Britain’s monarchy has a very close relationship with Empire that dates back to before there was even was a Britain. Before the union of Crowns in 1603 or the Union of 1707, both the Monarchs of England and Scotland sponsored colonisation efforts across the globe.

Ireland

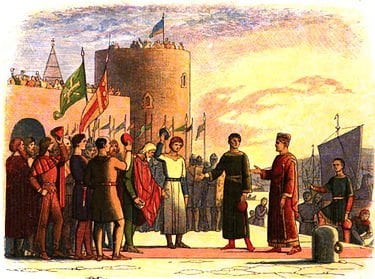

19th Century artistic depiction of Henry II landing in Waterford as part of his conquest of Ireland

It was England’s monarchy that first began expanding its power overseas. The first English overseas colonies were established amidst the Tudor conquest of Ireland in the 16th Century. English monarchs had laid claim to being Lords of Ireland since 1175, after Henry II landed an army in 1171 and demanded loyalty from the Irish clans. But their control over the island was tenuous at best and English monarchs only ever really directly controlled the Pale – a stretch of land based around Dublin. Though there had been some Anglo-Norman settlement, intermarriage and the strength of the native Irish chiefs diluted any power that an English monarch might have hoped to wield.

The Tudor Conquest lasted over 70 years from c.1540 to 1603, and the Lordship of Ireland was abolished in 1542 and replaced by a new structure, the Kingdom of Ireland. This was a puppet regime of the English monarchy.

The first English colonies in Ireland were established in the 1550s under Mary I. These took the form of ‘plantation colonies’, whereby the Crown settled Protestant English colonists on Irish lands in attempt to anglicise and ‘civilise’ Ireland. Alongside this, native Irish lordships were disarmed and English rule was established over the whole island. Ireland was now governed according to English law and a puppet English Parliament in Dublin.

These plantations served as the testing ground of Empire. Many of the fiercest advocates of the colonisation of Ireland, specifically the Western Province of Munster, became deeply involved in later English colonisation efforts in the Americas. This group of ‘West Country Men’ included Walter Raleigh, Francis Drake and Humphrey Gilbert. The colonial violence inflicted on Ireland would later be replicated across the globe. Ireland was the laboratory for the English Monarchy’s imperial ambition.

Scotland’s monarchy also made ventures into colonisation. James VI, anxious to secure his realm, approved a colonial enterprise aimed at the Isle of Lewis in Na h-Eileanan Siar, an island chain off the coast of western Scotland. This enterprise under what was known as ‘the Gentlemen Adventurers of Fife’ was unsuccessful in supplanting the native islanders and eliminating what James saw as the ‘Irish’ influence. However, this does hint at the anti-Irish sentiments that motivated Scotland’s monarchy and its early attempts at colonisation.

Colonial trade and transatlantic slavery

The Tudors sought to colonise North America and expand England’s control of trade routes. In 1584, Elizabeth I granted Sir Walter Raleigh a charter to colonise Virginia. Elizabeth also granted a charter to the infamous East India Company in 1600 and with it, a monopoly of all English trade east of the Cape of Good Hope and west of the straits of Magellan. The company would establish forts and gain control over vast swathes of India. The EIC would eventually be replaced by direct British rule, but this form of ‘corporate colonisation’ appealed to the Crown.

The coat of arms granted to Hawkins

Elizabeth’s rule marks the first recorded involvement of the English monarchy in transatlantic slavery. In 1564, Elizabeth granted a large royal ship, the Jesus of Lubeck, to the slave trader John Hawkins in exchange for a share in the profits from the voyage. The English Crown supplied Hawkins with provisions and guns for his voyage. Hawkins set sail with the Jesus and three other ships under a royal banner, journeying first to West Africa and then on to the Caribbean. Hawkins returned in 1565, having captured and sold over 400 Africans on his voyage. Elizabeth I rewarded his efforts, granting him a coat of arms, upon which was a black African bound in ropes.

The monarchy is at the heart of this early history of English and Scottish colonialism. The impulse to expand overseas came from a desire to ‘civilise’ Irish and Gaelic elements within their own geographic orbit. Whilst Scotland’s attempts failed, the persistent attempt of England’s monarchy to pacify and ‘civilise’ Ireland gave birth to the methods that Britain would unleash on the world. Whilst the methods of colonialism were first developed in Ireland, the monarchy found the capital that would fund imperial expansion in the slave trade. It is important to recognise this history, as it shows that the monarchy was involved with the project of Empire as active contributors, not passive bystanders.

Further Reading

The Queen’s Slave Trader: John Hawkyns, Elizabeth I, and the Trafficking in Human Souls by Nick Hazelwood