MBC’s Andrea Potts sat down with economic historian Jonathan Jenner to discuss the political economy of colonial Kenya and his current research on the spatial control of unemployment. Jonathan is based a the University of Manitoba and the University of Johannesburg.

Andrea: What do you research?

Jonathan: I’m interested in the specific mechanisms of the colonial political economy. So, I think about how economic value was generated in colonial contexts and the effects of this. Economic value was produced and captured in different ways across different colonies, and I think it’s important to pay attention to the specific mechanisms through which the economy functioned in specific contexts. This reveals a lot about the nature of colonialism, and the way in which it affects contemporary outcomes and possibilities.

I’m interested in Kenya. I lived in Nairobi until I was 10 years old, before moving to the States. So, it’s a place that I have a personal connection to. As a settler colony, colonialism in Kenya developed specific features which profoundly shaped its colonial political economy and, as a result, peoples’ lives.

A: So, what makes Kenya distinct?

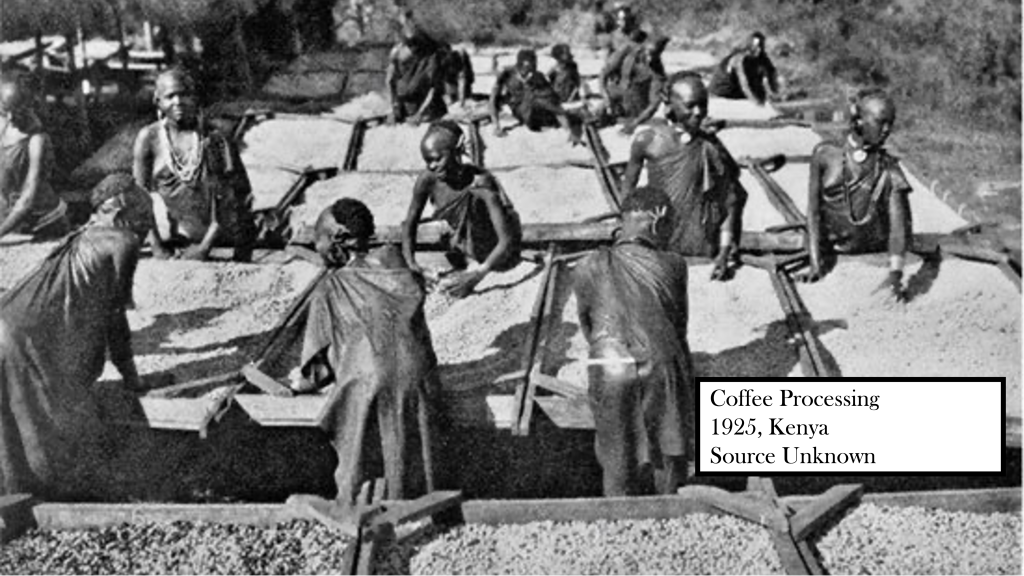

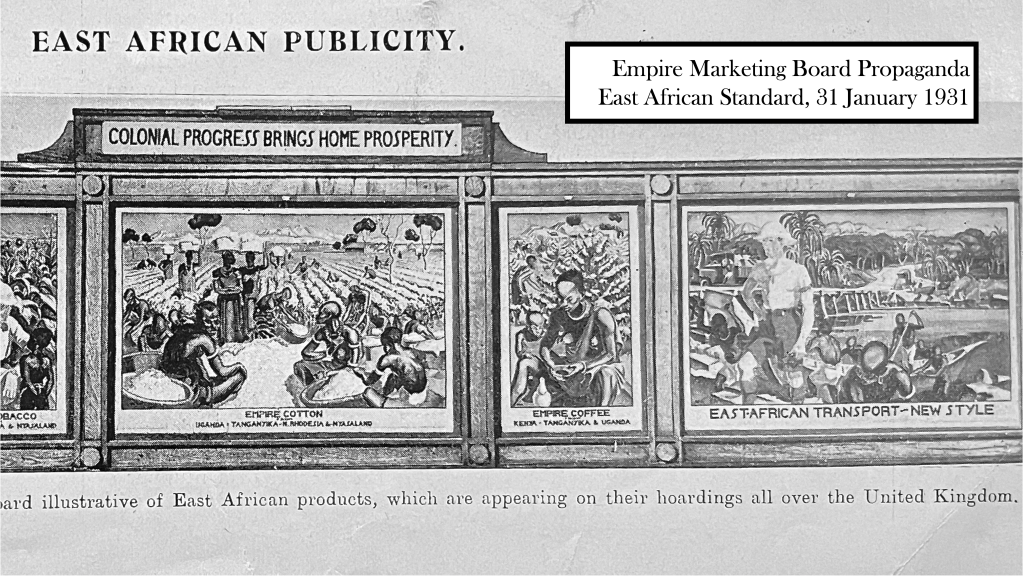

J: In Kenya, the British wanted to develop a plantation system. So, instead of looking for Africans to grow their own crops that they would sell to marketing boards, the British built a model of huge estates owned by settlers. This meant that the form of African labour that was needed was wage labour. And that meant that British colonisation in Kenya was primarily interested in getting a large number of Kenyans to stop growing their own crops on their own farms and to instead join a wage labour force. This was justified by the British as a civilised free market enterprise. It wasn’t forced labour like the system of the Belgians in the Congo. With a labour contract agreed to by employer and employee, no one is technically being forced to work, right? This idea of the liberal free labour market, couched in the idea of the ‘civilizing mission’ of colonialism, allowed Britain to hide a tremendous amount of violence that is necessary to make someone “voluntarily” come and sign a contract. The idea was to make forms of independent production less viable than wage labour, beginning with forms of land dispossession. So, the British essentially make a settler led plantation model, worked by wage labour the dominant model that supports export production in colonial Kenya. That sets Kenya apart from its East African neighbours.

They need to find ways to coerce Kenyans to become wage labourers, which involves trying to make livelihoods not based on wage labour more onerous and miserable.

A: So, what are the effects of this?

J: When the British show up and violently dispossess many Africans of their land, generally people were still able to farm somewhere, even if it wasn’t their ancestral land. No one wanted or needed to go work on the plantations of settlers. So, the British realise that they need to do more. They ask themselves: how are we going to get labour to show up? The obvious answer is to increase wages to encourage people to come, but farmers were not able or willing to pay wages that were high enough to attract Kenyans. So, they need to find ways to coerce Kenyans to become wage labourers, which involves trying to make livelihoods not based on wage labour more onerous and miserable.

A: How do they do that?

J: The first measure is something called the hut and poll tax. This was a direct tax on all African working age males. And it forced these men to find surplus cash somehow, and not just any cash, you need East Africa shillings. There were several ways to do this – you could grow and sell your own crops, but it created pressure to sell your labour. If you did not pay, you went to jail. And the police can stop you at any time and demand that you produce your tax receipt. But this still wasn’t enough, and the British brought in more measures. For example, they made it effectively impossible for Africans to grow cash crops, such as coffee, tea, and pyrethrum. And they introduced the Native Reserve System, which meant that many more Kenyans were dispossessed of their land, which became crown lands. The ‘crown lands’ became known as the White Highlands, and Africans were pushed into living on the ‘Native Reserves. Increasing the population density in the Native Reserves made it much harder for Africans to grow their own crops and therefore pressured them to work on settler estates. There were a whole host of other measures brought in too, such as passbooks which restricted movement. All of these measures were making anything that’s not wage labour miserable and eventually untenable for enough people who would staff the European estates.

This system started finally working by the late 1920s. And when I say working, it was a highly dysfunctional system for Kenyan society, but it’s working for the settlers’ demand for labour. But the stock market crash of 1929 meant that demand overseas for Kenyan export goods decreases, and prices fall. And Kenya finds itself in a position where workers are being laid off. And for the first time in 30 years there’s more Africans looking for work that can find work. This changes everything, and it’s where my own current research really starts.

A: So, what’s happening in the 1930s?

J: For unemployed Kenyans who had been working on the estates, there were now not many other options, as those had all been effectively removed by the colonial institutions which pushed them into the labour force. So, there is massive unemployment, and because of the particularities of the Kenya colony, it’s persistent. It sticks around for a while. It’s structural, and it’s very widespread in all different parts of Kenya. And on the one hand, settler farmers love unemployment as it pushes wages down. And wages do drop. But the problem was that settlers were also terrified of unemployed young Black men. They fear that white women will be attacked, they fear that they will be burgled. And of course, these fears are sensationalised and racist, and they don’t match reality, which is that crimes against persons and property had no appreciable rise in the 1930s. Settlers also feared that unemployed men would join unions and political organisations to organise against them. I also think that on some level, the fact that there would have been large numbers of folks looking for work, wandering from farm to farm, undermined the idea that the colonial economy was working for all and that the British knew best. And what I look at the response of the colonial state. I look at how the Kenyan police were deployed in a new way in the 1930s to manage the situation in a way that served settler interests.

A: So, what role did the police take on? And how did settlers want to control Africans in Kenya?

In the 1930s, settlers were very happy to maintain a high level of unemployment to keep wages low. But they wanted to control the movements of unemployed Africans and keep them segregated.

J: In the 1930s, settlers were very happy to maintain a high level of unemployment to keep wages low. But they wanted to control the movements of unemployed Africans and keep them segregated. And they come up with a huge amount of laws and municipal codes to be able to pick people up and move them to elsewhere in Kenya. The obvious example is vagrancy. So, not having a job in the first place is sufficient to arrest someone. And the very important thing that happens is they are not interested in incarceration. They’re not interested in locking up and holding young Africans in jail. It’s like, I pick you up, I take you to the magistrate, I don’t even care what the magistrate says. You’re guilty, not guilty, either way. Just the fact that you’ve been picked up by the police and then you see the magistrate means that you’ll then be transported back to your reserve. And that accomplishes the structure of ‘I want you unemployed, but I want you unemployed over there.’ But some of the other laws and municipal codes, beyond vagrancy laws, are wild. Like loitering in a traffic island and misuse of a bicycle.

A: What’s the strangest example?

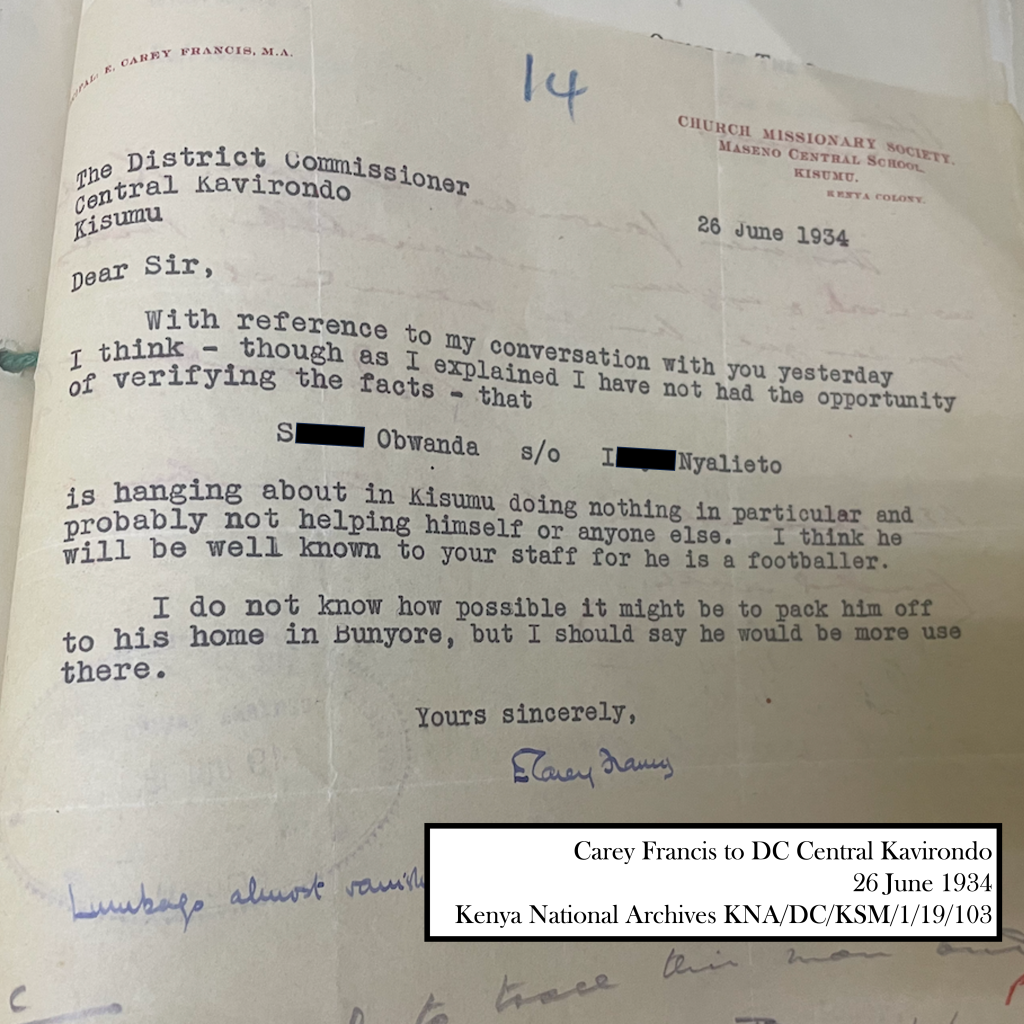

J: in 1933, the Kenya colony passed ‘The expulsion from certain areas of the colony of persons whose presence therein is deemed to be undesirable ordinance’. So, someone could just be declared undesirable, and then you have to leave and go to your reserve. And it’s only a criminal conviction if the undesirable person doesn’t leave. So, we have no idea how many people were really moved. So much of this was not recorded.

Someone could just be declared undesirable, and then you have to leave and go to your reserve. And it’s only a criminal conviction if the undesirable person doesn’t leave. So, we have no idea how many people were really moved. So much of this was not recorded.

A: What sources are you using and how much work did you have to do to uncover this? Was it all very explicit, or did you have to ever read between the lines?

J: There is material at the National Archives in London and at the Kenya National Archive and the Macmillan Library in Nairobi. When I started this research, I was looking for something far more straightforward. I don’t think anyone could have been looking for this story. I was looking at letters between farmers and local district commissioners, and I started to notice patterns. Like, the word undesirable is being used a lot. And then when I saw the ordinance, it really hit me. And some examples really whack you in the face when you find them! For example, there’s a guy called Carey Francis, who writes a letter to the district commissioner. He says that this young man is hanging out in Kisumu doing nothing and that he is probably known to your staff because he is a footballer. He says, I don’t know how it might be possible to pack him off home and adds that ‘he would be of more use there.’

Some examples really whack you in the face when you find them!

A: The reference to the football. How chillingly specific.

J: It’s incredible. And it kind of sounds like this guy wanted him removed because he was playing soccer! That’s his crime.

A: And while it’s highly personal, he also has this structural system in place that allows this, right? That you could write to the district commissioner.

J: Exactly, and once I started seeing this, then I started seeing it everywhere. But it took a very long time. The final piece, though, is making sure, once we’ve taken all these unemployed people and we’ve dumped them in the reserve, how do we make sure they stay in the labour force? And one of the ways was to use district commissioners to work as recruiters, effectively. They would move people around in line with what labour was needed where. You could write to him and say: I need 50 men to work on this sugar estate at this time. And he makes it happen.

People who are just trying to scrape by in any kind of informal way, i.e. they aren’t making profits for others, are subject to constant police harassment. I don’t think that’s a coincidence. I think there are important linkages to the past structures in the colonial economy of Kenya.

A: What are the traces of this today?

J: The first is inequality, and particularly land inequality. Land inequality is one of the underlying mechanisms of this and it continues post-independence, just with a lot of land moving hands to African elites. And broadly, you can see forms of labour coercion today, obligating people to sell their labour power, and pushes down wages for the export sector. This is particularly clear in the structure of Kenya’s flower export industry. And we can see legacies of this history in the role that the Kenyan police force takes on. Less focus on their professed commitment to ‘law and order,’ and a consistent commitment to protecting profitmaking and elite society. People who are just trying to scrape by in any kind of informal way, i.e. they aren’t making profits for others, are subject to constant police harassment. I don’t think that’s a coincidence. I think there are important linkages to the past structures in the colonial economy of Kenya.