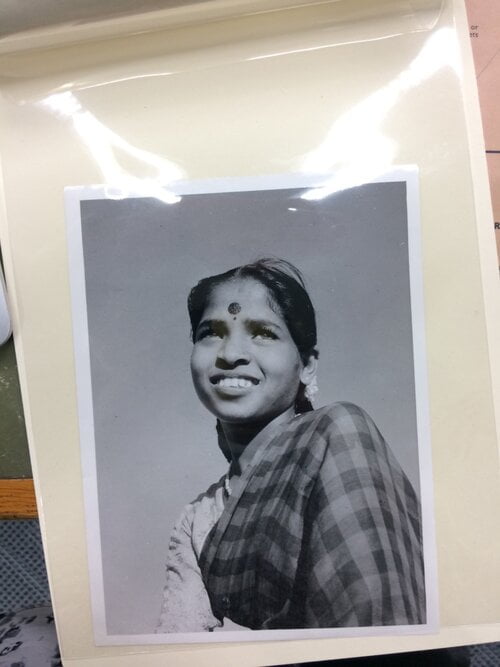

Image credit: Aarzoo Singh

Continuing our August deep dive into the history of forced displacement in the British Empire, MBC interviewed Dr Aarzoo Singh, who recently completed her PhD at the university of Toronto.

Aarzoo’s research looks at how physical objects can tell unwritten, non-verbal histories of Partition, the 1947 division of British India into India and Pakistan, which led to the violent displacement of millions of people.

MBC volunteer Emily Beswick spoke to her about her family’s ongoing experience of Partition, whether colonial archives can ever give space to the stories of colonised people, and how museums and archives can reframe the way they engage with physical objects.

MBC: Could you briefly explain what your research subject is and what archives you are using?

Aarzoo Singh: My research investigates how physical objects can tell unheard, intergenerational histories of displacement for people in the South Asian diaspora. I look specifically at those who experienced, and continue to experience, the Partition of 1947.

The histories told by these objects are different from the official histories of Partition. Written histories, through their very form, have often privileged the coloniser’s voice, whilst silencing the everyday lived experiences and narratives of the violently dislocated victims of colonisation. Much of what was experienced during Partition was not written down but communicated in non-verbal ways, and I look at how meaning is understood in non-verbal ways through physical objects.

My research acknowledges that there are some spaces of violence – colonial, racialised and gendered violence – that are beyond words. I ask how those who continue to experience that ripple effect of intergenerational violence, including families and communities, can make sense of their own experiences, in a way that does not prescribe existing colonial narratives upon them. This is where alternative ways of knowing that are outside mainstream Eurocentric, Western frameworks can emerge.

“Much of what was experienced during Partition was not written down, but communicated in non-verbal ways.”

I know that your work is influenced heavily by affect theory, which is quite an academic concept that can be hard to understand. Could you give an example of how you would ‘read’ a physical object for those histories of displacement?

Aarzoo’s grandmother’s necklace. Image credit: Aarzoo Singh

My grandmother had a wedding necklace which has been passed down to myself and my family. I don’t know much about her story – she died before I was old enough to know her – but she was a typical woman of pre-colonial India. She was under custody of her family before she was married off to her husband’s family at the age of 16, when she came under his custody. Most of her experiences had been decided for her, either by patriarchy or by the nation.

She didn’t have a lot of things but this necklace was one of the few things to her name, as it was part of her dowry. She almost lost it many times. When she was married, it was almost taken from her; she almost lost it again during Partition because everything had to be left behind, but she fought for it. As someone who never really had a space to say what she wanted, this was one thing she actually fought for. She demanded to have it back, she fought with her in-laws to have it returned.

I can’t tell you what her relationship with her marriage was like, but I know that this thing meant something to this woman and it embodied a few choices she made that meant something to her. The necklace carries within it a cumulative history of emotion—this is its affectual currency. In knowing that there is a story, something outside of this prescribed narrative, there is a site for recovery.

Were there any personal experiences that influenced the topic you chose?

I came to this topic because it is about me, my family, and my familial history in many ways. I’m a descendent of these histories of displacement: Partition as an event essentially defined the ways in which I have ended up where I am in the world, because of my great grandparents, my grandparents, my parents’ experiences with it.

“I’m a descendent of these histories of displacement: Partition as an event essentially defined the ways in which I have ended up where I am in the world.”

But even though it’s such a central part of many Indians’ lives to date, it is largely a topic that is silent in Indian public discourse. There were never official hearings, trials, or even memorials, about Partition within India. It’s taken up academically and artistically, but not in an official national way. It’s clearly this collective trauma that’s still being worked out, on both a micro and macro scale.

As a member of the South Asian diaspora whose familial history is wrapped within the colonial narrative of India, I’ve grown up noticing how feelings of belonging can be provoked through the passing of physical objects. The few ways in which my family did talk about Partition would be through stories that came up while looking through old things – for example, my grandmother’s necklace would provoke a story about how it was carried across the border.

I’ve been left in silence many times with the physicality of my familial objects that survived Partition, holding them in my hands, and trying to allow for their presence to be enough to know things I cannot know. Silence does not necessarily mean nothing is being said. The ways in which official records of Partition have been accepted as the main narrative of what happened often erases these other sites of knowledge.

In your research you also used ‘official’ archives. What do you mean by that, and what were your experiences of using them?

Photograph behind protective material in UK archive

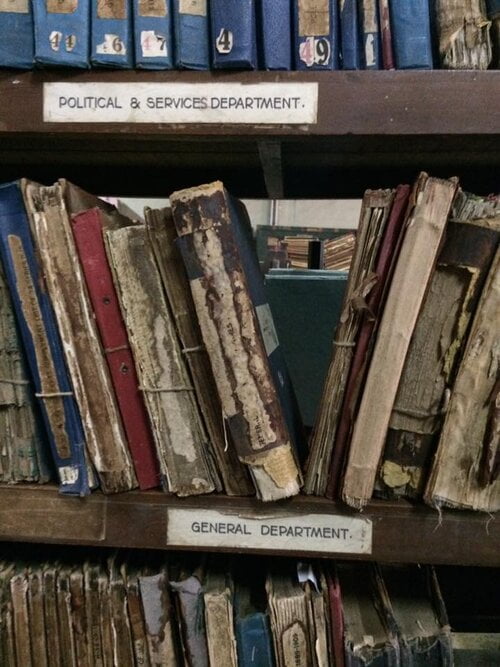

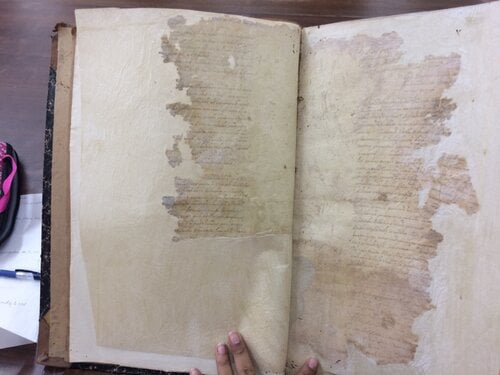

Books in the Mumbai archives (Copy)

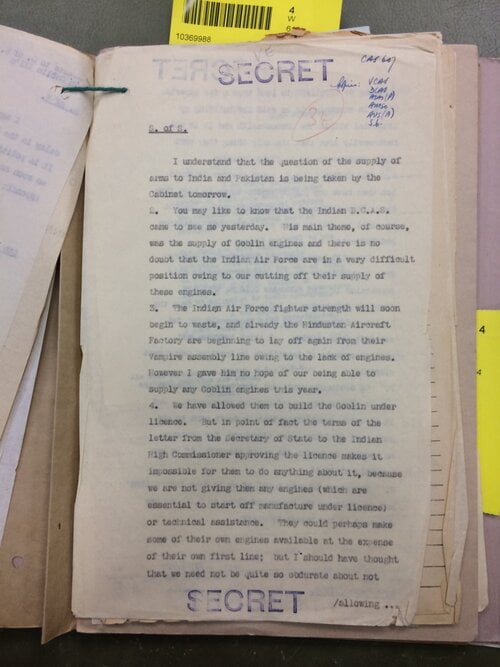

A document held in the UK archives (Copy)

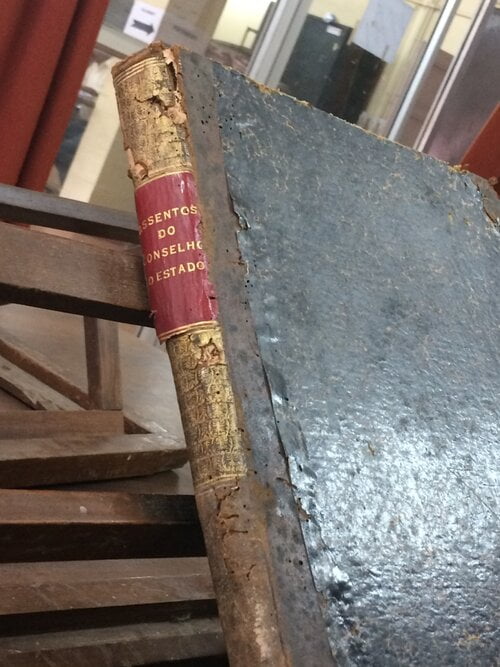

Battered spine in the Goa archives (Copy)

I looked at the archives in which countries will go to for their official collective memory about their past. These are everything from official, national archives to museum spaces to exhibition spaces – any space where public memory chooses to collectively create their identities about their past and present. I looked at archives in India and also the UK, Portugal and Spain, because those were the three main places of ex-empire that affected the history of India.

Actually, my most revealing discovery was not the content of the archival spaces, but more the ways in which archival objects were handled. In the UK, Spain and Portugal, national archives are organised with great care. There’s an element of preciousness that accompanies this process: temperature-controlled rooms, possessions being carried in and out in clear plastic bags, security checking, white gloves, paperweights, all this kind of stuff to handle time-worn documents.

The messaging is clear: these artefacts are of the past. The intermingling of present conditions is not to interfere with their authenticity. I came away from these experiences understanding that these processes reflected the cleansing and sanitising these histories not just in substance but in its deployment as well.

Comparatively, in India, visiting the archives proved to a vastly different experience. In these spaces, antique books and documents are freely handled in humid rooms and spaces. Hand-written pen and ink colonial records are handed to researchers without weights and supports. Neither white gloves nor protective gear is required to use to touch any of these things. The history is very real, very tangible to anyone who chooses to interact with it. In the Indian archives, you find fingerprints and tears in the pages. You can see human traces on the objects.

Any local Indian who needs to consult building records or city plans for undertaking contemporary ventures would still have to access these documents that are hand written by British colonial officers. In a sense, I found that the past is not really in the past for former colonies. The colonial hand is still very much present in the everyday, and this is most evident in the treatment of histories within those archival spaces.

The past is not really in the past for former colonies. The colonial hand is still very much present in the everyday.

Touching a document in the Goa archives. Image credit: Aarzoo Singh

Of course, colonial archives exclude and speak for the lives of colonised people. Do you think there is a way of telling their stories through such archives?

The framework of the archive itself is inherently Western and colonial. So often the voice that is presented in the archive is that of the coloniser, in the coloniser’s language, framework and site of understanding.

For example, some non-Westerners do not differentiate between fiction and history. But in Western archival space these histories of non-Western spaces are forced into frameworks that don’t necessarily make sense of those particular contexts. Oral narratives or indigenous ways of knowing are often discarded within Western tellings of history. As Michel Trouillot [Canadian historian] says, ‘any historical narrative is a particular bundle of silences’. [1]

The scholar Diana Taylor says to think deeply about this issue ‘would require scholars learn the language of the people from which they seek to interact and treat them as colleagues rather than informants or objects of analysis’. [2] This would force us to rethink what counts as a valid source. Taylor suggests that we take alternative sites of knowledge production – such as in my case, familial oral histories and heirlooms – as serious systems of learning and transmitting knowledge. These other sites allow us to expand what we understand as ‘knowledge’.

Has your work stimulated any thoughts about how museums or archives could reframe the way they engage with their objects?

Françoise Vergès discusses the possibility of an alternative museum experience which attempts to address the ongoing colonial logics of object-based museums. She calls the project ‘a museum without objects’, which is ‘neither a virtual museum nor a museum of images and sounds’. This museum ‘would not be founded on a collection of objects’. Rather, ‘the objects would be one element amongst others’ and the museum would confront ‘the absence of material objects through which to visualise the lives of the oppressed, the migrants, [and] the marginal’. [3]

“What does an ever-evolving museum or archival space look like?”

Often in this line of discussion we talk about colonised people as being silenced within these museum or archival spaces, and I think it’s really important to note they are silenced, not silent. Just because their narratives aren’t always being told doesn’t mean they do not exist. Some of the work that seeks to look at non-verbal ways of communicating the past allows space for those narratives to present themselves. Vergès’ idea of the museum without objects is a really interesting alternative new way of thinking about archival spaces.

I don’t think there is one answer to this question, because the answer cannot be static. It has to evolve with the conversation, and I think this is the fundamental problem of colonial archives – they take up the framework of being fixed. But these narratives are as fluid as the people they are talking about. So what does an ever-evolving museum or archival space look like? It’s a big question.

That brings us to the question of whether you can fundamentally change any institution which is rooted in colonialism.

It’s tough. I think critique is important, because obviously recognising the issue is step one in addressing the issue. But it makes me think of that famous Audré Lorde quote where she says ‘the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house’. People get really scared about what actually needs to be done – the whole thing needs to be completely dismantled, destroyed, rebuilt from the ground up.

Notes:

[1] Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and Production of History.

[2] Diana Taylor, The Archive and the Repertoire: Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas.

[3] Françoise Vergès, ‘A Museum Without Objects’. https://criticaltheoryconsortium.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Museum_Without_Objects_by_Franc%CC%A7oise_Verge%CC%80s-1.pdf

You can read Aarzoo’s published paper ‘Recovery after the Rupture: Linking Colonial Histories of Displacement with Affective Objects and Memories’ here.