On this day, sixty years ago, ten men were proclaimed dead in a British colonial detention camp at Hola in the Coast Province of Kenya. Three days later an eleventh man was declared dead. The British government claimed their deaths were the result of drinking contaminated water. What soon became apparent, however, is that this claim was nothing short of a government cover-up.

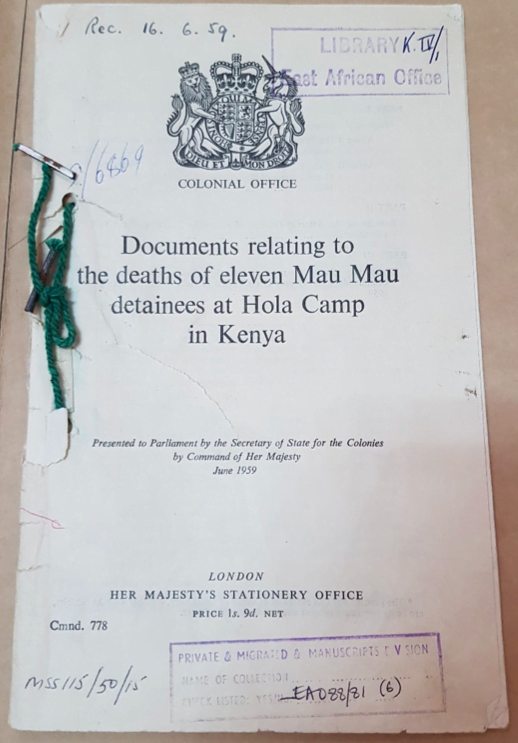

With the anniversary of this incident at Hola detention camp in mind, I spent a few days in the Kenya National Archives (KNA) this week exploring what files are housed there in reference to Hola. As the outgoing British colonial government secretly removed the main bulk of their papers referencing the period of the Mau Mau conflict, unsurprisingly there was little to find. With the kind help of the KNA archivists, however, we were able to locate a document containing the full inquiry presented by the then Secretary of State for the Colonies to the UK Parliament in June 1959. Using this document, we can begin to understand what happened on the 3rd March 1959 in Hola detention camp.

Image used with permission from the Kenya National Archives. File reference: KNA/MSS/115/50/15.

The British colonial government had established Hola detention camp to house those classified as the most ‘hard-core’ fighters of the Land and Freedom Army. Hola was one of many detention and work camps the colonial authorities established during the 1950s whereby detainees were to complete a form of ‘rehabilitation’ before they would be allowed release. Upon a visit in November 1958 by the Commissioner of Prisons to Hola, it was a decided that a new plan had to be drawn up to tackle the lack of discipline amongst detainees in this closed camp. So, what was this new plan and how did it lead to the death of eleven detainees?

After a detailed inspection of the camp, the then Acting Assistant Commissioner of Prisons Mr Cowan and the Camp Commandant Michael Sullivan drew up a plan on what action was to be adopted to force reluctant detainees to work. This plan, which became known as ‘The Cowan Plan’, was designed to compel 66 uncooperative detainees to work by clearing each of the living compounds, housing the detainees, separately and escorting them to the work site. A vital part of this plan was that any individual who refused to obey this order would be ‘manhandled to the site of work and forced to carry out the task’. With ‘manhandled’ and ‘forced’ being typically vague, an environment was created to allow legal ambiguity.

In the implementation of this plan on the 3rd March 1959, violence broke out between reluctant detainees and camp guards which resulted in the deaths of eleven detainees. What was initially insinuated through a government press handout released on the 4th March 1959, was that these individuals had drunk contaminated water. Eight days later however, it was proclaimed that they ‘may’ have died due to injuries on their bodies caused by violence. From here a full inquest was declared. The medical evidence later presented to parliament detailed each case of death ‘was found to have been caused by shock and haemorrhage due to multiple bruising caused by violence’. Not a single criminal charge was brought against any persons involved, it was argued by the Attorney General in Kenya that this was due to unreliable evidence and detainees’ refusal to cooperate as witnesses. It was, however, declared that illegal force had been used by camp guards and therefore caused fiery debate in the House of Commons.1

The team with Mr. Wambugu Nyigi in September 2018.

The incident at Hola was one of many scandals in the British colonial government’s attempts to suppress those fighting against colonial power. Mr. Wambugu Nyigi, a Hola massacre survivor was one of four Kenyan claimants who successfully sued the UK government for the use of torture during this brutal conflict. Members of our team spent time with Mr Nyigi last year learning about the horrors of that day and the impact this has had on him. With the main bulk of archival evidence on events such as Hola remaining housed in the UK National Archives, it is important we work to better our knowledge and share these stories for those unable to easily access these archival papers.

Beth Rebisz

1. David Anderson, Histories of the Hanged: Britain’s Dirty War in Kenya and the End of Empire (London, 2005), 326-327.

This blog post has used evidence from the full inquiry presented by the then Secretary of State for the Colonies to the UK Parliament in June 1959. This document can be found in a number of places; however, the author used the version housed in the Kenya National Archives (Reference: KNA/MSS/115/50/15). The main bulk of primary material related to the Hola Massacre can be found in the UK National Archives. The author felt it was important to use evidence accessible in Kenya to signpost our Kenya based readers to material they can more easily access if desired.