh detention conditions directly contributed to the deaths of many prisoners between 1948 and 1983. Since 2004, the preserved jails have formed part of a Human Rights precinct which includes the Flame of Democracy and the Constitutional Court and memorialises the sacrifices made by former inmates.

John Vorster Square Police Station

In 1968, Prime Minister Balthazar John Vorster relocated the Marshalltown Police Station to its current location and renamed it John Vorster Square Police Station. The building was characterised by its square-shaped, blue structure. The police station was heralded as a ‘state-of-the-art’ modern police station, and the largest in Africa. It housed all the major divisions of the police force, including the Special Branch dedicated to curbing anti-apartheid sentiments. Its reputation as a site for torture and brutality soon followed and the building became the primary location for detention, interrogation and imprisonment of anti-apartheid activists, a number of whom died at the station between 1970 and 1990.

In 1996, John Vorster Square was renamed Johannesburg Central Police Station. It continues to function as a highly securitised police station despite attempts by former inmates to encourage a change in function. The site has been the focus of a number of inquests into apartheid deaths in detention, many of which have concluded that detainees were unlawfully killed in custody.

Colonial Incarceration over Time

The Afterlives project has looked at seven sites in three different countries: Ghana, Kenya and South Africa. In examining these sites, the project also explores how different phases and forms of incarceration in Africa are remembered. This long history of incarceration, which extends over hundreds of years, has been tightly tied to deeply racialised, colonial forms of power. Whilst not all of these phases of incarceration took place during colonial rule, they are racialised and follow what we would call ‘colonial logics’. We therefore talk about both the trans-Atlantic slave trade and apartheid era imprisonment as colonial incarceration, in order to highlight the continuities between these even as they obviously have significant differences.

The Ghanaian sites – Ussher Fort and James Fort – are those with the earliest history of European carceral practices. Neither of these forts are major slave hubs, however, some slaves were traded at these forts by the large trading companies which owned them. Slaves also worked at the forts and settled in the area. The Alata quarter of Ga Mashie, was established by slaves and free artisans associated with James Fort. During British colonial rule, the two sites were repurposed as prisons. This history of reuse of buildings and sites, as well as the recursive (reoccurring) nature of incarceration and imprisonment is found across all our sites. In 1968, Prime Minister Balthazar John Vorster relocated the Marshalltown Police Station to its current location and renamed it John Vorster Square Police Station. The building was characterised by its square-shaped, blue structure. The police station was heralded as a ‘state-of-the-art’ modern police station, and the largest in Africa. It housed all the major divisions of the police force, including the Special Branch dedicated to curbing anti-apartheid sentiments. Its reputation as a site for torture and brutality soon followed and the building became the primary location for detention, interrogation and imprisonment of anti-apartheid activists, a number of whom died at the station between 1970 and 1990.

Incarceration has frequently been used against those challenging colonial forms of rule. And this is a story that can be seen at all the sites. In Kenya, the sole reason for the creation of Aguthi and Mweru Works Camps was to incarcerate those struggling against colonial rule. In all the project countries, key leaders of anti-colonial movements were imprisoned by colonial or apartheid governments; Nkrumah at James Fort, Kenyatta at Kapenguria, and Mandela at Number 4. Imprisonment is therefore associated with political struggle and it is these memories of struggle which are often important to people in relation to these sites.

Whilst incarceration is heavily entangled with colonial forms of rule. Imprisonment and carceral practices did not stop after these struggles against colonialism and apartheid were over. Indeed, Johannesburg Central Police Station’s cells are still very much in operation.

The first freely elected presidents of all three countries were imprisoned during their struggles for Freedom.

KWAME NKRUMAH

In 1950, Kwame Nkrumah called for a national strike in response to disagreements about

how the Gold Coast’s constitution should be written. The leaders of the strike were

arrested and Nkrumah was sentenced to three years imprisonment and detained in James

Fort. In January 1951, Nkrumah’s party, the Convention People’s Party (CCP), won a

landslide election. On 12th February 1951, Nkrumah was released from James Fort,

greeted by an enormous jubilant crowd. On release, Nkrumah was asked to form a

government and took up the role of prime-minister. At independence in 1957, he became

Ghana’s first President.

JOMO KENYATTA

In 1952, Jomo Kenyatta was charged by British colonial authorities of leading the Mau

Mau uprising against colonial rule. He was detained and tried alongside five other

nationalists, Paul Ngei, Kung’u Karumba, Achieng’ Oneko, Fred Kubai and Bildad Kaggia,

at Kapenguria. Despite scant evidence linking him directly to the Mau Mau, Kenyatta was

sentenced to seven years of hard labour and indefinite restriction thereafter. His

imprisonment galvanized Kenyan resistance and made him a symbol of the anti-colonial

movement. He went on to become Kenya’s first prime minister and president in 1963

NELSON MANDELA

In 1956, 156 people, including Nelson Mandela, were arrested and accused of treason.

Many of these activists in what became known as the ‘Treason Trial’

, where held at the

Old Fort precinct before being transferred to Pretoria. They included Oliver Tambo, Walter

Sisulu, and Joe Slovo who were held at Number 4, as well as Ruth First, and Lillian Ngoyi

who were held in the Women’s Jail. Nelson Mandela was deemed too influential on black

prisoners and was isolated at the the Old Fort prison becoming its only black prisoner at

the time. In 1994 he became South Africa’s first post-apartheid president.

Leaders of Anticolonial movements from accross the globe were frequently incarcerated.

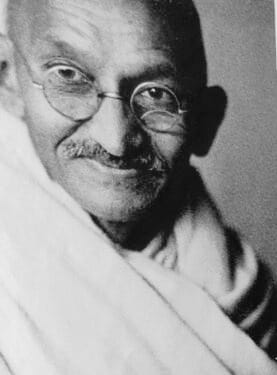

MAHATMA GHANDI

Imprisonment was a widely used strategy by the British and other colonial powers to

combat anti-colonial campaigns in Africa and beyond. The anti-colonial struggle was a tri-continental movement. Whilst opposing colonial rule in India, Mahatma Ghandi was also

interested in freedom for the people of South Africa. In 1908, Ghandi experienced the first

of his two stints at the Number 4 prison. Although he was sentenced to two months, he was

released within 19 days. The apartheid state allegedly reduced his sentence to hinder the

momentum that was gathering around the passive resistance struggle.

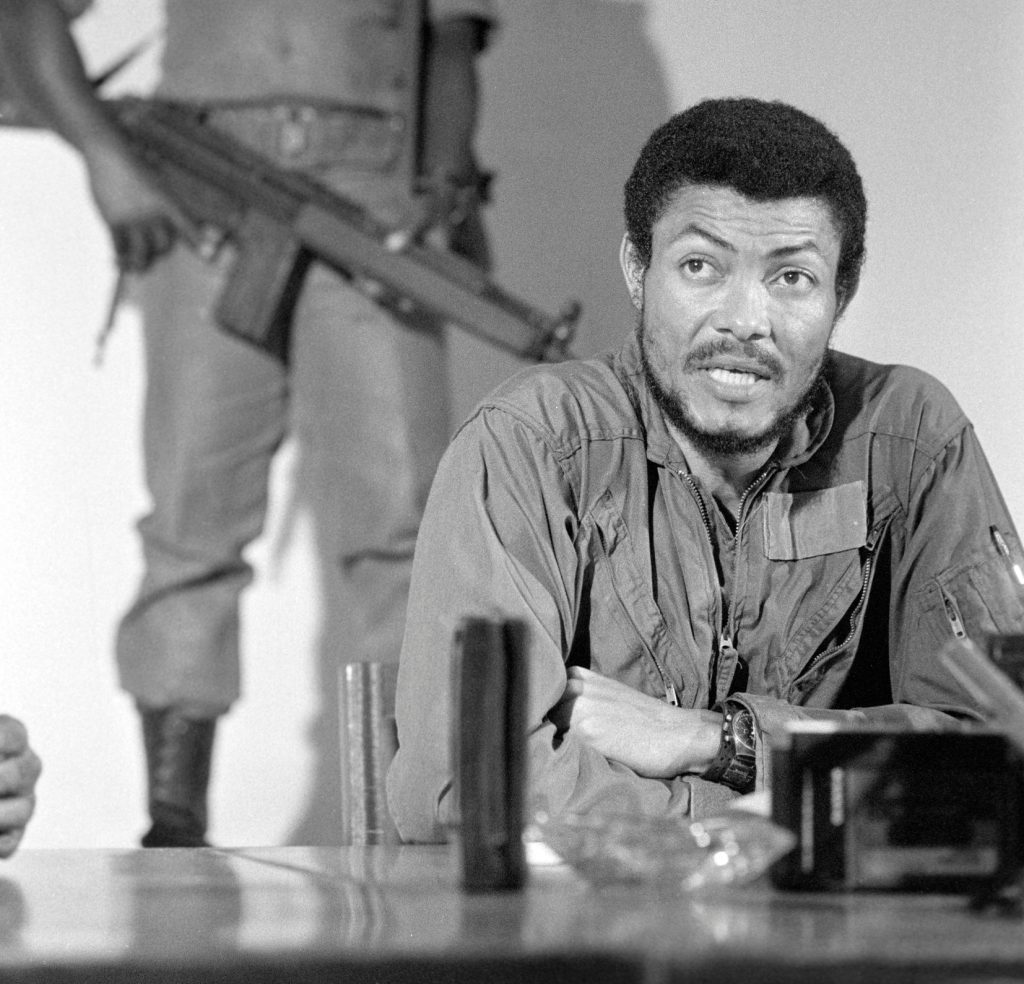

JERRY RAWLINGS

The advent of independence did not, however, end the practice of incarcerating those

perceived as political threats. In June 1979, Flight Lieutenant Jerry John Rawlings was

sentenced to death for his role in an attempted coup. But in the early hours of 4th June

1979, he was sprung from Ussher Fort by junior officers and pro-claimed Head of State.

Rawlings would only be in power for less than four months on this occasion but he would

go on to take power again as a military leader and later serve two terms as an elected

president.

Making a Mark

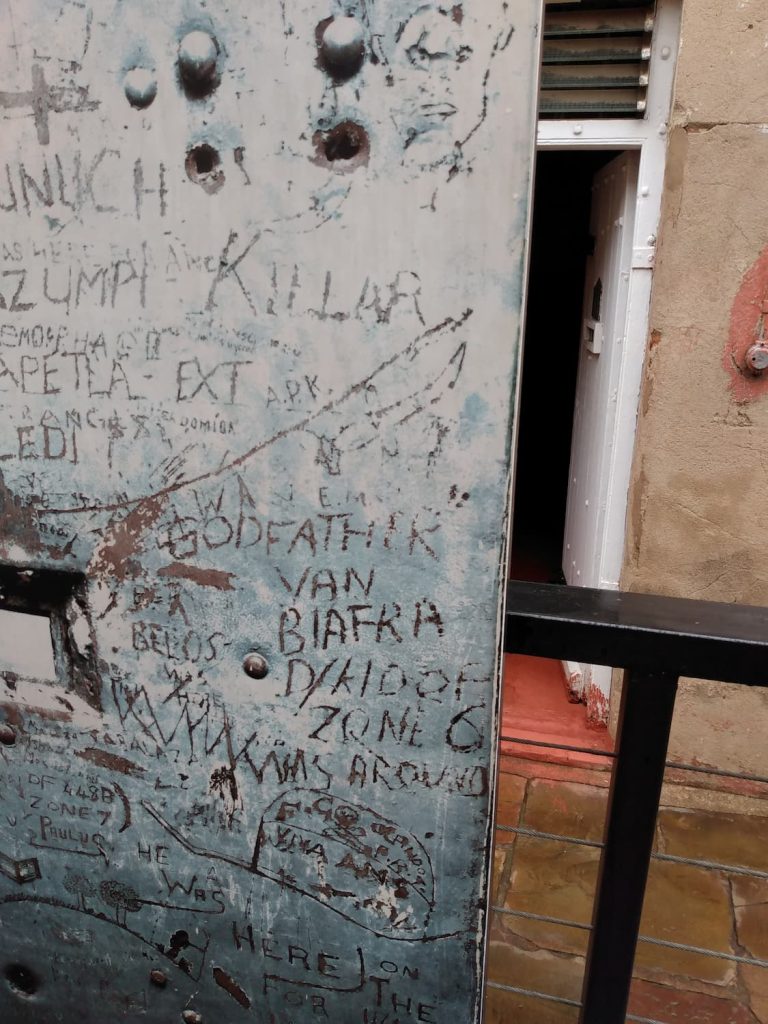

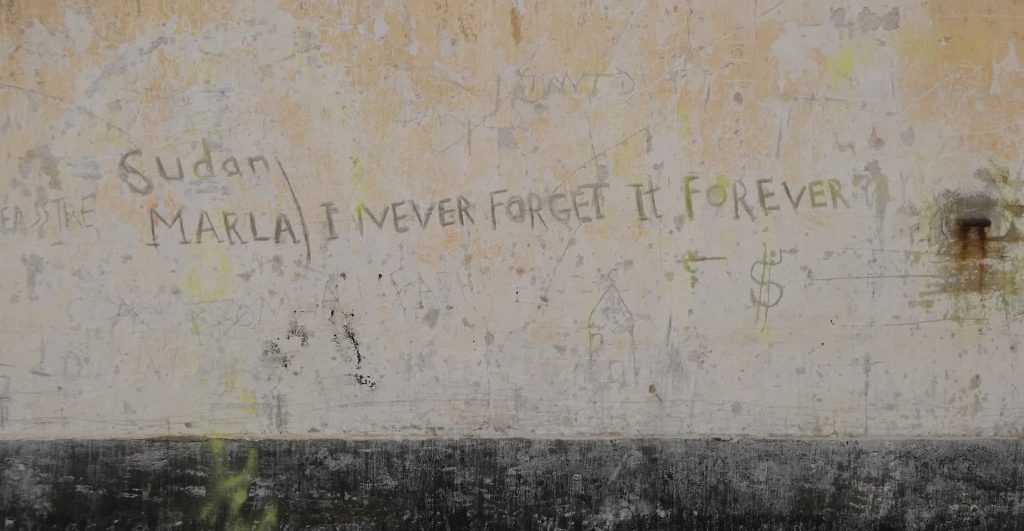

Those detained and confined in these sites have often left their mark on them.

Their writing and drawing on the walls and doors remain. Their marks are sometimes made with pencils, chalk, pens or paint. But they are also often scratched or etched into the surface, engraving them into the fabric of the buildings. Whilst there are frequently religious themes in these, others might be simple markings of individuals names, or may reference or remember events outside. Some are intricate and show great artistic skill, others are simpler. Frequently, their meaning and their age is unclear: they may have become less clear over time through wear and weather, or they may have been partially covered over by repainting or renovation, or their meaning gets lost amidst the visual noise of many such marks etched into the same surface.

International connections

Incarceration implies being cut off and separated from the wider world. Yet graffiti at both Constitution Hill and Ussher Fort show that the worlds of those that were incarcerated were often much more transnational than might be assumed. Graffiti on the back of a cell door in Number 4 at Constitution Hill references Biafra, the attempted secessionist state that tried to break away from Nigeria in the late 1960s at some 3,500 miles distant. At Ussher Fort, ‘Darfur’ is scratched into the wall, most likely by one or more of the Sudanese housed there by the Ghanaian government whilst their asylum applications were processed. Graffiti is sometimes also left by visitors and on one visit to the Old Fort in Johannesburg ‘Free Palestine’ was scrawled in marker on an otherwise recently plastered and painted wall.

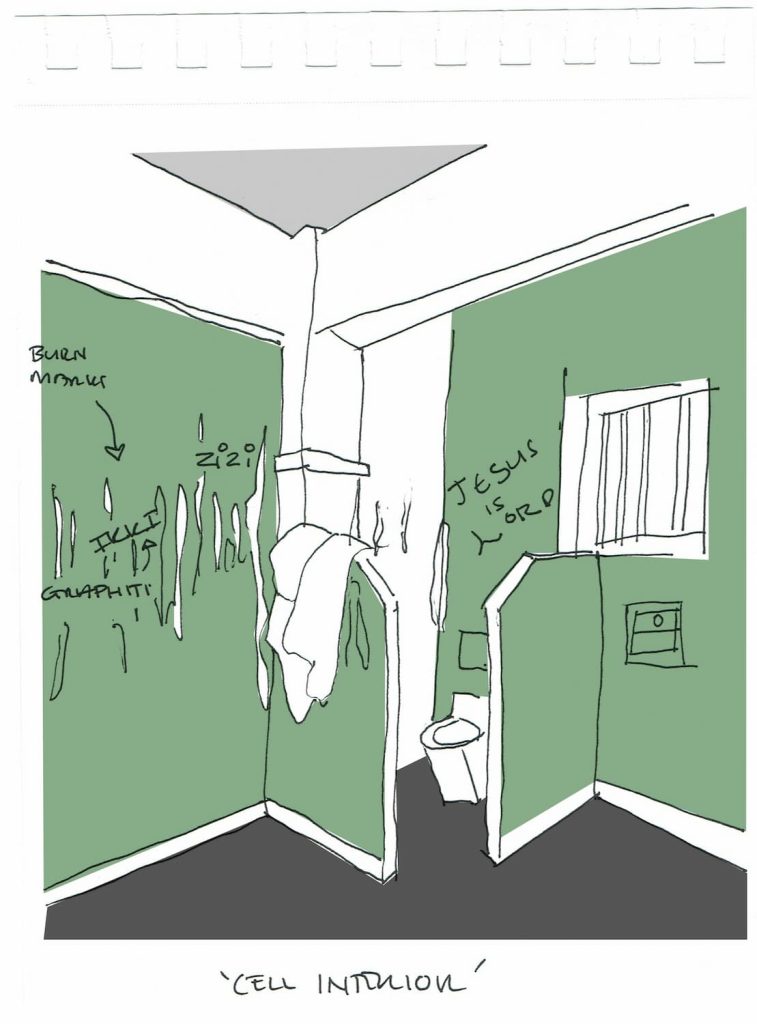

Religious Images & Affirmations

Frequently the images and writing etched onto the surfaces of these sites of confinement are religious. References to bible verses, prayers, words of praise and images of religious figures.

Calls to faith are found inscribed in the most unlikely of places. At the holding cells of the old John Vorster Square, religious affirmations are found above the toilet along with burn marks and fingernail scratches sunk into the

plastered walls.

Memory

These sites are part of many diverse stories of loss and remembrance. At Mweru High School, the wooden rafters in one classroom bear the chalk inscription ‘Masusu was a hero a Mau Mau’. The meaning is not clear. Maybe this is a reference to someone they want to remember as a hero – a family member involved in the struggle? Or maybe the idea of being a Mau Mau hero is being applied to someone else. In Ussher Fort, the meaning of the the words gouged into the wall, promising to never forget Marla, a village in Darfur, is perhaps clearer. Most likely inscribed by those seeking asylum in Ghana, a promise to remember what they have left behind, the place and the horrors of conflict.

Haunting

Ghost stories, senses of unease, the eerie and the ‘spooky’ are reported at all the sites. To us, these represent attempts to grapple with the horrors of the past that these sites were both witness to and part of. They are evidence of the ways in which these pasts haunt the present.

BONES, GHOSTS AND UNEASE

Students shared many ghost stories about their school and spoke of the sensations of ghosts lurking at night. In Mweru, boys avoid collecting wood from the tree over the memorialised torture cell. Staff at Kangubiri discussed students finding bones whilst clearing ground for planting, they blamed banana tree roots for pushing the bones to the surface. Staff reburied these remains, the area is no-longer farmed and, ‘to protect themselves’, staff avoid the place where the bones were found. Some of them also pray to calm the spirits of the people who suffered and died there.

Ghost stories, senses of unease, the eerie and the ‘spooky’ are reported at all the sites. To us, these represent attempts to grapple with the horrors of the past that these sites were both witness to and part of. They are evidence of the ways in which these pasts haunt the present.

As you ascend the final flight of stairs, in the former John Vorster Square Police Station, and enter through the security doors onto the notorious 9th and 10th Floors the atmosphere changes. Large louvres block out any daylight entering through the windows, there is very little to no foot traffic through the corridors and the space feels sanitized, as if to scrub away stains. These floors were the site of many incidents of torture and even murder during the apartheid era. Police officers who occupy those offices speak about the uneasiness they feel in working past 5 pm.

“This office behaves differently at night, something feels ‘off’. We try as much as possible not to be here then…” Police Officer working on the 10th Floor of Johannesburg Central Police Station

Part of & Apart From

Incarceration is seen to separate the incarcerated from society. Yet sites of incarceration are also embedded in the places in which they exist. The Afterlives of these sites often continues this duality with communities engaging with sites but also feeling excluded from them in various ways.

KAPENGURIA MUSEUM & KANGUBIRI AND MWERU SCHOOLS

Kapenguria Museum is located in a remote part of Kenya. This remoteness was a deliberate attempt by the colonial authorities to isolate independence leaders and, they hoped, reduce their support. The museum and the cells it contain are a gazetted (registered) monument, signifying their national importance. Although the museum houses exhibitions about Pokot life, some locals see their history as overlooked. The descendants and current representatives of the anticolonial Dini Ya Msambwa (‘religion of the ancestors’) movement are pushing for recognition of the detention of its members at Kapenguria or at the nearby camp.

As Aguthi and Mweru works camps are now boarding schools, the sites themselves are not open for visitors. So the story of these sites is not publicly told. However, staff, students, and local communities retain vivid memories (personal and/or communal) of the incarceration that took place at these sites. They recall not only the imprisonment of detainees (often family members or neighbours) in the camps, but how whole communities, men, women, children, and the elderly were incarcerated in colonial villages. Some remember these events with pride, often linked to their family’s involvement in the struggle. For others, however, memories can be ambiguous. Especially as some people fought with the British, as part of what was known as the Home Guard, and others suffered due to Mau Mau violence. Even for those who were part of the struggle, the memories can be painful and traumatic rather than jubilant.

USSHER FORT & JAMES FORT

Quite a few people living nearby Ussher Fort and James Fort have not been in either of them or have only visited when taken on a school trip. However, Usher Fort and James Fort are key landmarks for the community in Ga Mashie (James Town & Ussher Town), even for those who have never been inside. In addition, there are two key points when the community does engage more with Ussher Fort during two different kinds of festival.

The Homowo Festival is a thanksgiving festival celebrating the start of a new fishing season. The name Homowo can be literally translated as ‘hooting at hunger’. Ussher Fort plays a key role in the communal elements of this celebration for the Gbese clan. Their procession to sprinkle kpoikpoi and pour libation at key locations in their quarter includes Ussher Fort, which contains one of the graves of the founders of their community.

The Chale Wote Festival is a much more recent addition to the calendar of Ga Mashie. First held in 2011, Chale Wote is a large street art festival which takes place in the streets and venues across Ga Mashie and beyond. It was founded by artists who wanted to give new meaning to the colonial buildings that shape this part of Accra, including Ussher Fort and James Fort. The event has grown over the years and draws spectators and participants from across Ghana and the globe. Chale Wote is a key time when community members enter Ussher Fort.

CONSTITUTION HILL & JOHANNESBURG CENTRAL POLICE STATION

Constitution Hill is located at the intersection of three city precincts: Hillbrow (East), Parktown (North), and Braamfontein (West). These precincts are highly diverse and range from the extremely wealthy to the very deprived. As a result, it becomes difficult for communities on either side of the financial spectrum to fully find belonging at the site. Constitution Hill management tries to bridge this gap by hosting festivals, concerts, functions, talks, and events to encourage engagement and dialogue with the community.

Johannesburg Central Police Station is still referred to by many as John Vorster Square. The building struggles to shrug off its history of torture and abuse. The police force tries to overcome this by building relationships through engagement with community policing forums and through attempts to tackle crime in the area.

Race & Incarceration

Whilst the racial nature of incarceration practices is most obvious in South Africa due to the history of apartheid, racial thinking was central to colonial logics and therefore to colonial practices of imprisonment and incarceration across Africa and indeed the globe.

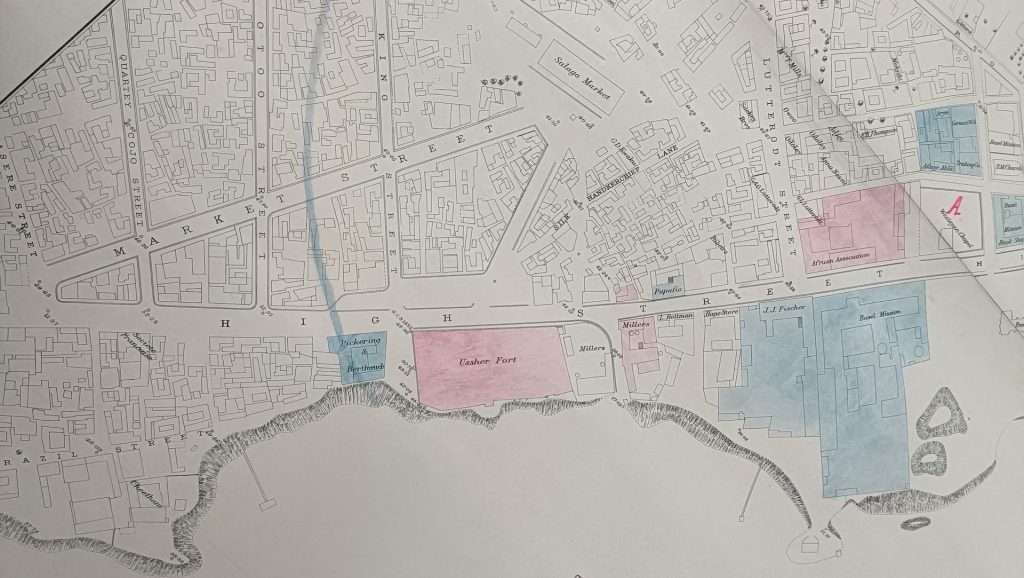

GHANA

The Accra Town Survey of July 1913 shows the streets and buildings that make up the city. Ussher Fort was at this time a working prison. The outline map has been coloured to show ‘important’ distinctions in the usage and access to different buildings. It is shaded to show what categories of people, Europeans or ‘Natives’ , are allowed within their confines and at what time of day. Ussher Fort is shaded red to show that is a place for ‘Europeans by day only, natives by night’. The prison is therefore seen to be a zone for ‘natives’ , but one governed and administered by Europeans. This repeats the racialised patterns of slavery and incarceration enacted since the fort was built.

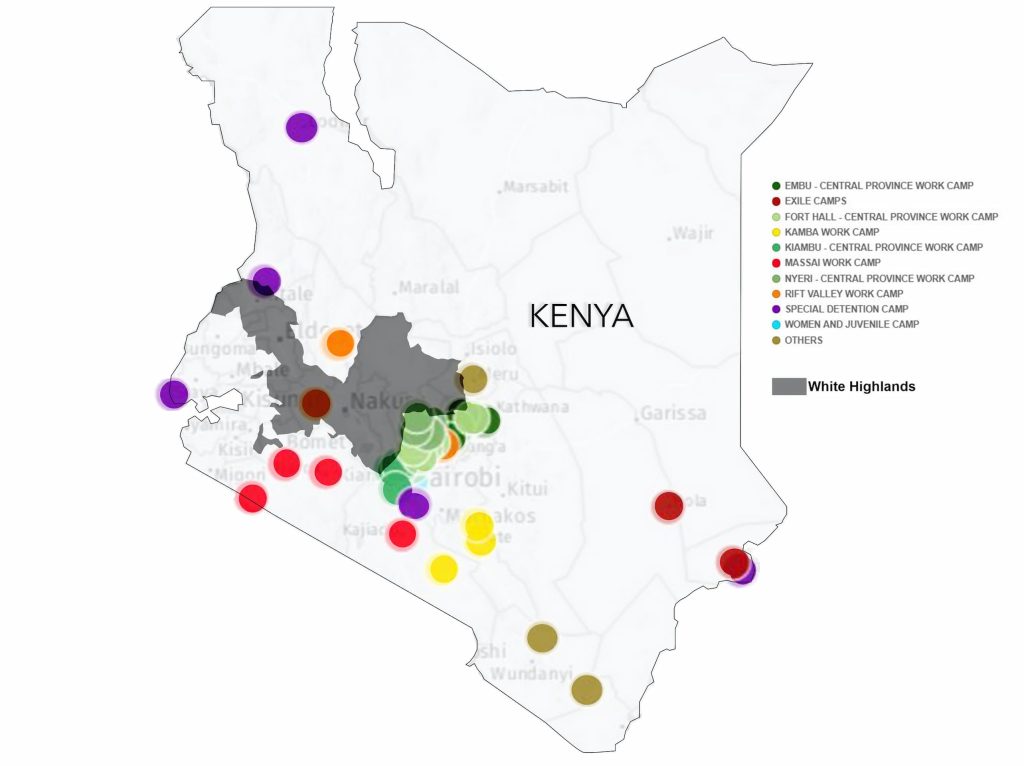

KENYA

During colonialism, many people in Kenya were systematically displaced from the most agriculturally productive areas by white settlers. The alienation of the ‘White Highlands’ around Mount Kenya led to the Kikuyu population being relegated to tenant farmers, dramatically altering their traditional land ownership and livelihoods. This displacement resulted in many Kikuyu being designated as ‘squatters’ on what they regarded as their land. Widespread dissatisfaction at this alienation from the land grew more intense following the 1937 Resident Native Labourers Ordinance, which severely restricted ‘squatters’ access to land and their ability to keep cattle. This undermined both their livelihoods and their traditional means of converting wealth into social status through livestock. These grievances were crucial in the Mau Mau uprising. The overlap of the detention camps with the ‘White Highlands’ is due to the geography of these grievances. Moreover, the detention camps were part of a broader strategy to not only suppress resistance, but to clear the land for further colonial expansion and settler occupation.

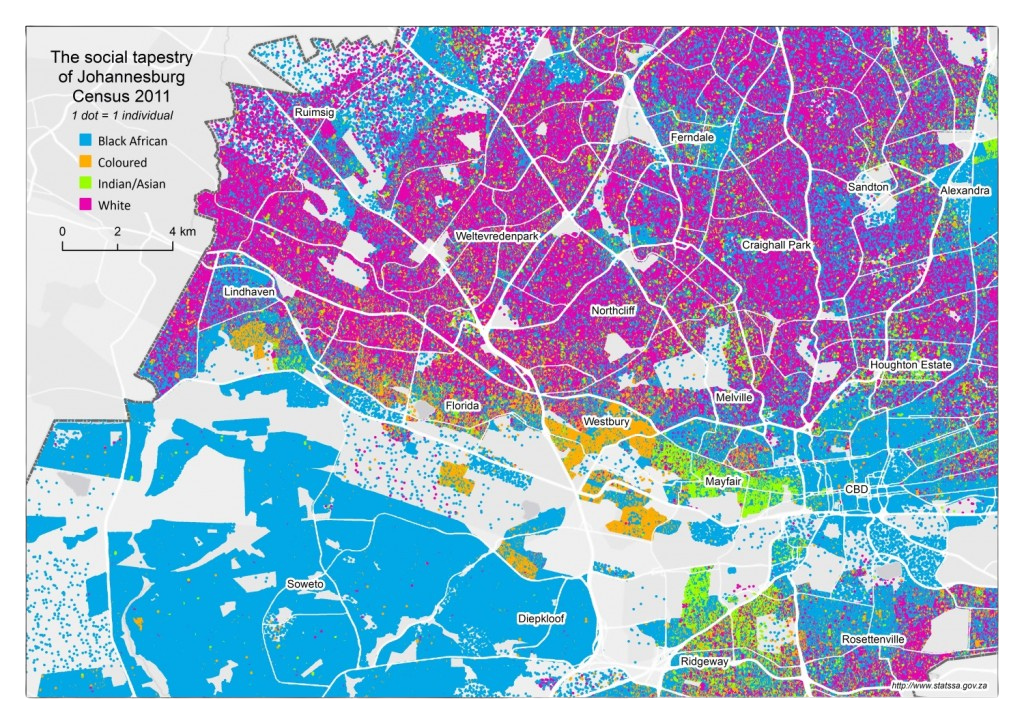

SOUTH AFRICA

The Group Areas Act of 1950 assigned racial groups to specific residential and business districts in a system of urban apartheid. In 2011, a project by Statistics South Africa, ‘Mapping Diversity: An Exploration of our Social Tapestry’ explored the long-lasting effects and the gradual untangling of racial enclaves in Johannesburg (see map). Apartheid was applied in prisons and police stations just as much as in city districts. John Vorster Police Station has entrances, cells, and designated sections for Europeans and ‘Natives’. At Constitution Hill, the Old Fort was used to incarcerate white prisoners and Number 4 and 5 prisons were built to house black prisoners. In Number 4 and 5, prisoners were held in large communal cells (rather than individual ones) which were overcrowded and rife with disease, and treatment in these sections of the prison was harsher. The racial disparities in prison in South Africa persist and non-white South Africans remain much more likely to experience imprisonment than their white compatriots.

Select a country to continue...

The Afterlives of Colonial Incarceration project is an academic research project, based at Newcastle University. Through this project we have undertaken research in Ghana, Kenya and South Africa, looking at how places that were once sites of incarceration have been repurposed. We are interested in what this repurposing tells us about the relationship between memories of slavery, colonialism and Apartheid and current political identities. We are extremely grateful to all those who contributed to this research and who helped us along the way.

Project team

WITH THANKS TO

National Museums of Kenya

Staff and Students of Kangubiri Girls High School

Staff and Students of Mweru High School

The Museum of British Colonialism

Ghana Monuments and Museums Board

Constitution Hill Johannesburg

The South African Police Service

Unless otherwise stated all photographs in the exhibition were taken by the project team.