This excerpt is part of a full piece written by Sinem Aydınlı, a volunteer with MBC through the beraberce Xchange Program in November 2019. Sinem was a great help to the Museum, especially in preparing for our first exhibition and two-day event in London, Changing the Narrative. Sinem wrote a piece on her time with us for beraberce, which is available to read in full on their website here.

My last trip to London, almost three years ago, in 2017, was born from a kind of necessity. Thanks to certain “obscure” reasons I had not been “allowed” to complete my dissertation in Turkey, which had been classed as politically sensitive. I had been given a place to enjoy the academic freedom to finish my dissertation at Loughborough University London in the UK. In other words, one of the most powerful founding partners of modern colonial history, Great Britain, had turned into a place of “salvation”, or at least somewhere that I could express myself freely. When I came back to London for a month in November 2019 it was as a participant of beraberce Xchange Program: Sites of Memory, and I already was in the city where the colonial administration’s head office was located in 1950s, not in a place of salvation.

As an online platform founded by Kenyan and British women in January 2018, the Museum of British Colonialism (MBC) created a counter-memory from another geography and made it a part of my consciousness. In London of 2019, I started a journey into the 1950s Africa.

The team behind the “Museum of British Colonialism”, or MBC, describe themselves as “Heritage Activists” at www.museumofbritishcolonialism.org where they gather, share, and comment on material and resources related to British colonialism. MBC aims to point the gaps in colonial narratives based on the official history and to create a digital memory site where British colonialism is defined beyond the official discourse. MBC’s aim “is to provide a space – digital, physical, emotional and psychological – for people to confront, consider, assess and understand [the UK’s] less than glorious imperial past and help forge a better future”

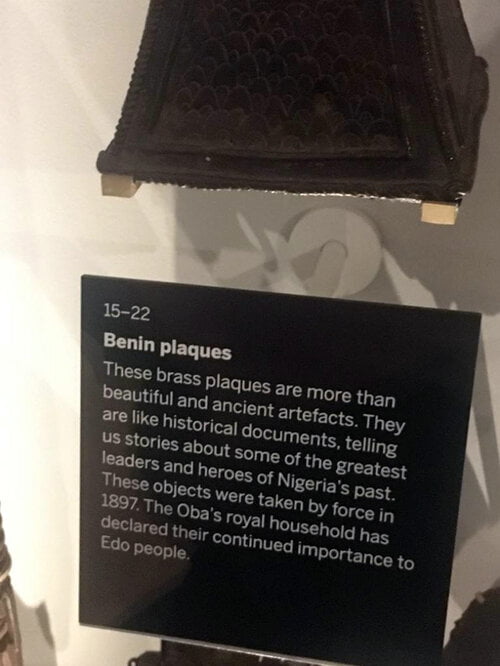

The Museum of British Colonialism is not a physical memory site, but in fact there does exist a museum in London that fully meet the meaning of such a name: The British Museum. This museum contains many colonial materials in its various collections that were taken by force, and exhibits colonial history through these materials, yet without explaining how these materials got to London (which is in line with the historical denial and contextual forgetting strategies). The museum’s collections, of course, include Africa, in collections exhibited two floors below ground.

Materials exhibited as part of the British Museum’s African Collection

Another London museum with an African collection is the Horniman Museum. If such an adjective counts when describing a museum, I can say that Horniman is a more honest museum than the British Museum. Its curators and the anthropologists who contributed to it are more critical in their explanations of how the materials exhibited arrived there from colonial countries. Although no description of any piece exhibited at the British Museum says “it was forcibly taken”, there are examples in the Horniman which do. At least they don’t reconstruct the official and so natural colonial narrative.

“These objects were taken by force in 1897” Horniman Museum

British Colonial Rule in Africa

In 1895, the United Kingdom declared rule over what it named the East Africa Protectorate. The Kenya-Uganda railway, a symbol of colonial domination and imperial success, was completed by 1901. A year later, in 1902, the white settlers, who they were actively encouraged by government policy and its apparatus (such as media), came to this area to occupy the fertile land from the Kenya’s Central highlands where the Kenya’s largest ethnic group, the Kikuyus have been living. Not so much as five years after this invasion began, in 1907, they also occupied place in Kenya’s Legislative Council. In 1920, the East African Protectorate became the colony of Kenya.

Mau Mau Struggle: Ithaka na wiyathi [Land and Freedom]

The world thought that these Mau Maus were dancing as they cut the head of the British, chopping their flesh, and drinking their blood at the evil rituals

Kikuyus formed the Young Kikuyu Association in 1920 and and Kenya Central Association in 1926 to express their land claims. In 1939, Kenyans were called upon to support the British war effort during World War Two (WW2). Indigenous Kenyans, thought they would own land in return, volunteered and participate in the war. However, their land claim did not materialise.

In 1944, Kenya African Union (KAU) was also founded, which was established to achieve independence, whose leader from 1947 was the future first president of Kenya. The majority of the Legislative Council was made up of white representatives, with a number of black African nominees who were appointed without election. Throughout 1950s, a general strike began in Nairobi by workers protesting against losing their land. The KAU was banned as part of the wartime controls on African political activities. The colonial government’s rule led the Kenyans to an economically unequal position. Kikuyus through KCA thus met with white landowners to discuss their land claims as they were engaged in farming and agriculture, and they were most exposed to the land policy of colonial rule. However, the talks ended without agreement and the Kikuyus took an oath of “land and freedom” against the misery and poverty they were experiencing. Mau Mau activists, mostly made up of Kikuyus and having a major role in Kenya’s ultimate independence, engaged in armed struggle, settling in the forest to take back the land that the “white man” had stolen from them. This was how the anti-colonial Mau Mau freedom struggle against the (white) settlers began.

Government pronounced this struggle illegal and “Mau Mau organisation” as “terror organisation” in August 1950. Disguised as policemen, members of the Mau Mau killed senior Chief Waruhiu, whom the colonial administration considers to be the “tower of power”, on the 9th October of that year. Following this event, the colonial governor appointed by the British Government declared a state of emergency on 20/21 October 1952, lasting eight years through which full of mass detention, ill-treatment, torture, violence and arbitrary murders would have taken place.

Historians refer to the “dirty war” of this period, in which colonial rule in Kenya divided the Kenyans into two: the loyalist Kikuyu (who were always on the front line) fighting in the name of the British government, and the Mau Maus, although many had come back from WW2, many lacked any military education and fought for land and freedom. During the war an estimated 70,000 Mau Mau supporters were said to have been held in detention centres (Anderson 2005). The release of inmates revealed these centres to be places of ill-treatment and torture, due to the colonial administration’s policy of continued detention of any fighter who did not confess their adherence to the Mau Mau oath. This enabled a system in which the administration could interrogate (screen) all detainees and make them confess to Mau Mau affiliation. These people were held without trial since the state of emergency still held. The MBC digitally mapped and reconstructed these detention centres in 3D as its first works for “remembering”. Each one is a piece of evidence that helps us face up to a difficult past.

Kenya gained independence in 1963, three years after the emergency ends, and official records indicate that 12,000 Mau Mau members had been killed, with the actual number estimated to be more than 20,000 (Anderson 2005). It is no exaggeration to say that the Kikuyus were trying to be destroyed in the history scene: in 1953 the Kikuyus were 46% of the population, while in 1959 the Embu and Meru together made up 28% of the population.

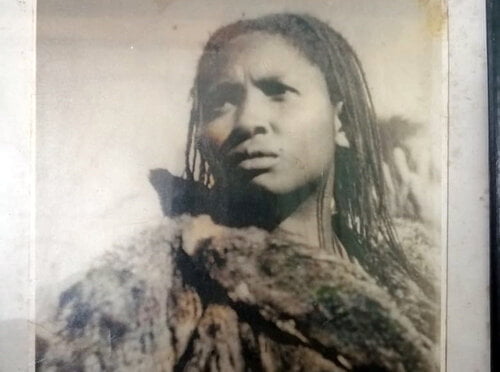

The MBC team is dispersed between Kenya and the UK and often meet physically. Thanks to the WhatsApp group they established in accordance with MBC’s digital museology approach the whole team can reach each other at any time, anywhere. On 12 December, Kenyan Independence Day, they shared a picture on the WhatsApp group to celebrate the day. The picture shows Muthoni wa Kirima, born in 1931, a relative of Susan, one of the Kenyan teammates whose testimony I read and whose story I read in the MBC’s field diaries.

Muthoni wa Kirima during the Mau Mau Uprising

Muthoni wa Kirima on Jamhuri Day, 2019

Muthoni wa Kirima Mau is one of the survivors. She was one of the most senior commanders (Dedan Kimathi, Baimungi Marete and Musa Mwariama) of the Mau Mau land and freedom movement. After Kenya gained independence in 1963, Muthoni left the forest and returned to her settlement. I think the struggle of Muthoni wa Kirima is also very important for Mau Mau women who experienced both racism and sexism. In a narrative where African women are categorized as intellectually weak and easily manipulated, Muthoni’s struggle can also be interpreted as the struggle for women’s freedom (Elkins 2005: 2014).