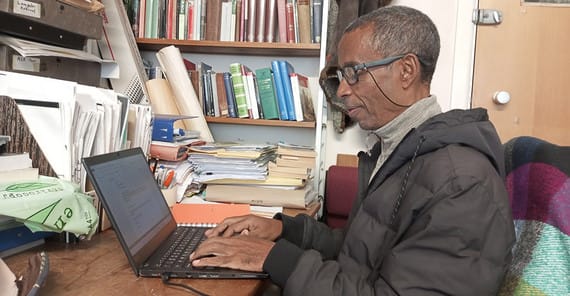

Meet Gerawork Gizaw

Gerawork Teferra Gizaw holds a master’s degree in development economics, a bachelor’s degree in conservation, and diplomas in law and business information systems. He has collected oral histories for Princeton University’s Global History Lab and won the 2024 Voltaire Prize for his contributions to social dialogue, international understanding, and tolerance. He has also worked as an academic coach, tutor, and learning facilitator for the Sustainable Development Program at Jesuit Worldwide Learning in Kakuma refugee camp.

Gizaw holds honorary research fellow status in the Faculty of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences at the University of Exeter. His past research areas include oral history, refugee life, education, hope, and hospitality. He is interested in research that involves historical investigations and systemic thinking related to human relationships, institutions, mobility, humanitarianism, education, business, environment, and development. He coauthored “Hope Disrupted: Refugees in Limbo” together with Dr Staci Martin, based on the Psychosocial Peace Building training she conducted in the camp. Currently, he is working as an academic advisor under a Jesuit Worldwide Learning (JWL) tertiary-level education program that offers associate and bachelor’s degree programs in collaboration with South New Hampshire University. His current research project focuses on exploring the evolution of human mobility and probing its implications for present-day laws and protocols related to “undesirable” forms of mobility.

In a virtual interview with the MBC team, Mr Gizaw discussed the legacy of detention centres in post-colonial Kenya, his work in the Kakuma Camp and the divide between community research and academic scholarship.

On Importance & Challenges of Working with Oral Histories

1. In one of your interviews, you mentioned that one of the greatest challenges is how your own experience reflects whenever you interview refugees. Is that always a disadvantage or does that help in the interview especially in helping the interviewee feel more comfortable in sharing their experience?

An advantage of being involved in research with lived experience (insider) is that, as you mentioned, it provides comfort and discussions can be freer; in addition, the language or communication barriers are limited compared to interviewing by outsider researchers. There are no as such constraints of time and place, as interviews can be done flexibly. It allows for deeper conversations with empathy, so when strong emotions are attached to the information, the emotions can be shared and lessons derived from it. Unrealistic expectations from the research or connections as a result of the research are also relatively limited as compared to expectations that arise as a result of research relationships with outsiders.

The challenge that I experienced (downside) is that questions might be framed in specific ways that highlight shared experiences, which could lead to deeper conversations, but also cause discomfort or guilt when I ask based on certain assumptions or questions indicate certain values or standards, or processes for that matter—since most survival means are stories that may contradict when discussed in different scenarios. Sometimes, they try to match responses to align with my understanding or beliefs; especially if they think I have more information or experience, like questions related to education, instead of sharing what they think responds with things like “you know better” with little details of their own views or experiences.

2. Critics of Memory studies allege that memories/first-hand accounts tend to be “fickle” and “heavy with emotions” which makes it an “unreliable source” for objective and academic research work. What are your thoughts on this notion? How can community researchers integrate their work in academic research? Or will this always be a separate field of study?

Stories (memories) with fickle and heavy emotions are unrealistic sources for objective research seems to me a biased statement that undermines context. Though the notion of objective research itself is vague in the context of refugee studies, “fickle and heavy emotions” are real in their own sense, and the study could start from there so that the entire research provides a situated knowledge. The problem comes when we ignore them and focus on something specific underneath as a result of a specific disciplinary interest or research requirements. To me, this is more of an ethical issue than purely research, as ignoring the general environments and being unable to link factors that cause fickle and heavy emotions to a specific research interest cannot provide complete information. Emotions and inconsistent information could be gateways to a deeper investigation.

Regarding integrating community research with academic research, considering difference in their objectives and the incompatibility of methodologies, I do not think there is a need to integrate them. Community level inquiry or research could be seen as a continuous chaotic process (learning through experiences) that has a local scope by its very nature, is holistic (not disciplinary). It helps to create awareness of contexts or solve local problems, not primarily aim for new knowledge creation or extension, though that could also happen in the process. – after all, not constrained or “disciplined.” However, the two can complement if the culture of community-level inquiry is restored, as it opens a door for academic research with lesser emotions and resistance.

The worrisome challenge that I learned from engaging in local level research is that the cause of flicking and unmanageable suppressed emotions manifest as a result of difficulty in accessing authentic memories (experiences) as local agencies have been overshadowed by the expectations of everything from various institutions, including academia, which intimidates by its systemic, disciplinary, and methodological sophistication and knowledge abstractions – a hidden but an is an iron curtain.

On Parallels between Detention Policies in Colonial & Post Colonial Kenya

3. The Museum of British Colonialism has documented the extensive network of detention camps used during the Mau Mau Emergency and other colonial periods. How do you see the spatial organisation and management of today’s refugee camps echoing or departing from these colonial precedents?

Colonial detention camps are formal places where people (groups) detained that actively resisted colonialism. So the detention was to either punish or deter resistance. The control was mainly physical, so they were physical carceral places; the punishment might have gone to a level of exterminations in the case of Zulus, in South Africa, who were taken to Cuban labor camps, in the earliest period of colonisation. Though it was barbaric but both sides had clear objectives to justify their actions more or less publicly. So, the detention centre was a place of struggle.

However, the current residents in camps are by-products (collateral damages) that were caused by “struggle” elsewhere, which is not clear to the majority. It does not mean that the conflict and insecurity they left don’t follow them, but it is a humanitarian camp. Most of the residents in the Kakuma context are minors who do not clearly define what encampments mean, and the other majority are women who mostly comprehend (have experiences) only the villages they missed. So, these contemporary camps are both symbols of care and control, but inherently different from colonial camps – if camps serve the ‘coloniality’, it could be in indifferent ways.

The problem with humanitarian camps is related to the liminal way of life of residents, mainly targeting to maintain life with a humanitarian support system that eventually disempowers and erodes agency. Unlike the colonial detention centres’ residents, who had their own agency (in the form of resistance), the modern camps lack agency. In the colonial detention centres, the suffering is more physical; in the case of modern camps, it is more related to psychosocial well-being. The relationship between detainees in colonial camps with detainers was more adversarial, which is logically accepted and manifestations of agency, whereas the relationship between refugees with humanitarian actors has been expressed in the form of saviours’ complex, that degrade camp residents to cases and numbers and alienate them from their agency, and relying on hope, while upgrading humanitarian actors and their collaborators to humble god and goddess. Since the humanitarian actors also sustain their life through providing these services and is difficult working towards the end of suffering – difficult to understand whether their humble goddessness is a real or a mask of modern coloniality.

4. What parallels, if any, exist between the legal frameworks that governed colonial detention and those that regulate refugee encampment today? How has international refugee law navigated this colonial legacy?

I have no information about the colonial regulations, but not difficult to guess, considering the barbaric nature, and it was meant to subdue. In the current humanitarian refugee management, there are international, regional, and national regulations that are appealing to humanity. But its applicability has been questioned in various ways. One of the intriguing principles that I bring here is the principle of “no regret basis” which is supposed to guide humanitarian actions to avoid any form of regret as a result of not responding properly or on time – the current crisis speaks to how hypothetical these principles.

I do not think these international and regional regulations encourage encampments in any way. It has been logistical reasons that have justified the case of mass forced migration. So the challenge in humanitarian encampment is the possibility of embracing those intriguing values and being humanitarian while institutions and their actors have personal and group interests that they bring into the humanitarian enterprises, one of which could be an extended colonial legacy or interest in a new form.

We may see the colonial legacy in the humanitarian agencies, as most of the humanitarian agencies are from the Global North, work across different continents, and are becoming means to negotiate for or impose interests. We can see this from the current US policy that tries to align aid policy with national interest, which is a regression to the past.

5. Kenya’s encampment policy has confined refugees to designated camps for decades. How might understanding this as part of a longer history of detention and spatial control in Kenya change policy conversations?

If my reading is right, the encampment policy did not emerge from Kenya as it has been a technology used elsewhere. Following the 1991 conflict in Somalia and Ethiopia, when the mass displacement overwhelmed Kenya, it surrendered the responsibility to UNHCR, and for logistical convenience, various camps were established and later reduced to two camps. However, the encampment policy has led to isolation in a harsh environment, perpetuating vulnerability. As time goes on, it could also create a space for a certain type of group identity to emerge and result in tension, which could lead to a potential for conflict and violent activities, not forgetting the violence that may also be imported from the place of feeling. Understanding this may help for more relaxed policy conversations against full or partial encampment, any other form of isolation, or something like that.

6. Colonial detention camps were often sites of violence that were deliberately obscured from public view and historical record. How is the documentation and visibility of conditions in refugee camps today similar or different? What barriers exist to transparency?

Colonial detention camps were a site of resistance and struggle (but not strictly in a sense of a site of violence), and formal documentation could not be expected like modern day – hiding crime could logically be part of the struggle from the colonial side. In the modern day, which is well-equipped and involves various institutions, such an expectation could be reasonable. So, it cannot be compared with humanitarian camps that are managed by multi-layered institutions. In modern days, there are various ways of documentation. But it should critically examine the objective of documentations (scholarly interest, raise funds, build institutions’ image, policy improvement, etc.) – who have access to them, to what extent they are detailed beyond numbers, how these documentations have contributed to reducing the number of refugees and camps, etc.

Especially when it comes to accountability, though the various humanitarian principles and standards are detailed and could help to ensure accountability, are there related data that regularly feed all these standards and indicators? Are there documentations that detail to inform the culture of accountability – are they available to the public, etc., are the question we need to ask. One good example may be the UNHCR data based – it has refugee and other displaced persons information in details since 1951 – which is somehow comprehensive and has helpful information for research – but considering the fact that UNHCR’s primary mandate is to save life – if consult the database for how many people died while in the camp – the database doesn’t provide answer – such type of information that leads to accountability need to be available.

Otherwise, the documentation serves mainly for image-building and fundraising purposes. Of course, there are barriers to implementing accountability, mostly related and procedural constraints. The multi-layered actors and complex institutional arrangements are another barrier. Besides, the different interests beyond humanitarian actions, including of those refugee producing groups and the possibility of being a truly humanitarian in a world maximising individual interest is the rational thing to do is another challenge that complicates accountability.

In general, the effort to compare the colonial detention centers with current humanitarian encampments seems a way to escape accountability through benchmarking a wrong context, which looks barbaric when looking back. However, however barbaric the past may seem, it was not as complicated and sophisticated as modern ‘humanity’ that could also become more dangerous or inhuman, not only the physical body but also the mind and soul, not putting people in physical detention camps, but through establishing sophisticated detention systems. For a person like me, who started looking back at history, knowing those ‘barbaric’ periods may help me appreciate some of the evolutions humanity made with all its shortcomings, but for children who are born in the camp and aspiring to learn, thrive, and live a normal life, such a comparison is utterly meaningless.

PS: Mr Gizaw would like to thank his team members Mcdonald Pala, Jacoub Mohammed Ali, Keth Aguin Marol, Romeo Joseph, Lucian Badodo, Alinoor Mohamed Omar, Ayuen Isaac Deng, Said Mohamed, Stephen Peter Kon, Nyan-Nyuei Majak Ador for the fieldwork pictures.