This summer, the Black Lives Matter movement called for action. Many museums responded with public statements. The British Museum’s Director, Hartwig Fischer, wrote in a blogpost, ‘I hope that we will find the right ways to allow the Museum to better reflect our societies and our complex, contentious and blended histories, and become more than ever a theatre of human connection.’ Beyond this perplexing sentence, has any real progress been made?

The British Museum reopened this summer with a new ‘Collecting and Empire’ trail. Individual display panels have been placed alongside 15 objects to provide information about each object’s provenance and the historical context in which it was collected.

Unfortunately, but perhaps not surprisingly, the trail is more concerned with defending the museum as an institution than presenting a truthful representation of British colonialism and the museum’s close relationship with it. In its representation of British colonialism, the language deployed is just as strategic and risk-averse as Fischer’s blogpost.

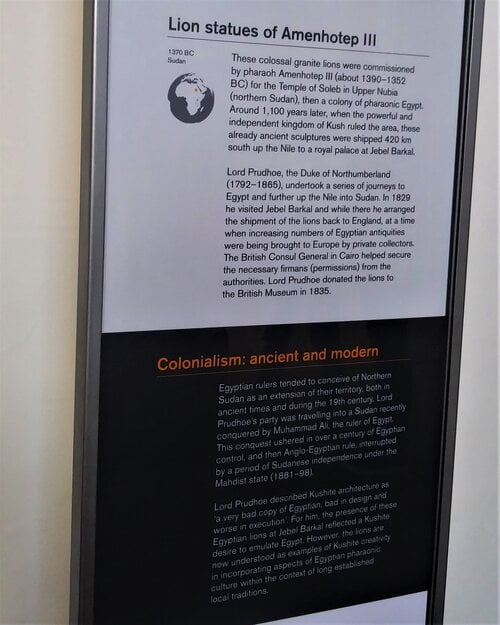

For example, a panel contextualises statues of lions commissioned by pharaoh Amenhotep III for the Temple of Soleb in Upper Nubia, highlighting that the region was ‘then a colony of pharaonic Egypt.’ While this is a historical fact, its inclusion here strategically frames visitors’ understanding of the British Empire in the region – yes, Britain colonised Sudan, but this was nothing new, nothing unique. Does the fact that Sudan was part of the empire of ancient Egypt really have any bearing on its experience of British colonialism?

This focus on the connection between ancient and modern means that the panel avoids confronting the history of British colonialism in Sudan. We read about the collecting practices of an individual – the Duke of Northumberland – and learn that Northern Sudan was under ‘Anglo-Egyptian rule’ in the nineteenth century. This is the only reference to the fact that Sudan was colonised by Britain, and it is a misleading one.

In 1882, Egypt was invaded by Britain and placed under a military occupation that would last until 1922. Throughout the occupation, Egypt was never formally a colony. Instead, a fiction of Egyptian independence was maintained. Rather than being under ‘Anglo-Egyptian rule’, Sudan was under Britain’s control. To suggest otherwise is to perpetuate a colonial myth.

The panel refers to the fact that Sudan was temporarily independent from ‘Anglo-Egyptian rule’ between 1881 and 1898. What it fails to mention is that this independence was brought to an end through a brutally violent British re-conquest. On 2nd September 1898, the British military expedition destroyed the Mahdist capital of Omdurman, killing over 10,000 people. Forty-seven British forces were killed.

Rather than reflecting ‘complex, contentious and blended histories’, this exhibition specifically marginalises those aspects of Britain’s colonial past that need to be represented and acknowledged. This risks representing British colonialism as an abstract and morally neutral phenomenon. In light of this, does this exhibition do more harm than good?

The momentum of this summer risks being lost by exhibitions such as this. The fact that the government is actively discouraging museums from productively engaging with contested heritage doesn’t help matters. This summer museums pledged to embed meaningful change. This exhibition shows that much more work needs to be done.