Part One - Kew Gardens

This project began with a single plant. While researching in the archives of the Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew, I came across a set of cinchona specimens – delicate strips of barks, pressed and labelled in neat Victorian handwriting. They were part of the collection deposited by the English botanist, Richard Spruce, who returned from South America in the 1860s carrying what would become one of the most important plants in Britain’s imperial history. Many can be drawn into the romance of exploration, such as Spruce’s arduous journeys through the Andes and the life-saving potential of quinine. But as I looked deeper into how Kew Gardens curated, classified and displayed cinchona, I realised this was not a story of scientific triumph. It was also a story about the appropriation of Indigenous botanical knowledge into the British imperial network. This continues to impact how Indigenous understandings of healing and the use of plants were redefined in Western scientific systems, often without consent or recognition.

In many ways, this research made me rethink the places I’ve always loved visiting. I’ve had countless visits wandering through botanical gardens (Kew among them) simply enjoying the glasshouses and sense of calm they offer. I also remember visiting the Tropical Spice Garden in Penang, Malaysia, but not seriously considering how such spaces are connected to colonial histories of trade and extraction. Botanical Gardens, I realise, are not just sites of learning or leisure, but living archives of the empire.

Continuing with the story of cinchona and Spruce’s collections, this blog explores how Kew Gardens became a key site where Indigenous knowledge from the Amazons was institutionalised and exhibited as part of Britain’s vision of empire. It explores how our contemporary encounters with these gardens are still shaped by that past.

The Imperial Garden

In 1862, Richard Spruce returned to Britain from South America with cinchona specimens and bark – the so-called “Red Bark” or Cinchona succirubra. These were deposited at Kew Gardens, where botanists and chemists worked to identify and reproduce them.

By the mid-19th century, Kew had become far more than a leisure garden. Under the Directors Sir William Hooker and his son Joseph Dalton Hooker, it evolved into a world centre for botanical imperialism. This meant that it linked London’s scientific elite with natural resources taken from Britain’s colonies. Plants and knowledge flowed into Kew from every corner of the empire: tea from China, rubber from Brazil, breadfruit from the Pacific and cinchona from the Andes. These were then sent out to other colonies or plantations and allowed Britain to sustain her empire. Quinine from cinchona plants protected soldiers in regions where malaria was rife, just as tea, rubber and spices were mass-produced elsewhere to be sold for high profits. Kew’s role was partially practical, such as developing and testing plants, but also symbolic to show Britain’s mastery of nature to visitors from home and abroad.

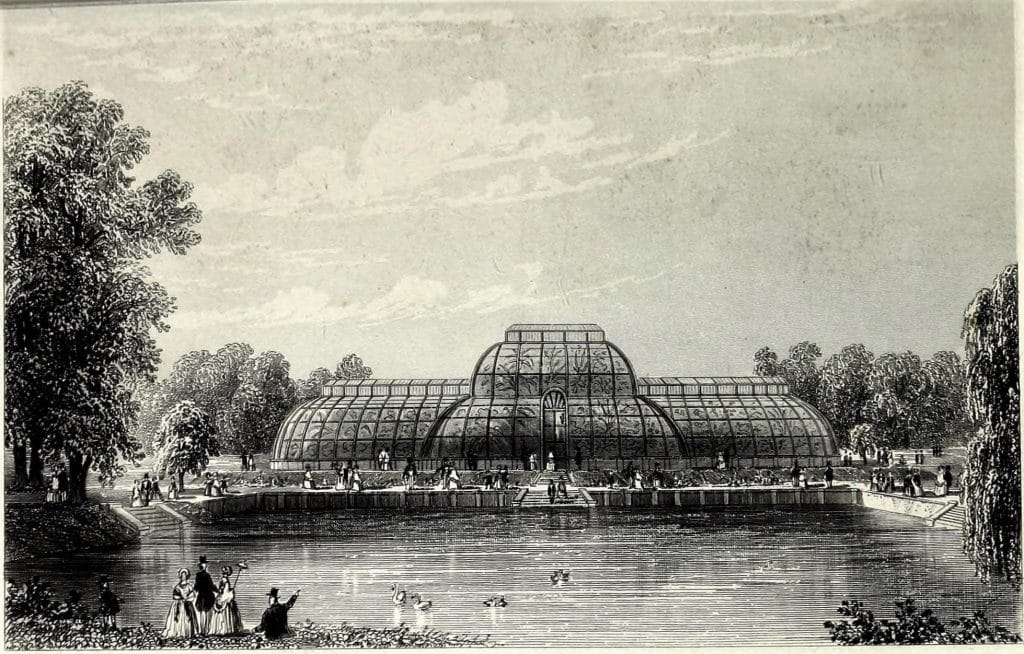

Kew very much became a showcase of empire. In 1863, the newly constructed Temperate House at Kew opened its doors to the public. The vast Victorian glasshouse, one of the largest of its kind, was a symbol of Britain’s global reach and a place where the public could visit tropical plants tamed within an English landscape. When I saw engravings of the Temperate House from the period, what struck me was the deliberate blending of science and spectacle. These were carefully managed environments, a ‘calculated space’, as historian Londa Schiebinger puts it, where tropical plants were made to appear civilised. The danger and wildness that people associated with the “tropics” had been domesticated into what feels like a museum of empire.

Naming as Ownership

For me, one of the most revealing aspects of this story was the language used in naming and discussing cinchona within these glasshouses, which functioned as laboratories as much as gardens. Kew’s scientists used the Linnaean taxonomy, the classification system that continues to divide plants into neat hierarchies of genus and species.

Cinchona succirubra, the Latin name for Red Bark, replaced its local Andean names like ‘cascarilla colorada’ or ‘quina-quina.’ Indigenous knowledge about the tree’s healing properties was absorbed but rarely acknowledged. Instead, scientific Latin gave the plant a new identity that fit comfortably within European systems of thought. In other words, to name the tree was to claim it and remove it from its local context. Even the small labels (still used) in Temperate House, intended for public visitors, reinforce this authority and the language is factual and devoid of local meaning. Ultimately, the practice of naming is a form of ownership and to assert control.

In the Andes and Amazonian forests, cinchona has been used by Indigenous communities for centuries. Local healers (Quecha, Aymara and others) knew exactly which trees to harvest and how to prepare the bark to treat fevers. The knowledge of these trees is ecological and cultural all at once, embedded in local systems of care and belonging with nature. In contrast, when I visited Temperate House, the knowledge of the people who first used these plants was missing.

This naming was also tied to hierarchy and value, as not all cinchona species were considered equal. Unlike other species, the Red Bark that Spruce brought to Kew had the highest quinine content, making it exceptionally valuable for commercial production. Its potent alkaloid levels made it a botanical treasure whose control could mean life or death in tropical colonies.

The Science of Control

I learnt that at Kew, cinchona became the subject of intense study. Botanist John Eliot Howard, one of the world’s leading quinologists, published Illustrations of the New Quinology in 1864. These were a series of detailed studies and hand-coloured drawings based on various species of quinine.

For Red Bark, Howard’s illustrations didn’t just represent the plant, they advertised its uniqueness. It was presented as superior to other species, both scientifically and commercially. These highlighted the tree’s distinguishing features: deep red bark, flowers and seeds to emphasise its superior alkaloid. The combination of visual precision and scientific text served to advertise Red Bark’s scientific and commercial value.

While other European powers imported cinchona bark from South America, I was interested to learn that Britain was the only country to collect and cultivate living specimens in botanical gardens like Kew. Britain essentially domesticated the plant outside of its native environment to ensure a steady supply of high-quinine trees under imperial control. This process became a symbol of the empire’s ability to harness and control nature.

The Afterlife of Empire: Kew’s Plant Archives

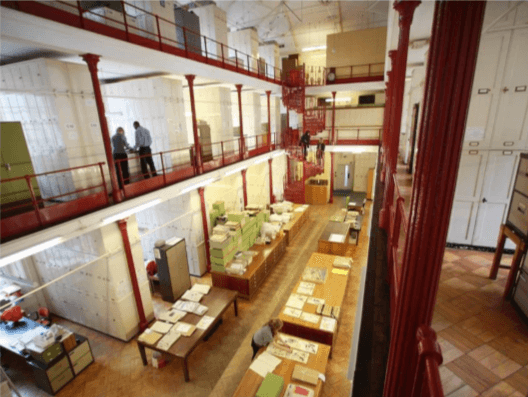

What fascinates me is how these histories still live within Kew today. Spruce’s Red Barks specimens are preserved in Kew’s Herbarium, alongside more than seven million dried plants, a global archive of nature and empire. Holding one of these sheets in my hands, I realised it wasn’t just a fragment of botany but a piece of imperial debris. As the anthropologist Ann Stoler writes, these objects are the residues of empire: material things that continue to shape our present.

These specimens, originally collected to serve the empire, now underpin conservation and biodiversity research at Kew. Scientists use them to trace plant origins, identify endangered species and understand ecological change. But even as they contribute to global sustainability, they carry with them the traces of scientific knowledge entangled with the legacies of colonialism.

Reckoning with the Past

The story of cinchona fits well within critique of this history, as researchers including Lucile Brockway, (1979), Banu Subramiam (2024) and Christina Welch (2023) have pointed out that botanical gardens (like Kew) were central to the theft of both plants and Indigenous knowledge. Wild cinchona populations were heavily depleted in the 19th century, while local communities’ expertise was erased.

Unfortunately, there is not extensive documented protest from Indigenous communities at the time, but the erasure of their voices is widely acknowledged in historical research. Today, the ecological and cultural consequences on these communities remain. Some cinchona species are now threatened due to habitat destruction and historical overharvesting, which also impacts the Indigenous communities who continue to rely on these trees for traditional medicine. Today, Kew and other research institutions are increasingly acknowledging that Indigenous ecological knowledge is crucial for understanding conservation and climate resilience. Indigenous people know how to maintain the health of surrounding ecosystems, and there is a striking contrast as protecting the planet now involves dialogues with the communities who have actually practiced this for generations.

On the one hand, this can be seen as collaboration or using science for good. But the more I thought about it, the harder it was to ignore that the environmental crises these projects aim to solve are themselves largely rooted in the empire. The same imperial systems that extracted plants, disrupted ecosystems and displaced Indigenous communities are now the ones framing how we “save” them. I found myself asking: whose knowledge is being centred now, and whose voices are still left on the margins? The power dynamics still remain uneven, and is part of a much wider issue that asks us to think about how we can honour the knowledge of people who have always cared for these ecosystems, rather than simply repeating old patterns under a greener name.

Conclusion: Humanitarian Dreams, Imperial Realities

Kew Gardens has publicly acknowledged its entanglement with empire and colonialism. It recognised that its own history involved the collection of plants, like cinchona, for commercial and imperial purposes. In recent years, Kew has taken steps to address this, including highlighting the contributions of Indigenous communities and re-examining the language used in describing specimens. As this story shows, the focus now needs to be on interpretation and inclusion: giving proper recognition to the original sources and acknowledging the complex histories behind seemingly neutral plants.

In the archives, I found a document that revealed how the British government justified its global cinchona enterprise as an act of public good. In 1864, Clement Markham published A Popular Account of the Naturalisation of Cinchona, describing the transfer of these mass-cultivated specimens to India as “one of the greatest blessings conferred on mankind.” Botanists like Clement Markham framed cinchona’s “naturalisation” in moral terms, arguing that transforming a wild tropical tree into a cultivated British plant symbolised the civilising mission of the empire. In the next blog, I’ll follow the journey of cinchona from Kew’s glasshouses to the plantations of India. This is where the story of Red Bark shifts to the imperial enterprise, as the trees were cultivated on a massive scale to produce quinine for the colonies.

Written & researched by Esme Barrell

Bibliography

Thank you to Kew Gardens for allowing me to use the Miscellaneous Reports Collection, Archives of the Royal Botanical Gardens Kew (London)

– Correspondence 1832-1934

– John Eliot Howard, Illustrations of the New Quinology of Pavon, 1862

Herbarium at Royal Botanical Gardens Kew (London)

– Red Bark Cinchona, collected by Richard Spruce, 1863 [Catalogue No. 52305]

Markham, Clement R., Peruvian Bark: A Popular Account of the Introduction of Cinchona Cultivation into British India (London: John Murray, Albemarle Street, 1880).

Brockway, Lucile H, Science and Colonial Expansion: The Role of the British Royal Botanic Gardens (London/New York: Academic Press, 1979).

Schiebinger, Londa, Plants and Empire: Colonial Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World (Harvard: University Press, 2004).

Stoler, Ann Laura., ‘Imperial Debris: Reflections on Ruins and Ruination’, Cultural Anthropology, 23 (2008), pp. 191–219.

Subramaniam, Banu, Botany of Empire: Plant Worlds and the Scientific Legacies of Colonialism (Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, 2024).

Welch, Christina, Unearthing Indigenous and Enslaved African Horticultural Knowledge in St Vincent Botanical Garden, 1785-1811 (University of Winchester, 2023).

For further information about ongoing research at Kew as discussed in this blog:

https://www.kew.org/science/our-science/projects/history-curation-economic-botany-collections

https://www.kew.org/read-and-watch/medicinal-plant-knowledge-amazonian-ethnic-groups

Sarah Edwards’ recent book on Indigenous plant knowledge, published in partnership with Kew Gardens

Written & researched by Esme Barrell