… reads the plaque on the memorial built to commemorate the capture and death of the Mau Mau leader Dedan Kimathi. Hidden deep in what would have been the dense forests of the Aberdare mountain range, after a thirty-minute drive out of Nyeri and a small trek through the beautiful tea plantations on the hill sides, it is hard to imagine that just sixty years ago, this was a battle ground between the Mau Mau movement and the British colonial forces. The state of emergency between 1952-1959 saw the Mau Mau guerrillas and their supporters fight a violent insurgency against the British colonial rulers and Africans known as loyalists of the colonial administration. The British responded to this violence with widespread incarceration, brutal torture and an ongoing attempt by the British government to suppress information exposing the true nature of their campaign to retain control.

What started as a trip out of Nairobi to visit the brilliant National Museum of Kenya – Nyeri quickly evolved into something even more special. In a quest to learn how the history of the Mau Mau conflict is being taught here in Kenya, the National Museum in Nyeri sounded like a good place to start. The museum is situated inside a previously used “native law court” built in 1924 which mainly dealt with customary law cases before later developing to include criminal cases such as theft and murder. The museum covers a wide breadth of Kenyan history with a particular focus on the 1950s conflict and the Kenyan people’s pursuit for independence, gained in 1963, from the British colonial government. It is a fantastic museum which also houses on its grounds the Matigari Welfare Association Mau Mau Heroes head office, built to support and provide welfare to those who fought in the war. It was here that the day took an exciting turn.

Although Kenya achieved independence from the British colonial government, there has been little concerted, centralised effort towards fair land redistribution. Martin Muteru Nderitu, sub county scout commissioner for the Nyeri centre of the Kenya Scouts Association, has been working to help reclaim land previously owned by and promised to Mau Mau war veterans. Now it just so happened that Martin had a little spare time and was thrilled to take visitors up into the mountain to not only visit Dedan Kimathi’s memorial site, but to also visit a Mau Mau war veteran at his home.

Now it took some searching to finally locate the site of Dedan Kimathi’s shooting and capture. The pursuit that had fixated the British War Office and colonial soldiers for years had finally come to an end on the 21st October 1956. His capture was a pivotal moment in the British campaign to retain colonial control, with the elimination of the forest gangs achieved as 1956 drew to a close. For many Mau Mau veterans, family members, local communities and political figures Kimathi’s memorial site has become an important area to pay their respects to the struggle fought for land and freedom.

However, what was striking when reflecting on the realities of this conflict with Martin was the question, what land and freedom did these fighters truly gain? This was a question that rang in our ears for the rest of the afternoon, forcing us to really comprehend and witness the legacy of this conflict and the reality it has left for those fighting as part of the Mau Mau movement.

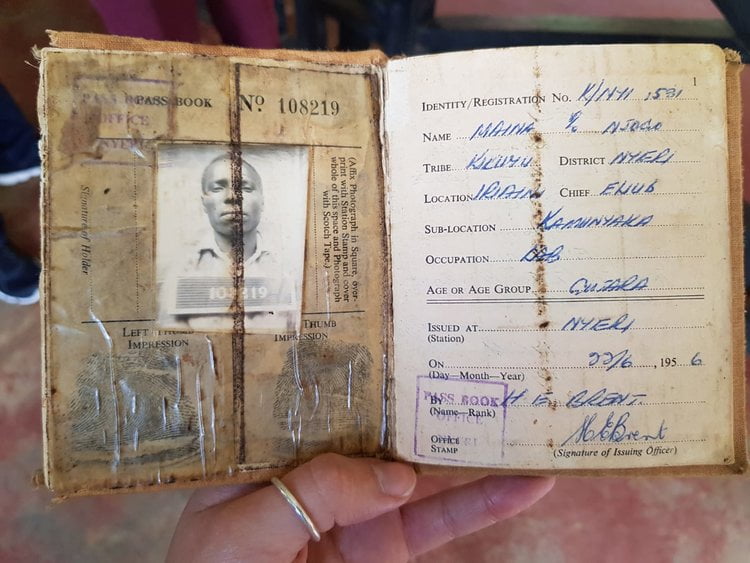

Having dropped by a local shop to buy maize flour, milk, rice and sugar as a gift for our hosts, we made our way to the home of General Haraka – General Reserve, also known as Daniel Mwangi Muchugu. He and his wife so kindly welcomed us into their home with Kikuyu blessings and beautiful songs, some of which Mau Mau fighters had sung in the forest. It was evident that so manyyears on, they found this aspect of their personal history difficult to reflect on. Despite this, they invited us to return one day to spend more time listening to their stories. Having joined the Mau Mau movement to fight for land and freedom, it was another reminder of the outcome of this conflict. You see, Mzee Muchugu now resides with his wife in a modest home situated on his son’s land. And the Kikuyu gentlemen with us – having grown up hearing the stories of the Mau Mau fight – felt more should be done to celebrate the people they see as war heroes. Have these individuals secured land and freedom? Land which they see as rightfully theirs? Or freedom from this legacy the British government spent so long trying to conceal? For these Mau Mau fighters, the struggle continues and the remnants of colonialism still live on, yet to be resolved.

By Beth Rebisz