For the latest instalment of our Paper Trails series, MBC volunteers Suhayl and Beth discussed their research projects together.

Beth: How would you describe your research and your main research interests?

Suhayl: I am a researcher and scholar based in Nairobi. My main interest within the academy is a critical analysis of colonial memorialisation and how we archive our histories. My research is about the misrepresentation of subaltern histories and it’s about remembering our histories and building what we want to see, especially from a critical anti-colonial lens.

I’m interested in the – manufactured – barriers that are put in place to separate us from our histories. While there is a growing focus on reparations and the repatriation of our artefacts and our stolen histories, it remains very difficult in terms of cultural access and academic access. We’re blocked with the bureaucracy and we’re told you can’t have access to this because we know your communities won’t be able to take care of it. I’m also engaging with this question in terms of when our histories are returned and our artefacts are repatriated, who is going to get the artefacts? Is it the communities or is it the colonially manufactured nation state?

B: And that’s why I think we have so many crossovers with everyone at MBC in terms of these questions about memorialisation and the barriers around that. How does academic research inform social justice activism? Can it?

S: I’m primarily going to say it cannot. All through my academic life, especially when I was doing my undergraduate, what I was learning was manufactured histories that were brought about to pacify our histories and to submit it to white gaze. It was primarily taught, colonialism happened, here are the positives and the negatives of colonialism. But there’s no positives of colonialism. Later on in my undergrad I thought this can’t be real! I started actively engaging with Mau Mau veterans, and I came across Field Marshall Muthoni. That really shaped my practices going forward.

One thing I should make clear is I stopped actively engaging with decolonization because I think it has become a token, especially in the academy. I’m actively engaging and seeing myself as an anti-colonialist, actively confronting and implicating the violence of colonialism in institutional structures and in our basic day to day activities. One thing that really frustrated me was the stealing of information and knowledge. When I started sitting with Field Marshall Muthoni, she kept on bringing up stories of, you know, there’s this British journalist who came and said they were making a film about me, but I haven’t heard from them. Years later, we’ll see this documentary without any acknowledgement. What’s happening here? Someone who fought in the struggle, their information is being stolen and it’s being packaged to suit a particular privileged ‘intellectual class’. I realised that I don’t want to be part of this. This is literally one of the last things I want to be a part of. However, if we all just withdraw from this, rather than directly confronting and implicating this issue, we’ll let colonialism continue infiltrating and indoctrinating students to come in the future. So how are we supposed to fight, within in confines of the academy?

B: You really hit the nail on the head in relation to knowledge production. Am I the knowledge producer because I wrote an article and it got into a journal, or are the women that share their stories with me the knowledge producers? That needs to be the citation. I heard a fantastic paper at a conference last week by Wunpini F. Mohammed, talking about the fact that we should also be citing knowledge production systems from certain ethnic groups. So, I really commend your approach.

S: Exactly. It often becomes the author of the academic article who ‘discovers’ something. And it reimagines people and places as sites of study, rather than sites of indigenous knowledge production.

B: It’s another form of extraction and that’s what colonialism was based on in so many ways. So can academic research ever be decolonial?

S: Primarily, my answer is no. For the academy to be truly decolonized, it must be abolished, and we must build it up again. But the people who want to decolonize the academy have no practical access to these spaces. I am now seeing younger people engage with histories and anti-colonial thinkers that I only got to know until later in my academic life. We only got to access these histories because we had the privilege of being in proximity of academy. But this information is still heavily guarded. To be decolonized, it needs to be truly accessible. For that to happen, we need to stop seeing the academy as a site of commercialization and profit and see it as a space for knowledge sharing and producing new knowledge. This cannot happen in a silo. So for me, the academy needs to be abolished and we need to restructure and look at it differently.

B: I want to ask you about your role with the Museum of British Colonialism. How does MBC relate to your research interests?

Field Marshal Muthoni wa Kirima, video by Suhayl Omar.

S: Again, it’s the violence of the academy that brought me to MBC. I had been looking for internships and I thought, I am not going to be exploited! That in itself is a privilege, to be able to resist exploitation. I was already archiving a lot of visuals and recordings of Field Marshall Muthoni and other Mau Mau veterans so it was a perfect fit. I came to realise that the information that I was collecting should not be for commercial purposes, it’s for people to understand the histories. MBC has grown into a very beautiful network of transnational scholars and activists. It has brought me to a place where I understand that the work I’m doing – we’re doing – is about sharing rather than producing.

B: One of your key research themes is memory. What is it like researching that in Kenya? What are some of the implications that come with constructing and sharing some of these memories?

S: During my research it dawned on me that we need to humanise research and our research subjects. I realised that academic ethics were not enough. There’s also moral ethics that we overlook when engaging with people. Memory revolves around a lot of things and the memory I’m looking at is violent memory. It’s memory that people might be seeking to hide or not speak about. Because once you speak about violent memories, it evokes emotion. How is a researcher supposed to handle emotion? Are we just supposed to sit there with a straight face? I’ve built a sense of community with people, not just looking at them as a site of study. It then becomes very easy to understand that we’re dealing with humans. We have to talk about emotion, we have to engage with people as human beings.

B: Exactly. You’re dealing with people’s trauma and intergenerational trauma. That’s where your research practices give me so much to learn from and other people who are operating within the academy, because our ethics processes, they’re there, but are they as effective as they can be? As you say, it’s about community building. And that also can produce healing processes and supportive structures. An extractive approach is never going to be able to do that. What are you currently working on in terms of your community organising?

S: We’ve been looking at different perspectives to memorialisation. For example, planting trees in memory. A tree is going to give back to the community, creating gardens where people can rest. We can think of this as an act of protest, because it’s so hard having a public space. We’re trying to engage with new mechanisms of remembering. We know that in the future, we won’t have access to Mau Mau veterans and we want to know that their legacy won’t be pacified into simply ‘this is someone who fought colonialism’. And that’s it. While we’re remembering this history, we are fighting for progress and liberation within our communities.

B: You’re bringing so many facets of what it is to have been in a place that was so heavily colonised by a European power like Britain. Thank you so much.

S: So how would you describe your work Beth?

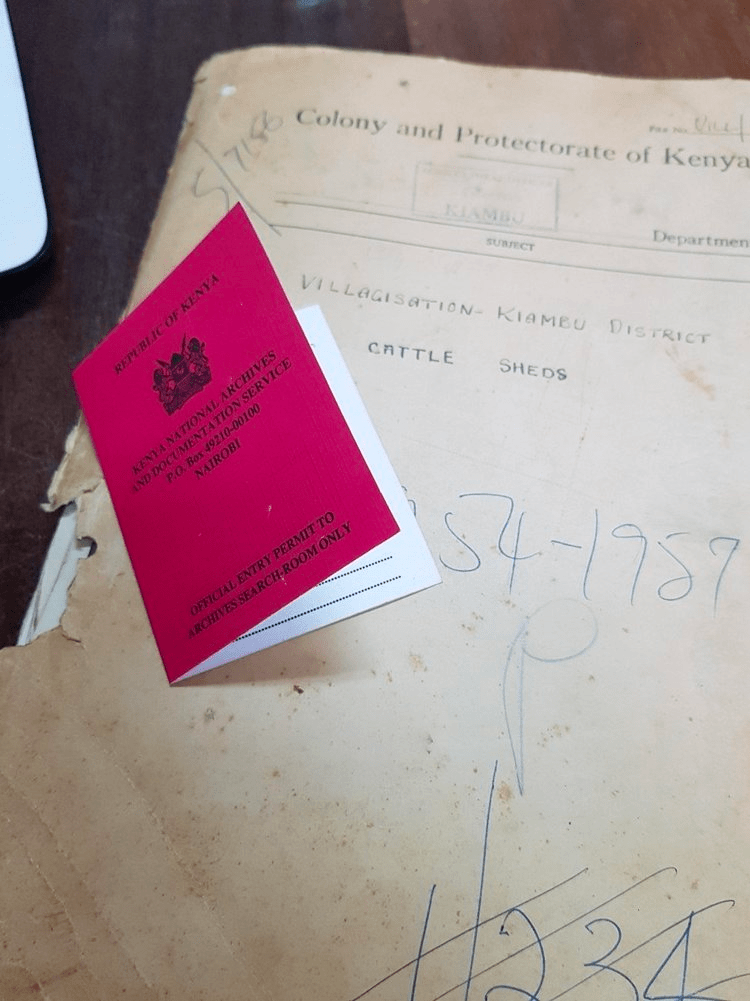

B: I’m a lecturer at the University of Bristol, lecturing in the history of modern Africa. Before that, I was doing my PhD at the University of Reading, which was largely looking at the counterinsurgency campaign fought by the British in Kenya during the 1950s, the so-called ‘Emergency’ period. My specialism within that is thinking about how women and girls experienced this conflict, particularly Gĩkũyũ women and girls. By doing so I looked at forced resettlement, what is known within the colonial records as villagisation’. I looked at how women and girls lived their lives within the camps that were created by the British. This includes how they encountered colonial officials and the wider colonial administration. I also looked at humanitarian involvement, the British Red Cross Society, and how they worked with the colonial administration to implement a wider social engineering project as part of their counterinsurgency campaigns. So I’m a social historian, particularly interested in Gender and Women’s History.

I’m interested in oral history and oral traditions. A lot of my work has been using oral history interviews to kind of counteract what we find in the colonial records. Because the colonial records tell a very particular story of what the British were doing in Kenya during the 1950s. So I’m kind of engaging in oral history interviews with Gĩkũyũ women to kind of rebalance that and bring in those marginalised voices and testimonies. That’s kind of how I then became involved in the Museum of British Colonialism. I was in Nairobi in 2018, when MBC was starting and it became clear that I was basically conducting research that aligned with its overall mission to communicate these histories of the Kenyan emergency. So I started writing blog posts, doing some fieldwork research for them, conducting some oral history interviews, and it’s kind of gone from there.

S: How women and girls are affected by colonialism is something people rarely look at. What pushed you to look at Kenya and especially these women and girls?

B: Very much for those reasons. Women’s voices are continually marginalised. I became interested in the Mau Mau as an undergraduate, which was when a high court case was happening in London, when Mau Mau veterans successfully sued the UK Government for the atrocities that they committed in Kenya in the 1950s. And so this is happening while I’m picking my dissertation topic and I just thought it was really fascinating. I knew nothing about it, I was brought up in a British education system, you learn about World War Two over and over again. For me, it was kind of this process of re-education, I was totally ignorant. I went to a couple of the court hearings and the public gallery and that kind of got my interest in the topic. I didn’t have the funding to do any fieldwork at this stage, so I had to look at this particular conflict from a British perspective. I started by looking at the colonial records that were in London, and did an institutional history of this, thinking about military processes and that side of things. I always knew that looking at these colonial records, there was literally nothing on women. There would be records on women’s detention camps but that was as far as it went, there was no understanding of how women lived their lives within this period. And it’s an enduring challenge that any historian of Africa overcomes, because African women are completely written out of archival records. So from there, I knew that my PhD was going to be looking at how women and girls experienced this.

S: You’ve mentioned the British perspective. Obviously, you have access to this knowledge, but people living in Kenya and who have been affected by this violence do not. How has your Britishness shaped your research?

B: At school I was learning about African history through this idea that, wow! Britain had this industrial revolution and then they went to all these different places in the world and they gave all these opportunities and found all these amazing resources. And you’re a child and you hear a whitewashed history. But that was my education. You point out clearly that I have had the ability to learn and research this history from my position in British institutions with access to the colonial records because they are kept in London. They should be in Kenya. I then have access to the research funding to be able to go and do fieldwork in Kenya. I do think about this every day, about whether I should even be taking up space in the academy doing this. But then, on the flip side, knowing that I have that privileged position, with all that access, it’s then what I do with that and how I work through that. So for me, the core part of my work is, if you’re going to be anti- racist and anti-colonial, it’s a day to day process. You don’t just tick the box. It’s that day to day process that we undertake to break down internal barriers, biases, etc.

This is also why I’ve put so much of my energy into the Museum of British Colonialism. Because as much as we’re doing good to decolonise institutions and history curriculums, I don’t think it goes far enough and it becomes quite tokenistic and performative. Whereas being able to work with an organisation like MBC, it feels more meaningful in so many ways, because it’s about us communicating these histories in an accessible way. We’re still not there yet, we still have our own barriers to overcome, like producing more of our work in different languages. It’s an ongoing process that we’re having to work through. So for me, it’s about using my privilege as best I possibly can and being as best an ally as I possibly can. And making sure my work is reflecting that. I don’t think we always get it right, though, I think we have to talk about our positionality. For me, particularly as a white woman, talking about black feminism and learning about black feminism, and interviewing Kenyan women about their experiences in villages, I can deal with my positionality as much as I want but it is always going to impact the way I’m engaging with my research. This is also compounded by the fact that I’m an Early Career Researcher. So I’m also in a really precarious place within the academy to be able to do those things.

S: I think that’s important. You’ve worked on forced displacement during colonial times and with the current British government, we are seeing a manifestation of this again in relation to Rwanda. What connections can you make from your research with what’s happening now? Is it unprecedented or something that we should have seen coming?

B: What I would say is forced resettlement has a very long history and it will continue to have a history. I come at forced resettlement, largely from a military point of view, that’s been the focus of the way I’ve researched it. When ‘villagisation’ was introduced in Kenya, and Britain may have called these spaces villages, but I make the argument in my thesis that ‘village’ as a term is being used to occlude the violent practice that it is. This is also being introduced in Kenya in the 1950s. It’s just after the Holocaust in Europe, where Germany introduced concentration camps, which turned into extermination camps. So this whole idea of encampment has a very long history. We can pull it back to the British in South Africa, the Spanish in Cuba. Britain does a rebranding of this process, and they call it a village, and it’s to house women. So we’ll, we’ll send out some pictures of kids playing on slides. And we’ll show a well stocked shop where a woman is very happily serving someone. That’s their public facing imagery. And then when you speak to women that actually lived in these so-called villages, they depict these as concentration camps in all but name. That these are spaces where they are forced into, they are tortured, they are mistreated, there are heightened levels of malnourishment and starvation. We see this happening throughout history and it will continue. Similar strategies have been used post 1950s. It’s a key aspect that military and governments choose to use in terms of thinking about guerrilla warfare and insurgencies. Displacement and relocating people into sort of concentrated zones is the easiest way of dealing with this. And it also then brings in opportunities for social engineering, because now you have a large population concentrated, you can begin a social engineering process. I think it’d be very harsh to say, we should have seen this coming because we have to know a lot about history to know when things are going to be arising. But there is a pattern there. And from a military perspective, it’s a really effective tool to use, so that’s why it’s used.

S: It comes back to who gets to access these histories and how these histories have been intentionally hidden.

B: I always call it Britain’s dirty little secret. With my students, we talk about what is the purpose of an archive? How can archives be violent? What narratives are governments constructing? The point of archive creation is constructing narratives about your national history in many ways. That is something that the British government have been prolific in, in building an archive to tell a certain story. And that’s where I, social historians and predominantly activists are challenging that and looking at different means. The official records are really important and they reveal a lot, but there is also a negotiation of power over this narrative. We’ve focused on them so much and we’ve forgotten that there are so many other ways to seek out this history. Women’s voices are being neglected in all of this because we can’t find women’s voices in these records. This is a timely bit of research as well because we are losing that generation of people that experienced the conflict. So for me, oral history has never been more important in actually challenging that ongoing power negotiation.

S: How can your students confront colonialism?

B: My main lesson to all my students always is to critically engage with whatever they read. And that doesn’t mean find the thing that’s wrong. It is critically engaging, it is asking why. That is where you start to see how sources have been constructed, why they’ve been constructed in certain ways, and how that has created an environment in which historians have actively supported Empire. They played key roles in empire building to create these narratives. I think collaboration is incredibly important. That’s what Museum of British Colonialism is all about, collaborating and sharing resources, redistributing sources as best as you possibly can. Finally, we shouldn’t be making space for African voices and scholars, scholars and students in the so-called Global North shouldn’t be holding the authority to invite people into the space. We should be recentering who the authoritative voices are in the narrative: scholars and individuals in the so-called Global South.

Suhayl Omar is a Kenyan based researcher. His interests with MBC lie in theorising how epistemologies of violence and colonialism have affected the re-membering, museumification and misrepresentation of our resistance(s) when it comes to preserving subaltern histories.

Beth Rebisz is a Lecturer in the History of Modern Africa at the University of Bristol. Her research interests include gender and women’s history, African oral histories, histories of humanitarianism, welfarism and development, counter-insurgency warfare, colonial violence, subaltern methodologies, and digital humanities.