Colonial Origins

Both Johannesburg Central Police Station and Constitution Hill’s origins lie in settler and extractive colonialism.

THE OLD FORT COMPLEX

MARSHALLTOWN POLICE STATION

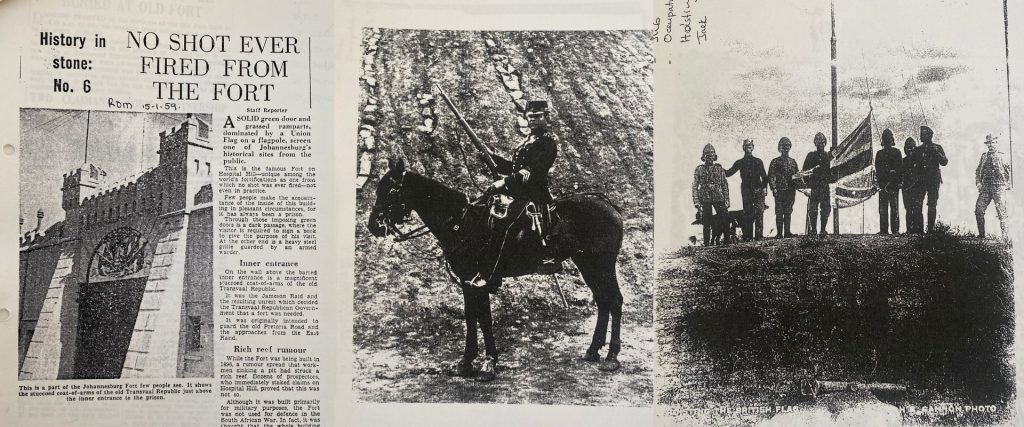

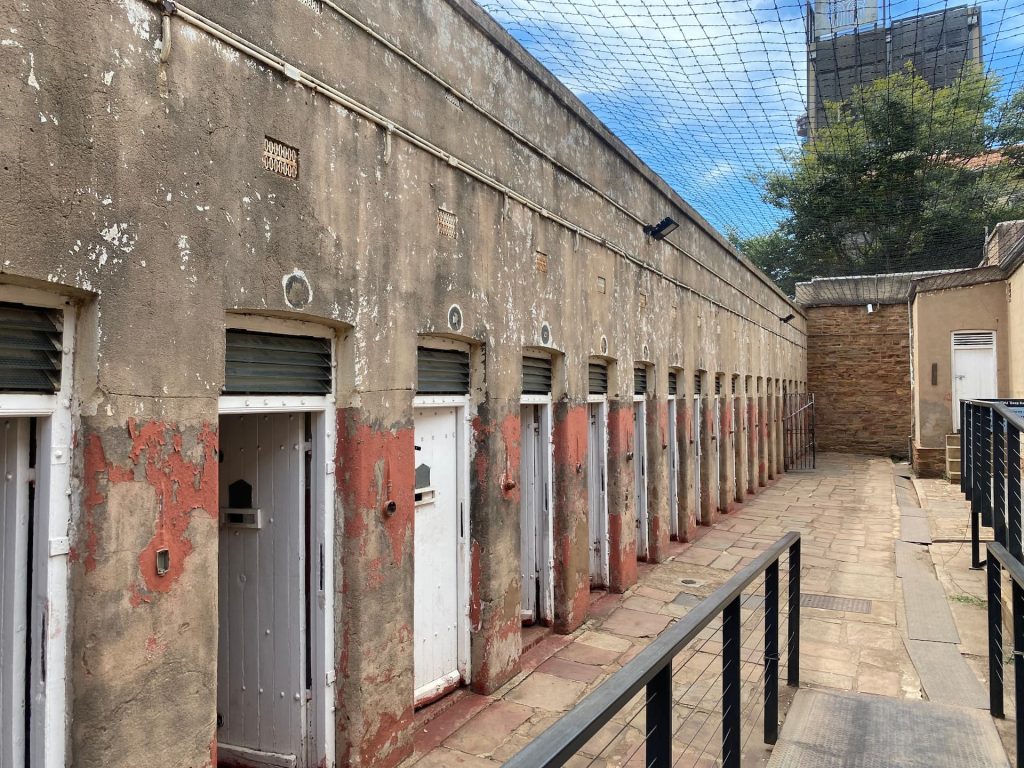

The old fort precinct, unlike other famous apartheid prisons such as Robben Island, was an everyday urban prison. It was built as a fort by the Boers in 1896-1899 to protect the gold mines from the British incursions and to police the newly erected mining town of Johannesburg. It was erected on the northward slope of the Braamfontein Ridge in an elevated strategic military position to ward of any treats. During the South African War (the second Anglo-Boer War), the British Army took control of the fort for a short period and used it to house prisoners of war. The control of the fort by the British, however, did not last long as the Boer’s retook the fort a few years later. Some sources contend that during this time, Winston Churchill was captured and held at the Old Fort before escaping and leading an incursion against the Boers.

During the apartheid era (1948 – 1994) many political prisoners were held at the site alongside criminal inmates, most famously Nelson Mandela, Robert Sobukwe, Oliver Tambo and Albertina Sisulu. The complex was notorious for its harsh conditions including, torture, overcrowding, poor sanitation and disease. Many inmates lost their lives whilst incarcerated at the site.

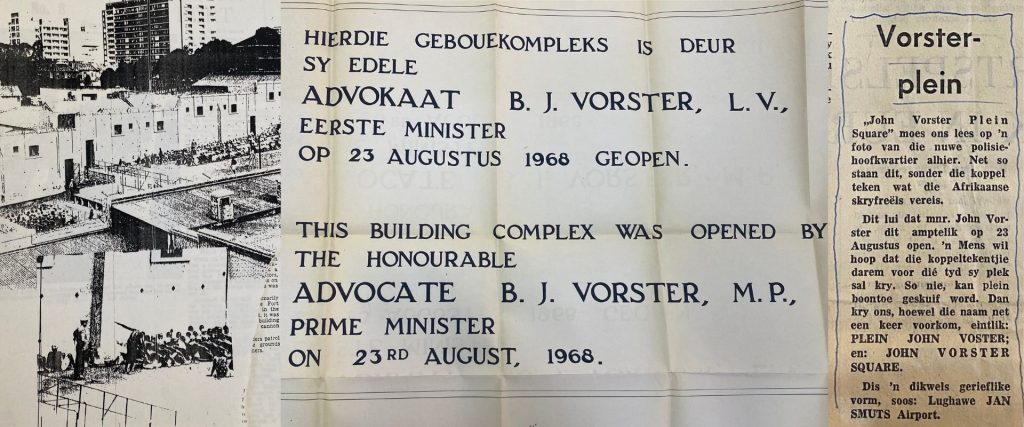

John Vorster Police Station’s roots stem from the Old Marshalltown Police Station built under British Colonial rule which was located on the periphery of the ‘Randjeslaagte’ – a triangular piece of land on which Johannesburg was founded in 1886. After the adoption of apartheid by the National Party in 1948, a need for a new police station arose, and John Vorster Square was built. It was named after John Vorster, a well known hardliner who violently opposed apartheid resistance and created a legal infrastructure to outlaw anti-apartheid activity.

Heralded as the largest in Africa, this ‘state-of-the-art’ modern police station, was opened in 1968 by Prime Minister Balthazar. The building was characterised by its square-shaped, blue structure. It housed all the major divisions of the police force, including the Special Branch dedicated to curbing anti-apartheid activity. It’s reputation as a site for torture and brutality soon followed as the building became a primary location for the detention, interrogation, and imprisonment of anti-apartheid activists. Harsh treatment and excessive violence resulted in the deaths of tens of detainees between 1970 and 1990.

Divergent Treatment

Constitution Hill and Johannesburg Central Police Station are important examples of the inconsistency in the treatment of violent apartheid memory.

FROM PRISON TO HERITAGE SITE

In 1996, with the commencement of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission hearings, momentum grew behind converting The Old Fort Complex into a site of national memory and the home to a new Constitutional Court. The redevelopment of the site in this way became part of the symbolic reparations recommended by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and was used as a site to remember the anti-apartheid struggle by the new democratic state. The vision of the Constitutional Court judges, who are credited for selecting the site, was to juxtapose the brutal history of apartheid using the prisons, with South Africa’s hopes for restorative justice and reconciliation through the new Constitutional Court.

“...the Old Fort precinct in Johannebsurg, an area with a rich but grim history as a prison compound...will be developed as ‘Constitution Hill’, which will become a public space for the city and a symbolic space for the nation, where the Court and human rights institutions will be accommodated alongside museums in the historic prison buildings”

- Competition brief for the design of the new Constitutional Court Building of South Africa - Department of Public Works 1997

FROM POLICE STATION TO POLICE STATION

John Vorster Square, however, retained and continued in its function as a police station, although renamed as Johannesburg Central Police station. The ownership of the building simply changed hands, from an authoritarian apartheid regime to a democratic and free post-apartheid system of governance. The bust of Baltazar John Vorster was removed and the building was given a new name. The name was, however, just a geographic designation in contrast to many streets and suburbs in South Africa which sought to replace apartheid conspirators with liberation struggle icons. In the turbulent decades that preceded the fall of apartheid and the decades post-apartheid, the building ‘endured’, it was never abandoned, burnt down, targeted or readapted like many other apartheid specific monuments. Unlike other sites of violent apartheid histories that were earmarked as significant contributors to apartheid memory, John Vorster Square and its inmates were largely side-lined from the narratives of apartheid memory.

“We don't remember the past. We were told that we must move on. We've reconciled, you know, the country is moving forward as a New South Africa.”

- Relative of an ex-detainee at John Vorster Square

Apartheid Debris

Police work takes place amongst the residue of the lives and deaths of many anti-apartheid activists.

BUSINESS AS USUAL

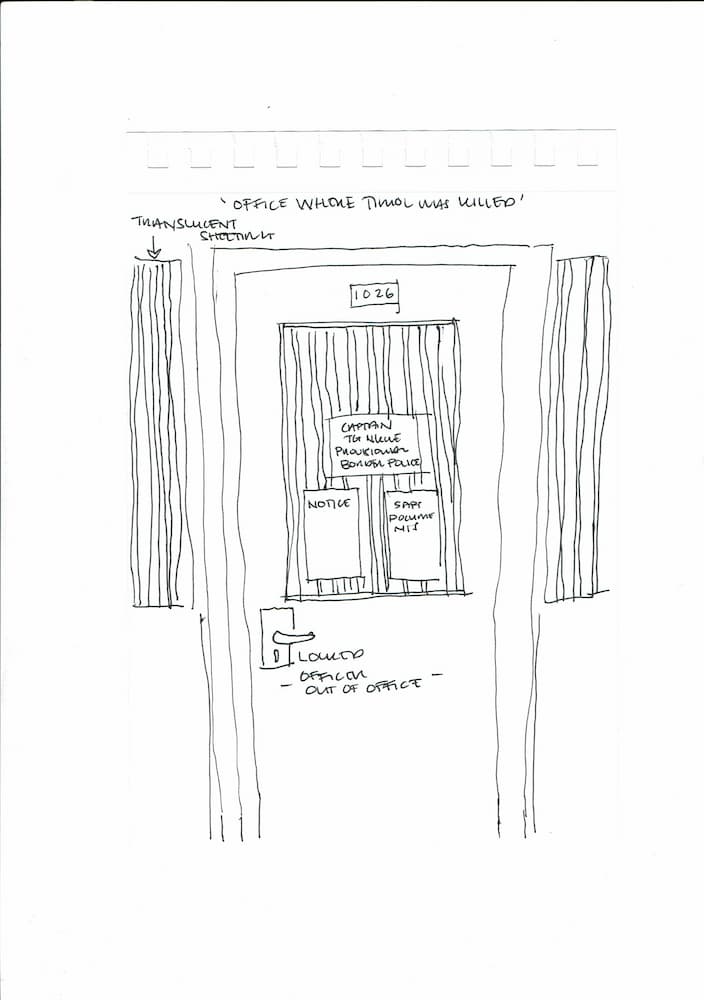

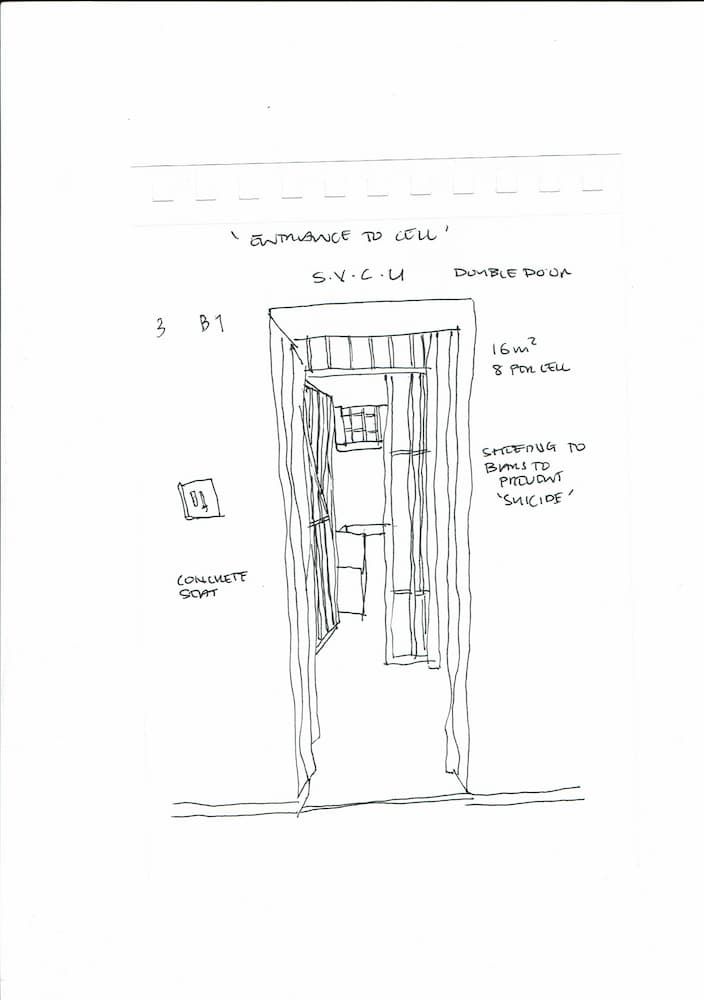

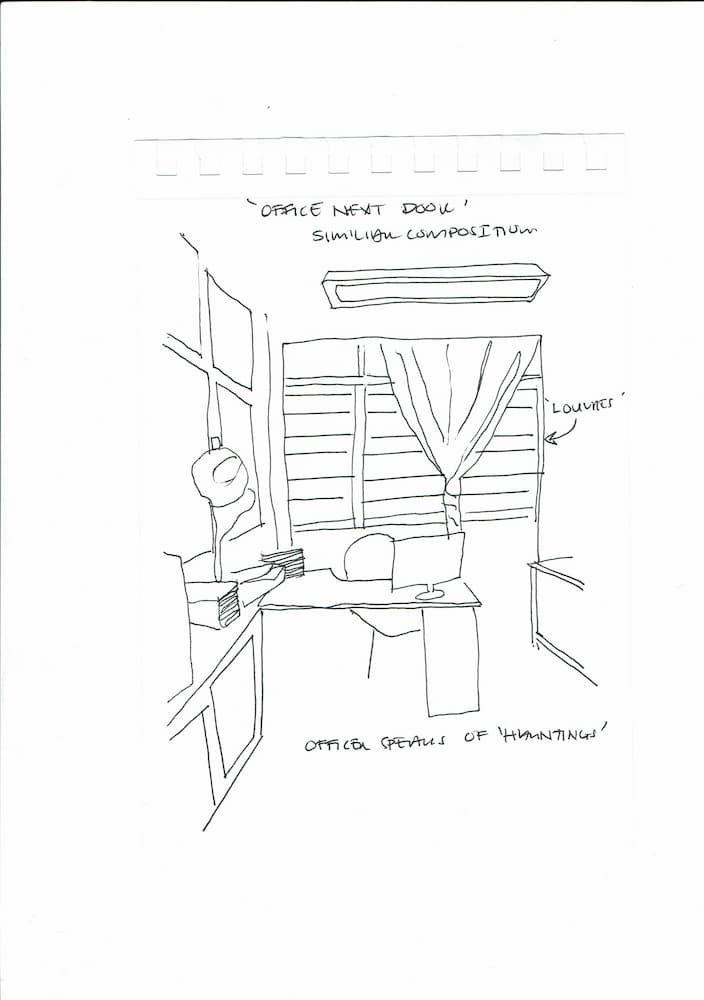

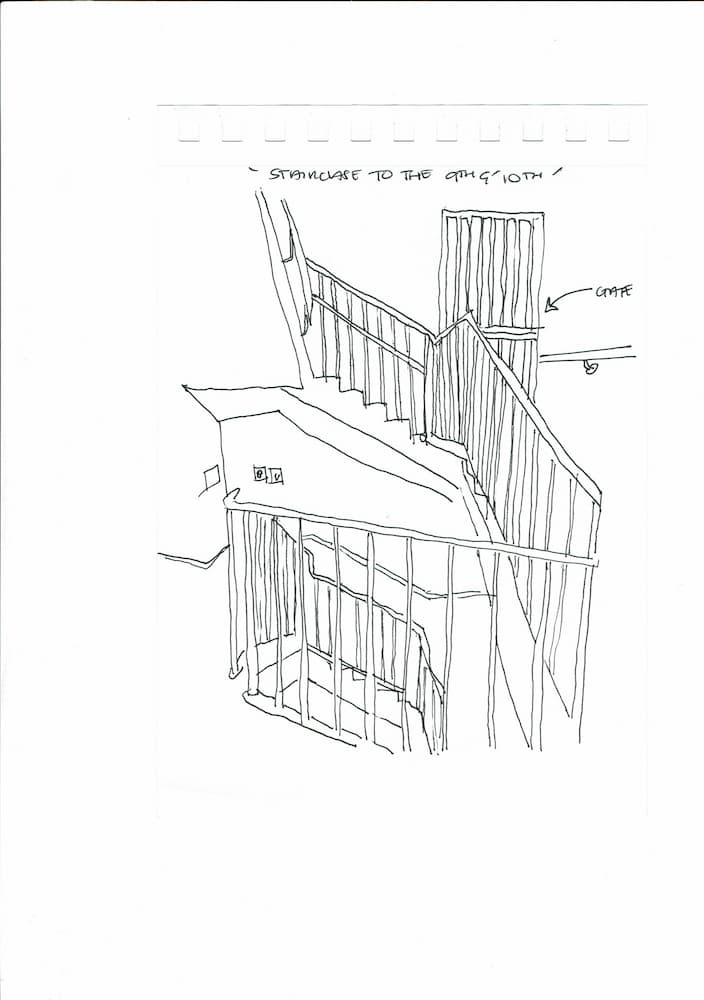

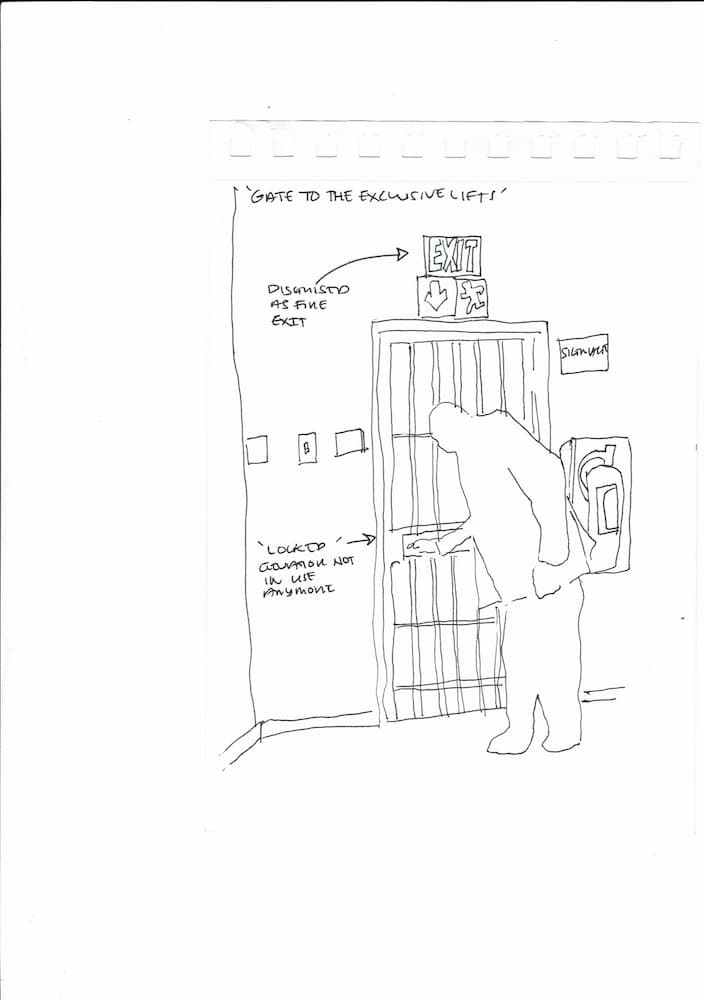

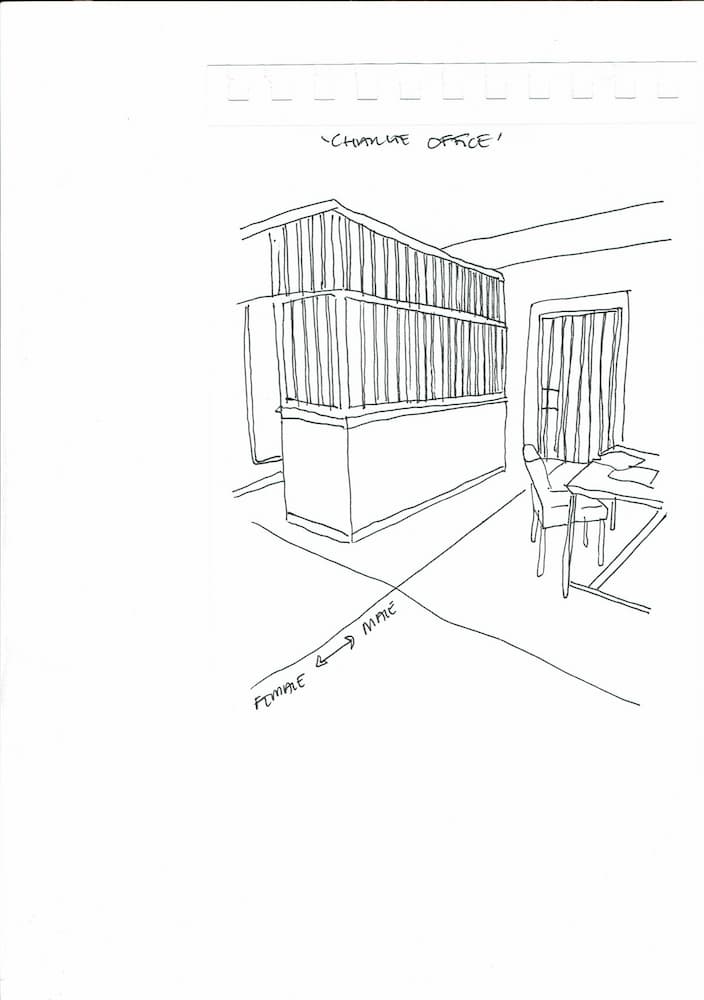

John Vorster Square was built at the height of the apartheid area, to serve as the headquarters for curbing anti-apartheid sentiment. It had isolated entrances, lifts and staircases for whites and non-whites, as well as strict separation between personnel and detainees held in the cell block. Today, everyday police work takes place within a structure built to serve the authoritarian regime, intimidate activists and eradicate anti-apartheid sentiment. Whilst some remnants of the brutal apartheid past like the bust of John Vorster were removed and the provocative name changed, the concealed entrance and lift that secretly carried people in and out of the building and strategically serviced the heavily securitised 9th and 10th floors, where anti-apartheid activists were tortured and murdered, still exists. Room number 1026 from which Ahmed Timol was thrown out of operates as an office and the cell in which Neil Aggett was hung is used for detention.

“It's hard to think that in the offices in which people were detained and tortured that people go about their everyday business. It's sort of conceptually and mentally quite weird to think of that.”

Architect involved in the inquest into Deaths in Detention cases at Johannesburg Central Police Station

DEBRIS AS HERITAGE

At Constitution Hill, material remains of apartheid brutality are preserved. The importance of retaining them within the new design of the site was emphasised by the Constitution Hill Steering Committee. All the buildings that comprised the Old Fort complex were retained except for the awaiting trial section which was partially demolished to make space for the Constitutional Court. The walls of the Constitutional Court itself are built using the bricks of the demolished awaiting trial block – ‘a symbolic act of recreating a site of democracy out of a site of oppression’ (Constitution Hill, 2024) – and a retention of the scars of imprisonment at the heart of post-apartheid South Africa.

Protests and Inquests

The public square in front of the Constitutional Court has been a space for protests and rebellion, concerts and entertainment, and a space for grief and mourning.

REPARATION

The Khulumane Support Group, a group of survivors and families of victims of apartheid conflict, has selected Constitution Hill to stage their protest in a bid to force the government to pay out long-awaited reparations. Their banners, often laid down or hoisted up between the ‘flame of democracy’ and the entrance to the court, forces where visitors and court personnel alike have to engage with them. The blankets, clothing items, food containers and other remnants used by the women who stay at the site for long periods creates a stark counterpoint to the sleek Constitutional Court building. Their actions highlight the ongoing grievances with the ineffectiveness of the TRC to deliver on its promises.

“... the ladies that are sitting there at the court challenging the non-implementation of the TRC recommendations to actually pay out (material) reparations for those that were affected by apartheid. [...] the site does lends itself out to such protest and such expressions.”

- Member of Management at Constitution Hill

DEATHS IN DETENTION

ANTI-COLONIAL SOLIDARITY

In 2017 the first inquest into the death of an anti-apartheid activist since the amnesty hearings at the TRC was held into the death of Ahmed Timol, who was killed at John Vorster Square. The inquest, held twenty years after the completion of the TRC, was the result of concerted advocacy and pressure by family members, lawyers and the general public. Since this first successful inquest, there have been other successful inquests and numerous other applications to the National Prosecuting Authority by individuals and families seeking legal investigations into apartheid era deaths in detention. Johannesburg Central Police Station is the site of one of the largest number of these inquiries and investigations into these deaths take place at the station on a regular basis.

The preserved cells at the Old Fort and the ‘Statue of Hope’ outside the Women’s Gaol are often dressed up, inscribed on, and protested in front of in solidarity with other freedom struggles – none more so than with the Palestinian liberation cause.

This is in addition to Constitution Hill’s ‘Palestinian Nakba Memorial Forest’ located at the Western edge of the precinct. This memorial honours the memory of the Palestinian villages that were destroyed and the people who were displaced in the Nakba (catastrophe).