Part One - The Rainforest

One of the biggest fallacies in the history of botany is that plant discoveries were the heroic achievements of individual explorers. Yet the role of indigenous knowledge is consistently written out of these stories.

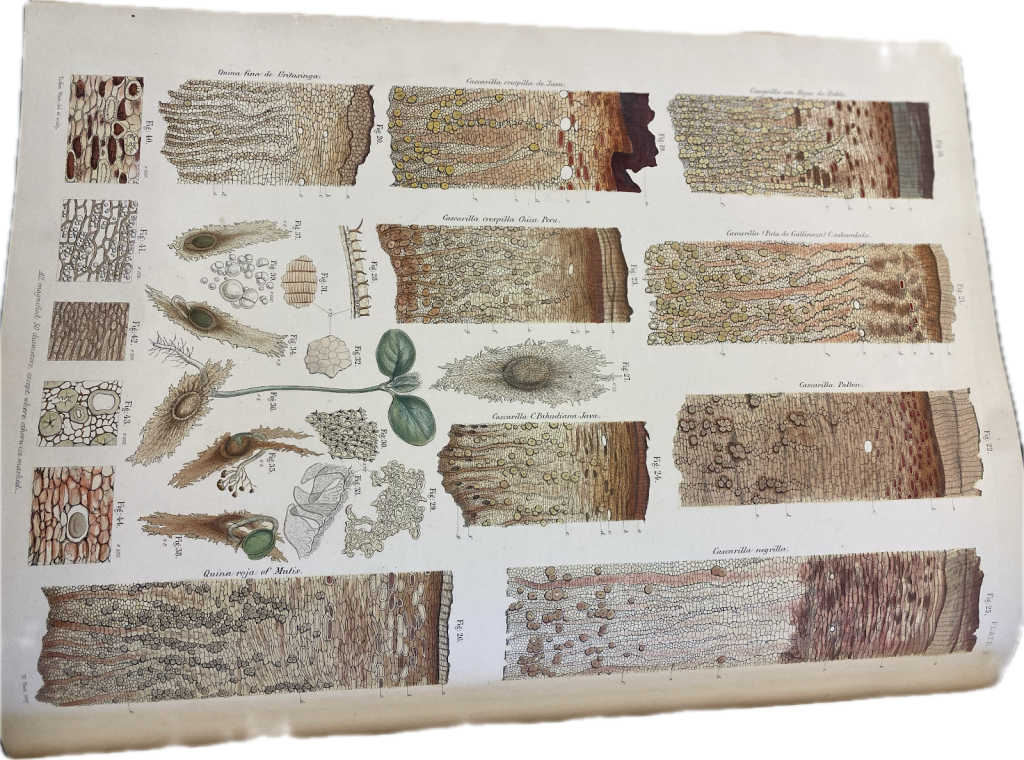

Quinine is widely known as an anti-malarial drug that propelled the growth of British imperialism into Africa, India, Burma, Ceylon and Malaya. Initially these places had been too dangerous to send colonists due to the disease. However, the story of how quinine was acquired from the flowering plant cinchona is often forgotten or misunderstood. This is largely because we only recognise it in its product form, quinine, rather than in its plant-form.

Plants and stories of empire are deeply intertwined as they were frequently used as commodities to fuel colonisation. During this process, indigenous knowledge of plants was frequently suppressed. It was suppressed through unequal power dynamics. This three-part blog series explores what the interactions between plants, indigenous communities and colonial powers can tell us about empire. It aims to retrace the role of indigenous knowledge in histories of botany, with a focus on the entanglement of human-plant relationships through the global transfer of quinine as it moved across three different places: the rainforest, the botanical garden and the plantation.

The Botanical Explorer

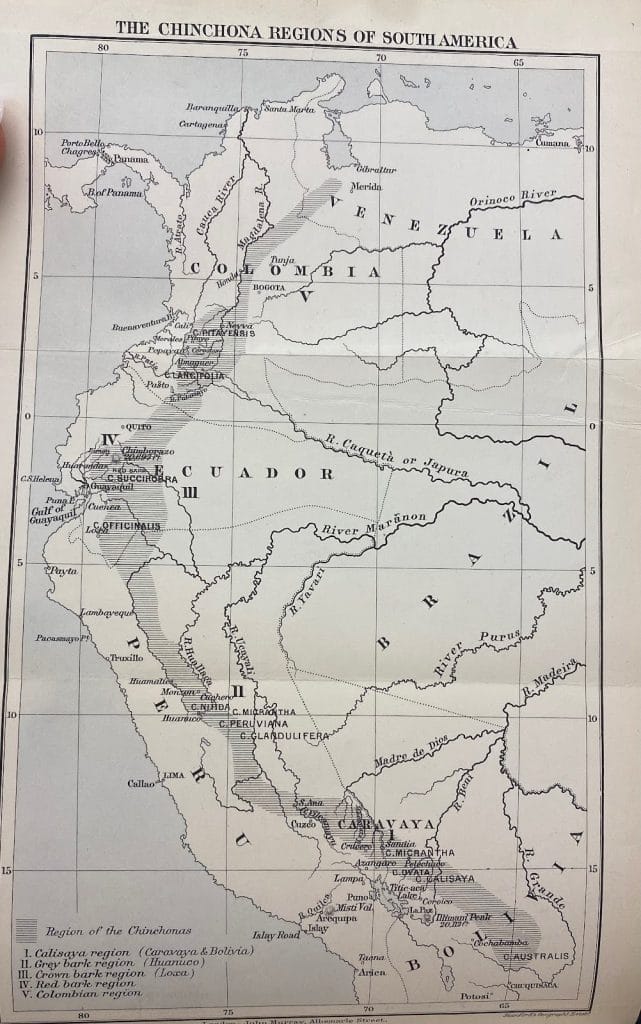

On 12th July 1849, the botanical explorer Richard Spruce embarked on his expedition to South America, as commissioned by Her Majesty’s Secretary State of India. He hoped to procure the Red Bark genus of the quinine-producing cinchona tree. In 1858, Spruce reached Ecuador where he made a base at Ambato for three years and procured seeds from Red Bark cinchona trees. Although one of the lesser-studied botanical explorers, Spruce’s success resulted in the mass establishment of Red Bark plantations, the highest quinine yielding variant of cinchona, in British India and Ceylon that propelled the sale and distribution of this tool of empire.

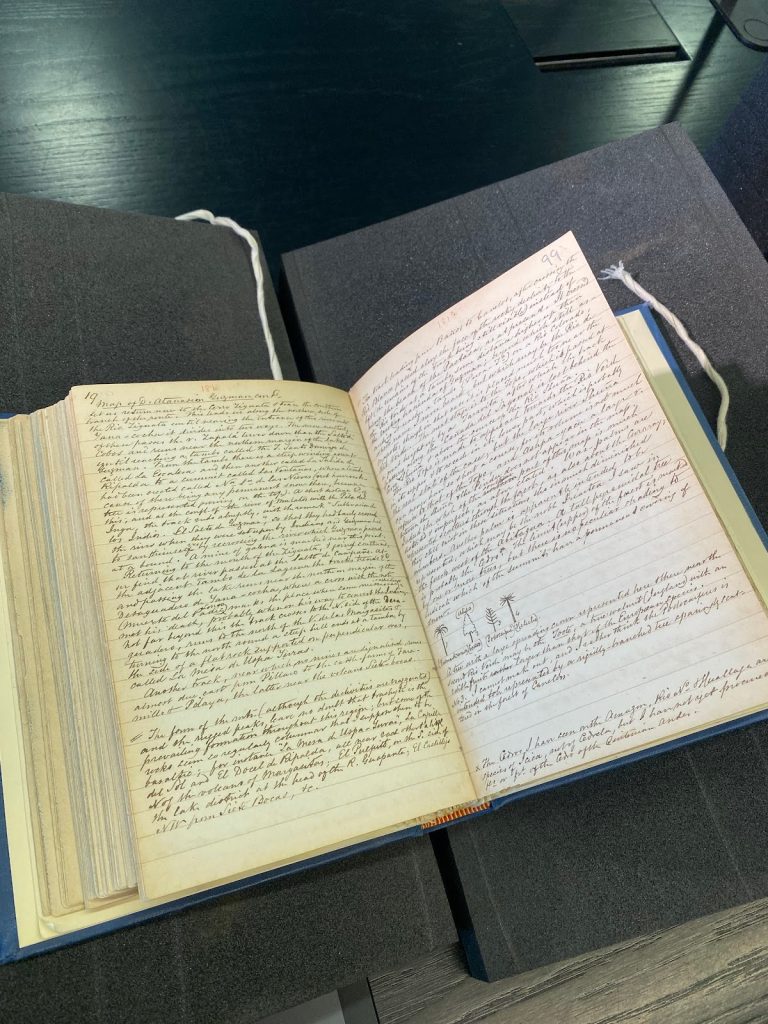

Richard Spruce’s journals and the ‘cinchona collections’ at the Royal Kew Archives are part of its Miscellaneous Reports Project, some of which have only recently been catalogued for public and academic use. Many of Spruce’s letters and journals that I explore here remain uncatalogued – which definitely tested my skills navigating the archives. The main aim of the Miscellaneous Reports Project is to list around 700 volumes on the movement of plants and botanical knowledge between Britain and her colonies from 1850-1928. I am very interested in how Kew Gardens is taking a growing interest in ethnobotany – how different countries or regions made particular use of plants. Whilst Kew Gardens’ colonial past cannot be forgotten (as I will explore in the second blog), research into ethnobotany will help support biodiversity consideration and the revival of indigenous cultures.

If I asked you to describe a botanical explorer, you’d probably imagine a quirky Victorian-era adventurer wearing a pith helmet, khaki clothing and carrying leather notebooks and specimen jars. Of course, we are fed this archetype through historical fiction and adventure movies with protagonists who discover lost cities or civilisations. I find the term ‘discovery’ in any colonial context problematic because it assumes that it was the achievement of this singular person, and that the item of discovery did not exist in any other culture beforehand. As I’ve learnt through my research at Kew, the ‘discoveries’ by botanical explorers were based upon observation of indigenous use of plants in their native environments.

I realised that this classic image of the botanical explorer is very much framed around the culture trope of the rainforest or ‘tropics’ as “untouched” by civilisation – ancient, wild, magical and home to venomous animals, sweltering heat and a sense of disorientation. We then have the intrepid explorer who dares to venture into them in search of a lost treasure. This trope expands to Indigenous communities of the rainforest, who have often been portrayed as ‘the exotic’ of ‘the savage’ in colonial tales that oversimplifies their cultural practices.

This is why ethnobotany is so promising because it places emphasis between various cultures in sharing knowledge on plants, and considers the ethical issues of creating products (such as quinine) from plants (such as cinchona) without the acknowledgement of Indigenous communities.

The Indigenous Use of Cinchona

Unlike other botanical explorers, Spruce fully immersed himself in Quechan and Andean Indigenous cultures and languages, receiving no outside correspondence during his tenure, and can be seen as one of the earliest botanical anthropologists. Spruce’s assignment was to essentially procure samples of Red Bark that could be sent back to Kew Gardens. He also observed how cinchona was grown in its indigenous environment so that these systems could be mirrored on a mass scale in British cinchona plantations in India. I was interested to answer two key questions from Spruce’s cinchona collections. What uses did Indigenous peoples of the Andes (now Peru, Ecuador and Bolivia) have for cinchona and what role did they play in Spruce’s “discovery”?

It is understood that the Indigenous people of the Andes were the first to use cinchona bark for its medicinal properties, long before Europeans, particularly for relieving fevers by chewing on the bark. These traditional uses were first observed by Spanish colonists in the 17th century who popularized its use in Europe as “Jesuits bark” or “Peruvian bark.” There are no written records created by Indigenous Andean peoples themselves detailing early use, as their cultures relied upon oral traditions. Therefore, when read carefully, documentations of Indigenous use within colonial records, including Spruce’s archives, pose huge potential in recovering these histories.

In Spruce’s 1861 report to Her Majesty’s Government, where he comprehensively detailed his three year tenure in Ecuador (1859-1861), Spruce dismissed the Andean’s knowledge of the medicinal properties of the cinchona tree. He wrote that when he had explained to the Andeans that Red Bark ‘yielded the precious quinine’ they suspected that he had ‘stuffed them with a tale’ and they were ‘tricked by foreigners.’ This skepticism, Spruce suggested, underscored the deep mistrust between indigenous communities and European outsiders, widened by centuries of exploitation and misunderstanding. It also suggested to the government that the Andeans themselves were unaware that the bark of their native trees contained quinine, the very compound driving foreign interest in their forests.

Spruce’s journal ‘Notes on a visit to the cinchona forests on the western slope of the Quitenian Andes’ details his time spent in smallholding farms, which the settler elites had a monopoly over due to regional political instability. Spruce wrote that the Red bark was often sauntered for firewood so much that ‘squatters, once knowing the value of the bark, had taken hold over the clearings.’ He clarifies this perceived ‘value of the bark’ as economic, not medicinal. Spruce recounted that a man named Toscano, whom he identified as one of the ‘primitive settlers in Limon’, told him that ‘Red Bark was very abundant there thirty years ago, until settlers found it made excellent firewood so they cut it up for that purpose.’ Following this revelation, ‘15 years later, a bark dealer came to Limon from Cuenca who offered the locals a dollar for every tree they showed him.’ The bark was of no value to the locals, as they had sufficient firewood, and the dealers received ‘500lbs of bark for 1 dollar.’ Other dealers followed, and by the time Spruce arrived, Toscano told him most of the Red Bark trees had gone.

The depth in which Spruce observed and recorded Andean cultures and languages during his travels makes it difficult to understand how he wouldn’t have learnt of the traditional uses of cinchona. He took a fascination in their rituals and ceremonies and his journals offer a valuable insight into these practices. Thens why did Spruce propel the narrative that the Andean people did not use cinchona for medicinal uses? He stated that it went against their traditional knowledge system of using contrasting hot and cold ailments for illnesses. Perhaps he wanted to report back to the British government that he had discovered the plant himself? His journals include an etymology of over 21 local dialects that he encountered in the Amazon, as well as the contributions of local communities (albeit indirectly inferred) whose histories are frequently undocumented in traditional archives. Studying the contents of Spruce’s etymological chart, where he translated over 76 words across 4 different Amazonian dialects, reveals the types of conversations he held with Ecuadorians. The majority of these relate to navigation and simple conversation as well as botanical terms. This reveals that building familiar or working relationships with indigenous inhabitants were key to procuring his specimens, further suggesting a more collaborative dynamic than is attributed in the official record.

Indigenous Intermediaries

Spruce’s voyage through the Amazon was undoubtedly arduous. It included a 14 week journey by canoe up to the Postado to Canelos in Ecuador. Yet, what is less known in official reports, is that Spruce experienced a period of ill-health whilst in the Amazon and suffered heavily from the effects of rheumatic fever. In 1849, Spruce thought that his bronchial trouble might be tuberculosis, and he wanted to see a tropical rainforest before it was too late. Whether or not linked to his health, Spruce’s task undoubtedly required a degree of collaboration with Andean people to navigate the unchartable terrain, impart local knowledge and mediate political tensions in the Amazon. This collaboration can be understood as the role of indigenous intermediaries, a crucial role in discovery narratives that are being retraced.

Spruce’s journals feature the names of certain local individuals who were fundamental to his success in procuring Red Bark. Although they are not credited by Spruce (nor acknowledged in any official documentation) revisiting these sources with ethnobotanical methodologies helps relocate their agency within botanical history. The first indigenous intermediary that can be traced is a man named ‘Bermeo’ who Spruce procured as a guide on his third day in Lumas. He was described as an ‘honest and active fellow’ who told Spruce that the Red Bark was located a three day’s journey into the Amazon from Lumas if they were to find it at any quantity. Spruce also described how Bermeo and his ‘companion’ would travel deeper into the rainforest from their camp, and climb trees to cut bark samplings. Bermeo is the only named intermediary, but there are casual references to people who offered crucial assistance to Spruce in his journals. For example, he wrote of ‘Indian helpers’ who had to build bridges to cross streams in floods.

Another issue for Spruce was that many of the forests known to grow Red Bark were private property and sat in disputed areas between Ecuador and Peru, with strict laws against plant smuggling out of these areas. This would have undeniably required a degree of litigation with the owners of these forests as well as social connections within these communities. Spruce wrote of making friendships with two men named Dr Najera and General Flores who owned forests and gave him permission to take barks and plants. For a payment of $400, Spruce was allowed to take as many seeds and plants as he wanted (but was not allowed to touch the bark) and Dr Najera also agreed that whilst his farmers were procuring bark, they could collect seeds for Spruce.

Framing the exchange of cinchona from Andean communities and its environment to Richard Spruce helps us to understand how it functioned as a collaborative partnership. This forces us to ask fundamental questions of the ways in which we remember and retell histories of botanical exploration. I would be interested to find out how the role of indigenous intermediaries could be traced in the narratives of other botanical explorers. This asks us to redress narratives of agency and ownership in histories of botanical discoveries. Through placing ethnobotanical methodologies on Spruce’s journals, it is clear the indigenous communities played both a role in procuring Red Bark for it to be taken back to Britain, and that their knowledge surrounding the procurement of cinchona was taken and then reproduced in different environments.

Written & researched by Esme Barrell

The next blog will focus on what happened to cinchona when it reached Kew Gardens, and the role of the botanical garden network in both British imperialism and the appropriation of indigenous knowledge on plants.

Bibliography

Miscellaneous Reports Collection, Archives of the Royal Botanical Kew (London)

- Journals of uses and Amazon plants c1860s

- Journals and uses of Amazon plants c1850s

- Correspondence 1832-1934

- John Eliot Howard, Illustrations of the New Quinology of Pavon, 1862

Ah, Richard Spruce, truly a master of both plant-collecting and narrative revisionism! Its fascinating to see how meticulously he documented Andean cultures yet seemed to conveniently overlook their deep knowledge of cinchona. His journals are a treasure trove, revealing a man utterly captivated by indigenous rituals yet somehow failed to grasp their medicinal insights – perhaps to better frame his own discovery for the British government? The role of indigenous intermediaries like Bermeo is often understated, yet they were clearly essential. Its a reminder that the discovery narrative often masks a complex web of collaboration and existing knowledge, challenging that charming pith helmet archetype. Definitely makes you appreciate the efforts of modern ethnobotany to set the record straight!quay random