MBC’s Andrea Potts spoke with researcher Jade Lindo about British colonialism, beauty standards, and colourism. Jade Lindo is a Design Historian. She recently completed a Master’s Degree in History of Design at the Royal College of Arts/Victoria and Albert Museum and holds a BA in Fashion from University for Creative Arts, Epsom. She is interested in social and cultural histories surrounding identity, hair, and beauty for the Caribbean diaspora and how these relate to histories and legacies of colonialism.

Andrea: What do you research?

Jade: I am a design historian and I look at Eurocentric beauty standards through the history of pageantry. I focus on pageantry in Jamaica in the mid-twentieth century and I trace how a new version of pageantry emerges in the UK with the Carnival Queens. Connected to this is a history of colourism and racism. With that in mind, I also look at bleaching creams: how they have been used and publicised.

A: So first, could you introduce us to pageantry in 1950s Jamaica?

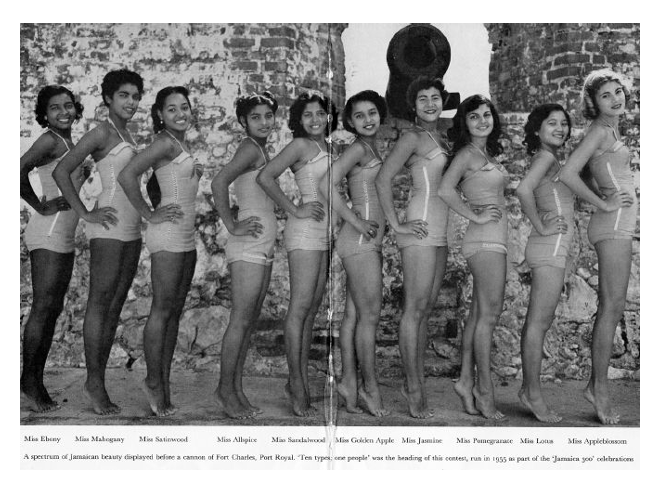

J: Pageantry in Jamaica at this time is interesting. In 1955, there were a series of events to mark 300 years since Jamaica was colonised. This included pageantry. There was a pageant known as the ‘Ten Types, One People’ contest. There were ten women taking part and they were each celebrated for representing different skin tones. It was a way to showcase the diversity and tolerance of Jamaica. So in the mid-twentieth century, this was an attempt to celebrate Jamaica, despite colonisation. But what I found interesting was that within these ‘Ten Types’ of beauty, there were only two categories for dark-skinned women. Most of the categories were for white women and light-skinned women of mixed heritage. One of the categories was actually referred to as the ‘coal’ or Cool Black Woman category and the other was called ‘The Mahogany Woman’. This shows how colonialism shaped beauty standards. Black women were not the ideal and were not seen as feminine or beautiful.

“This shows how colonialism shaped beauty standards. Black women were not the ideal and were not seen as feminine or beautiful. ”

In 1960, separate competitions developed, and each competition would have ten types of beauty. So ‘The Mahogany Woman’ would have her own competition. Even though the language around these competitions was about black women being beautiful, women were still divided up according to skin tone. And these pageants were widely publicised at the time through newspapers. One of the first winners was a woman called Doreen. She was amplified and lifted up as being a beautiful dark-skinned woman. She was celebrated as an example of what a dark-skinned person can achieve. It’s interesting that women with lighter skin were not discussed in this way. They were simply celebrated as beautiful individuals, rather than as representing a broader group of people. Doreen was seen as a marvel because she was a poor black woman, with dark skin, and she was beautiful. That combination wasn’t expected. I found this really interesting and started to think about all of the work that women like Doreen had to do in these spaces. For the dark-skinned woman, it was all about becoming something. So, in the Jamaican context, colourism was really significant. When people came over to Britain, they faced different challenges. Rather than colourism, they faced racism. It didn’t matter how light-skinned you were, you were still black.

The ‘Ten types’ pageant in Jamaica, 1955

A: I find it interesting how beauty standards are so insidious and it’s therefore difficult to undo a lot of learning. You can consciously be aware of a history around a beauty standard and actively oppose it, but nonetheless still want to be the standard because you know that it is accepted by others. And it’s interesting to hear that in 1950s Jamaica beauty standards around the colour of women’s skin were in some ways challenged and in some ways upheld. I wonder if that speaks to that internal struggle.

“This shows the appeal and constraints of a dominant, Eurocentric idealisation of what beauty is.”

J: Yes, exactly. I remember coming across some newspapers clips where women were saying that they were so excited to even be afforded the opportunity to be selected and be in the running to be a beauty queen. It’s hard to resist the satisfaction that comes from someone telling you that you are beautiful and therefore telling you that you are valued and belong. This shows the appeal and constraints of a dominant, Eurocentric idealisation of what beauty is.

A newspaper article celebrating the dark-skinned women who were competing in a beauty pageant.

A: What was your research journey?

J: I initially studied fashion but later did my MA in History of Design. That’s really when I started to focus on social and cultural history and to unpack things more and question the world around us. My research interests within that are actually quite broad. I recently co-curated an exhibition about medicine and slavery at the Royal College of Arts as part of my Masters degree. It looked at how enslaved peoples’ knowledge about the natural world was extracted and used in Britain. I think that together, I’m ultimately interested in identity and heritage. How we inherit who we are. And certainly, when I was working on pageantry for my Masters dissertation, I thought about my parents’ journey. That’s really why I wanted to focus on the mid-twentienth century, around when my parents were born. My parents were born in Jamaica and migrated to Britain. Of course, they were always British, as they were subjects of empire. I felt like I was following their journey but also filling it in with everything else I could find about what it was like to live at that time.

“I’m ultimately interested in identity and heritage. How we inherit who we are. ”

A: And you also look at Carnival Queens in Britain?

J: Yes. Carnival Queens emerged in the 1960s. I was specifically looking at how there was a beauty contest for the Carnival Queens in London. And most woman in that lineup was dark-skinned. So it was very different to colonial Jamaica. But I actually found that some of the people who were really heavily involved in this were also producers of bleaching creams and would publicise and promote them in newspapers and magazines. So again, it’s complicated. On one level, it’s about the commercialisation of beauty, right? What will make you money?

An advert for a bleaching cream.

A: That’s so interesting. It really highlights how thorny and complicated these histories are.

J: Definitely. This isn’t linear. Identity doesn’t work that way.

A: Okay, so what’s next?

J: I am hopefully going to start a PhD next year. And I’m going to look at the relationship between food and identity in relation to women in the Caribbean. So, again, my overall interest is identity through many different cultural and social practices. These practices make us who we are and they are much more complicated that we think.