Our latest ‘Paper Trails’ interview responds to our statement on Palestine and commitment to creating and sharing more content on Palestinian history, especially with regards to the British Mandate period.

MBC volunteer Emily Beswick interviewed Anne Caldwell, a PhD candidate at the University of Kent. Anne studies British media representations of Zionist agriculture in Palestine. We discussed her positionality as a Jewish academic, British colonial attitudes to Palestine and Zionism, and how studying the history of British Mandatory Palestine enriches our understanding of the current Israeli occupation.

MBC: Hello! Thanks for agreeing to chat with us on such a sunny afternoon. Could you tell us briefly what your research is on?

Anne: I look at how Zionist [1] citriculture – orange-growing – was presented to the British public through different forms of cultural media, in the early 20th century. Not just the media (like newspapers), but all forms of cultural media, like art and travel guides, maps, consumer goods, and advertising.

A 1929 poster depicting Jaffa oranges, designed by Frank Newbould for the Empire Marketing Board. Image credit: The Palestine Poster Project Archives.

In our previous interviews, we were interested in how your background might shape your work. Were there any personal experiences that informed the topic that you chose?

A lot of my background informs my research. My mother’s family are Russian Ashkenazi Jews – that is, from Eastern Europe, Yiddish-speaking Jewry. They fled the pogroms that occurred at the end of the First World War, and I study and use that in my research, talking about how these particular pogroms impacted Jewish settlement in Palestine.

My mother’s family was fairly Zionist and I was raised to believe that Zionism was part of our Jewishness. I was raised in this Zionist environment on that side of my family, but my dad’s side was a bit more mixed. My grandmother was Irish Catholic, and we had a lot of discussions about the IRA growing up. I remember having conversations about what the place of violence was in anti-colonial struggles.

“ Settler colonialism was something I saw.”

It wasn’t just my dad and my grandmother having these discussions with me which made me question Israel, and in particular, question Zionism. I was partially raised in Scottsdale, Arizona, which is divided between an affluent white suburb, and – on the other side of this wire fence – the [indigenous] Salt River Pima-Maricopa Community.

So I wasn’t just hearing stories about the importance of Zionism for Jews, but I was also seeing the realities of what colonialism was and hearing family stories about the violence that colonialism entails. It really made me think about what colonialism was to real people, and the impact it had on their lives. Settler colonialism was something I saw.

That was so fascinating, thank you for sharing your personal story.

Why did you decide to focus on British media representations, what about them interested you?

From the very beginning, I was more interested in the British perspective. I know as an American that seems weird! In the US there is less of this divide about Zionism – there are anti-BDS laws in some states that prevent companies, organizations (including universities) and individuals from speaking out about or boycotting the occupation. But in the UK you’re allowed to have opinions that are critical of Zionism, even if there are similar laws being considered here. There are a lot of British historians here who study Zionism as well. That kind of freedom I’ve found really fascinating, and I wanted to know a bit more about what British media actually said.

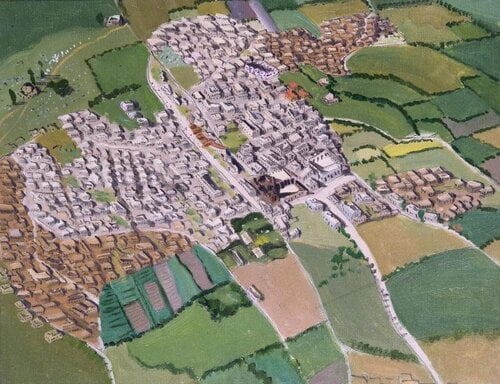

‘Gaza Seen From the Air’ by British War artist Richard Carline, 1919. Image credit: IWM

But the more relevant thing is that Zionism really relied on British support during this time. It was so important that the British support their cause. There were a lot of Zionists within the British government, and Christian Zionism had a fairly strong hold in British culture.

What do you mean by Christian Zionism?

In certain Christian beliefs, there is this idea that the Second Coming will happen if all the Jews return to Israel. And/or that if Jews return to Palestine, this will lead to revitalisation of the Holy Land to its biblical glory. It’s a belief mostly held by Evangelical Christians. Not everyone who supported Zionism, or even who came into contact with Palestine, was necessarily a Christian Zionist or Christian, but there was nearly always a biblical influence on how people perceived Palestine.

And when you looked at these newspapers and other types of media, what did you find about British attitudes towards Palestine?

Interestingly, the attitude towards agriculture was fairly universal. There was a consistent belief that the indigenous population didn’t know what they were doing, when it came to agriculture. Starting in the early 19th century, you see this belief that the indigenous population in Africa, Asia or in the Americas didn’t know and that the people coming in knew better.

You actually see a lot of the same people who were colonial administrators in India brought over to Palestine. There’s other connections across colonies too. I believe in Kenya the indigenous population wasn’t allowed to grow coffee, and while that didn’t happen in Palestine, the British administration did focus on Zionist citriculture even though most orange-growers were Arab. For example, at the end of the 1920s, orange-growers were trying to get a reduction on import tax. The British government talked to Zionist organisations and cooperatives, but when the Arab cooperatives attempted to have those same meetings, I found one letter which essentially said “They should send a letter but I’m not meeting with them.” It shows you the British colonial mentality on Palestine.

“Zionism really relied on British support during this time. There were a lot of Zionists within the British government, and Christian Zionism had a fairly strong hold in British culture.”

What about British attitudes to Zionism?

There was a huge mix. Some Conservatives supported Zionism as a way of preventing Jewish refugees who were fleeing persecution coming into the UK. There were also conservative outlets, like the Daily Mail, who subscribed to anti-Semitic conspiracy theories about Jews controlling the world. And there were people who didn’t want British government funding to be spent in Palestine.

More liberal and left media also had a mixed reaction, although there was a lot of support for Zionism. The Guardian for instance was very pro-Zionist at the time, which often surprises people. These mentalities were not necessarily what you might assume based on today’s politics.

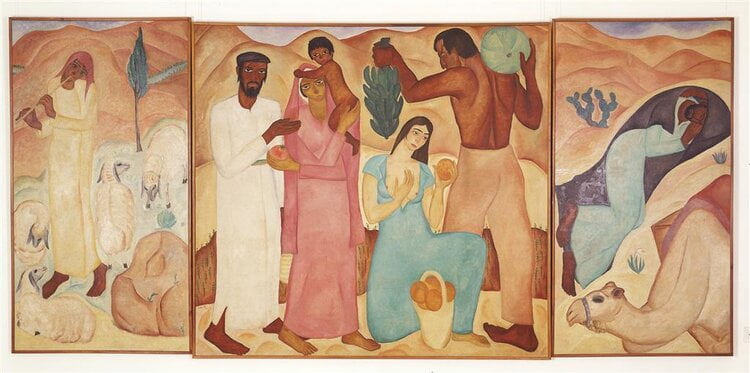

‘First Fruits’ (1923), by Israeli settler artist Reuven Rubin. The central panel shows a Yemeni Jewish family (left) and Ashkenazi Jewish settlers (right) – the idealised settlers hold the fruits of their labour, including Jaffa oranges! The side panels depict Arab Palestinians as not actively engaged with the empty land.

Image credit: The Israel Museum

Did studying the history of British Mandatory Palestine shift any of your understandings of the Israeli occupation of Palestine?

Actually, my personal understanding was far more impacted by my undergrad thesis on Zionist mentalities towards Palestinians (from between 1890 to 1948). I finished my thesis in the winter of 2008-2009, at the same time as Operation ‘Cast Lead’ [2]. I remember watching an interview with [Israeli Foreign Minister at the time] Tzipi Livni, who had this quote where she basically said that one Israeli life is worth a thousand Palestinian lives.

“People like to both-sides it, but it doesn’t feel like two sides when you’re studying Mandatory Palestine.”

So even though my research was on Zionist mentalities in an earlier period, my conclusion was that this attitude really hasn’t changed. Zionism was never a monolith, but a more extreme viewpoint took centre stage after about 1935 and pushed the narrative to the right. It wasn’t necessarily as extreme in the 1920s. That shifted my political perspective quite a lot from being a more liberal Zionist to not a Zionist at all.

Would you say looking at the history of the British Mandate in Palestine complicates the argument that Israel/Palestine is primarily a ‘conflict’ of religions…

People like to both-sides it, but it doesn’t feel like two sides when you’re studying Mandatory Palestine. The British have a habit of promoting settler colonialism, or promoting one side over another in the lands they control, and they very much did that in Palestine. The Balfour Declaration of 1917 said the British government supported a Jewish national home and was prepared to help the Zionists create a Jewish national home in Palestine.

If you really think what that means – this is a foreign power agreeing to help a European nationalist movement go into Palestine and set up a national home. These two foreign agencies are basically laying claim on Palestine and saying to its inhabitants that it’s going to be someone else’s home now. You can’t ‘both sides’ that.

“It’s important that people understand the ramifications of the Balfour Declaration and British colonialism in Palestine, to better understand Israeli settler colonialism.”

Do you see your work as relevant to contemporary discussions around both British colonialism and Israeli settler colonialism?

I think the general public, as well as academics, need to understand media a lot better and the way that culture influences us. A lot of beliefs we hold are decades or a century in the making. People talk about 73 years that Palestine has been occupied, but when you really think about it, this started before 1948. When the British came in and set up a military occupation in 1917 – that’s far more of a starting point. You start to see things really changing in the Middle East at the time, in Palestine, in Iraq…

There’s a lot more going on than just the past 73 years of Israeli occupation – this has been happening for a while. It’s important that people understand the ramifications of the Balfour Declaration and British colonialism in Palestine, to better understand Israeli settler colonialism. It wasn’t a new phenomenon that started when Israel went into the now Occupied Territories in ’67 – or when Israel was created in ’48 – but rather it’s something that started much earlier.

Notes

[1] Anne: ‘Modern Zionism is a nationalist movement that believes the Jewish people constitute a nation and that their national homeland is the state of Israel (or in the early 20th century, the boundaries of the Mandate for Palestine). It should be noted that there are different types of Zionism, which interpret this definition differently.’

[2] A major military offensive launched by Israel in Gaza. According to Amnesty International, at least 1,383 Palestinians, including 333 children, were killed by the Israeli military. Palestinian armed groups killed thirteen Israelis, including three civilians, in rocket attacks on Southern Israel.

You can read Anne’s co-authored article ‘Perceiving Palestine: British Visions of the Holy Land’ here. Anne is also a volunteer archivist for the Palestine Exploration Fund, which is currently engaged in reckoning with its colonial past.