Edward VII (1901-1910) focused more on Britain’s relationship with European rivals than the Empire. His short reign was the prelude to the First World War, and the accompanying social divisions in the UK kept him too busy to meaningfully impact on the Empire. His earlier tours of India as Prince of Wales were of far more relevance, as they were the origins of the royal Commonwealth tours. Edward played an active role. This symbolic and ceremonial embrace of the Empire was further cemented by an evolution of his title in include the white dominions, whereby in 1901 he was crowned ‘King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and of the British Dominions Beyond the Seas, Defender of the Faith, Emperor of India.”

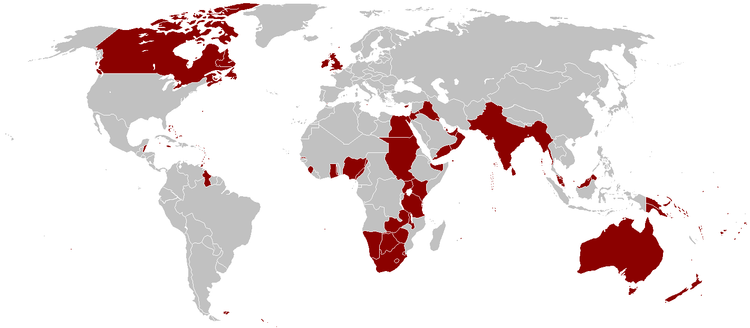

The British Empire at its greatest territorial extent in 1921.

The Empire on which the Sun Never Sets

The reign of George V (1910-1936) was when the Empire reached its territorial zenith in 1920. Like his father and grandmother before him, George V was a symbol more than anything. Like his father before him, he had participated in imperial tours, opening the first session of the Australian Parliament in 1901 on behalf of his father.

As King, George continued this practise of utilising junior members of the Royal family for shoring up imperial rule. Indeed, it was under his reign that the first Royal Governors-General were appointed as Viceregal representatives in the white dominions. Between 1911 and 1945, Canada, South Africa, and Australia all got at least one senior royal Governor-General. These postings accompanied the transformation of the Empire to the Commonwealth. George V personally hosted the Prime Ministers of the White Dominions in the 1926 Imperial Conference whereby for the first time, the UK recognised the white settler dominions as equal in status to itself. Again, whilst George V played little role in achieving this outcome, he nevertheless was the symbol for white imperial unity and co-operation.

The Nizam of Hyderabad swears alliegance to George V as the Emperor of India

George V also personally partook in the pomp and circumstance of imperial rule directly. In 1911, he became the first King-Emperor to be personally present for his ‘Delhi Durbar’ in India. During this elaborate ceremony, hundreds of Indian Princes came forth to pledge their allegiance to George V as the recognised heir of the Mughals. George V also ensured his family served in this capacity as well, most notably when his second son, Albert, Duke of York and future George VI, opened the 1923 British Empire exhibition on behalf of his father.

Rulers of Racism

George V’s successor, Edward VIII, was not on the throne long enough to meaningfully affect imperial policy. His swift abdication in 1936 saw to that. However, as Duke of Windsor, Edward did play a meaningful role in governing the Empire. In 1940, he was appointed Governor of the Bahamas. Such a far-away and relatively minor posting compared to the more sought-after ones such as India or Canada seems odd for a former King. It was his alleged Nazi sympathies that played a role in his appointment, ensuring he was far away from the war in Europe. Despite that, he dutifully carried out his role in the name of his brother, George VI. Edward was on record as disdaining both his posting and the non-white population under his charge. He once said of Étienne Jérôme Dupuch, a Bahamian MP and newspaper editor that

“It must be remembered that Dupuch is more than half Negro, and due to the peculiar mentality of this Race, they seem unable to rise to prominence without losing their equilibrium”

Such unabashed racism was common for Edward VIII, who as Prince of Wales in the 1920s wrote to his Mistress during a tour of Barbados, saying of the island

“It’s a unique sort of scenery very ugly & I don’t take much to the coloured population who are revolting.”

Lord Mountbatten (centre) sits as Viceroy with Jawaharlal Nehru, Lord Ismay and Mohammad Ali Jinnah (left to right)

‘Cut and run’ Coloniser

Whilst his brother’s brief reign was dominated by his abdication, George VI’s reign was dominated by the Second World War. Nevertheless, several notable imperial developments occurred involving the Monarchy. Whilst George VI served as the last Emperor of India, his cousin Lord Louis Mountbatten, Earl of Burma and Admiral of the Royal Navy, served as the last Viceroy of India. Mountbatten was the last Royal to have a direct and unfettered say on colonial policy, serving as Viceroy of India for 2 years after he was appointed by the new Labour Government in 1945. It was under his term as Viceroy and indeed, partly due to his influence, that India was partitioned along religious lines. Whilst many say the partition and the subsequent violence was inevitable due to Hindu-Muslim tensions, there is substantial evidence that Mountbatten rushed the process of British withdrawal to enable the British to ‘cut and run’. Mountbatten’s shifting of the date of Indian independence from 1948 to 1947 created uncertainty and millions of people migrated in fear of being on the wrong side of the borders, which had not been announced yet. The death rate is debated but it is estimated that anywhere between 200,000 to 2 million people died in the ensuing chaos. Mountbatten stayed on for a year after Indian independence as the Governor-General, before returning to the UK and resuming his military career.

Resisting Irrelevance

George VI meanwhile continued to preside over decline. Like his father, George VI presided over the transformation of the Empire into the Commonwealth. His other family members certainly joined him in this. The future Queen Elizabeth II made a famous radio declaration in 1948 whilst on tour of South Africa, saying she would ‘dedicate herself to this great imperial family to which we all belong’. Such tours were a necessity. In the last 8 years of George VI’s rule, his Empire shrunk massively with the British retreat from India and the surrounding region. UK governments were determined to maintain Britain’s place in the world as an imperial power, believing they could play a role equal to that of the United States and Soviet Union. The Royal Family was an essential part of keeping up appearances and maintaining the great imperial façade. Indeed, the Monarchy sought relevance in the midst of imperial decline by actively encouraging the development of the Commonwealth. In 1949, when it was agreed that Republics were now allowed to be Commonwealth members so long as they accepted the King as the symbol of ‘free association’, George VI accepted and embraced his role.

Ultimately the Monarchy in the first half of the 20th Century became the ‘imperial mascot’. With its political power substantially eroded, acting as the ceremonial linchpin of the Empire and Commonwealth gave them renewed purpose. However, they were not passive. Rather, they were enthusiastic and active in their role as Monarch-Emperors. Just as the Stuarts and Hanoverians had delighted in the spoils of the slave trade, so to did the Windsor Monarchs enjoy their time as Emperors.