Shreya Sharma outside a temple in Orissa state. Credit: Shreya Sharma

In the second interview in our “Paper Trails” series, which highlights the work of students and early career researchers telling British colonial histories, MBC volunteer Emily Beswick talks to Shreya Sharma, a restorer and archivist based in Delhi. August 15th marks 73 years since Indian independence and Partition. This traumatic experience is the focus of Shreya’s oral history research. We discuss how the violence of Partition has never been forgotten, as well as Shreya’s other interest, the practice of colonial archaeology in India.

After a History BA at Delhi University, Shreya completed an MA in Archaeology & Heritage management at Delhi Institute of Heritage Research and Management. She is currently a restorer and archivist with the Devi Art Foundation. During the lockdown period, she initiated a project providing experiential heritage learning to children.

Content warning: sexual violence

MBC: Tell me about your research topic. What archives did you use and what did you find?

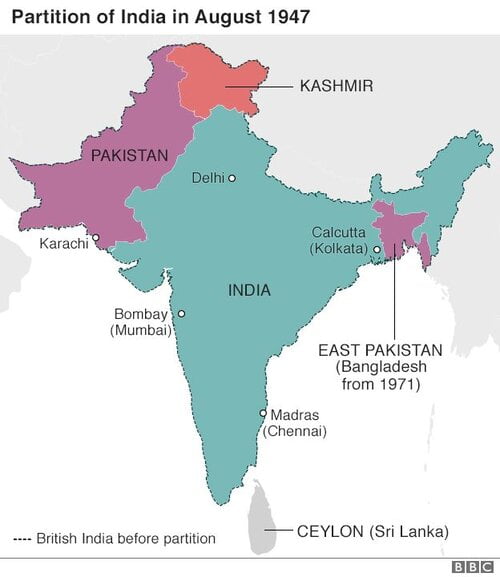

Shreya Sharma: My research is focused on oral history and folklore in Punjab and its neighbouring states in India. The central event is the Partition of 1947, which carved up British India roughly along religious and political lines and uprooted more than ten million people.

I began by conducting interviews with Partition survivors – I cannot think of calling them anything but survivors! They gave me an understanding about a separate but collective shared experience. Although their personal experiences varied, the one thing that was common was the agony and the anger. The interviews helped me understand the emotions hiding behind the historical facts in textbooks.

While interviewing, I started to wonder how the traumatic series of events was interpreted in Britain. I therefore referred to the only archive available that was capable of answering this question – British newspaper reports. I concluded that what was a life-changing and traumatic experience for millions of people in India was reduced to figures in British sources. Moreover, I encountered various articles that praised the British officials for handling the situation well which, in my opinion, was condescending.

“I concluded that what was a life-changing and traumatic experience for millions of people in India was reduced to figures in British sources.”

Were there any personal experiences that informed your research?

Being born and brought up in Chandigarh [the capital of Punjab and Haryana states, in North India], I heard Partition stories even before I could completely understand them. It was part of my childhood in ways that I didn’t even realise. I was probably ten when I had a conversation with a Partition survivor for the first time. It was at this young age that I tried asking around about the Partition and making sense of the aftermath. I ended up reading Khushwant Singh’s novel, Train to Pakistan, after which I understood the gravity of the ‘Partition of 1947’.

Map showing the division of British India into the Dominions of India and Pakistan, 1947. Credit: BBC.

The one question that I always try to ask my interviewees, in different ways, is “Now that you look back, how do you feel?” My motive behind this question is to understand if 73 years of Independence was enough to forget all the violence and loss. The answers are always disheartening.

Even after decades, people still have trauma from the whole experience. They remember it like it happened yesterday. Even if they can’t remember the exact historical facts and names, they never seem to forget the violence.

How would you describe your position as a researcher? Does this present any opportunities or any challenges?

I have an insider position, since from a young age I have been surrounded by families who experienced Partition.

For me, historical facts are important but only to an extent. Partition was not just the splitting of the subcontinent. It had a traumatic and disturbing psychological aftermath. For a holistic picture, I like to collect all the available information from every source. I have an emotional connection with every person I interview. I can empathise and understand their experiences which makes the person being interviewed more comfortable. They usually end up sharing traumatic events that they might have mentally repressed.

The challenge I usually face is to separate my research from my emotions and not be biased by this. It can be emotionally draining.

“Even after decades, people still have trauma from the whole experience. They remember it like it happened yesterday. Even if they can’t remember the exact historical facts and names, they never seem to forget the violence.”

How did the interviews compare with the newspaper reports?

Oral history interviews helped me understand the emotional aspect of the Partition. Instead of seeing Partition as one singular political event, we see it at the level of multiple unique, individual experiences.

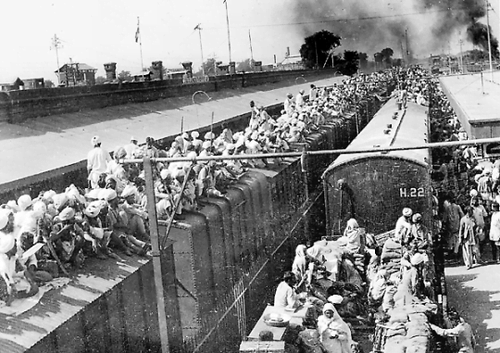

Partition in Punjab. Source: Saktishree DM, Flickr.

Newspaper reports often focused on reporting the ‘numbers’: for example, one million lost their lives in violence. Even if they were trying to report the actual casualties, it was usually a small column in a corner. The initial front page headlines were converted to a few paragraphs in the inner section of the newspaper. While the Indian nation suffered for decades, and tried to overcome and rebuild, British attention to Partition and its consequences faded over time.

Nevertheless, interviews too have their drawbacks. Due to the passage of time, memory fades and people forget dates and other factual information. But what doesn’t fade is the trauma and the pain.

Did you find that an interviewee’s gender shaped their memory of events?

Partition was experienced differently by different genders. Women were targeted because their position in society was shaped by the concept of ‘honour’. There was a lot of inter-communal violence, one religion or one community against another community, and women suffered more from violence, rape and kidnapping. In fact, parents started getting religion-specific tattoos on their daughter’s hands to reduce the risk of kidnapping and forcible conversion from the opposite community or from getting raped.

And what do men tend to remember?

The people I talked to had very different experiences. Some of them were involved in the violence themselves, at the start, and when they saw how things are, they got a sense it was not right. I also met people who committed violence on the other party, and they regret it.

There’s another set of people who have experienced it through their family, mothers, sisters. They tell how they used to hide their female relatives in cloth when travelling, trying to safeguard them in whatever way possible. One story I would like to share was that of a man who was trying to migrate with his wife from somewhere in Pakistan to Lucknow in India. They encountered raiders, who raped his wife right in front of him and made him watch. The wife died eventually from all the pain and trauma. It was horrible to hear and so sad.

“Oral history interviews helped me understand the emotional aspect of the Partition. Instead of seeing Partition as one singular political event, we see it at the level of multiple unique, individual experiences.”

To shift topics a bit, you currently work as a restorer at the Devi Art Foundation and have researched the history of archaeology in India for another project. What were your conclusions?

My other research interest is the history of archaeology in India and how British colonialism may have been a setback to the field.

The way that archaeologists decipher the meaning of a structure or object is shaped by their own contexts and frames of reference. The approach of British archaeologists in India lacked the necessary local knowledge and understanding, so I feel many objects or data were misinterpreted.

My research focused on numerous excavation reports. I started with the survey by Alexander Cunningham, a former army engineer who later became an archaeologist. I could see a cultural difference in how he perceived various objects and details in monuments. Since he was not from India, he did not really see certain things the way I would, or other Indians would. For example, looking at a Vishnu idol, I would be able to say this is Lord Vishnu – but for him, it was just “some lord, some god”, and that is how he interpreted it. The issue is that he took a lot of artefacts back to Britain, so it is hard to counter his interpretation.

“The way that archaeologists decipher the meaning of a structure or object is shaped by their own contexts and frames of reference. The approach of British archaeologists in India lacked the necessary local knowledge and understanding, so I feel many objects or data were misinterpreted.”

And how does using oral history enrich archaeological practice and learning?

How you use oral history depends on the period you are looking at. If you are studying the recent past, usually the last three to four generations, oral history can help archaeologists and researchers to unearth a site that might be of important historical significance. Oral history and interviews can provide narratives, social meaning and contexts for the object. If the site dates to an earlier period, the reliability of the oral history is not enough. It should be used with other sources as well to corroborate the information.

One of Shreya’s most prized possessions – a coin issued by British Government in 1945 which she inherited from her grandmother. Credit: Shreya Sharma.

I would say oral history also includes mythology. Various mythological works like the Ramayana and the Mahabharata have been used by archaeologists to excavate particular sites. The whole mythological story might not be true, but certain aspects and certain things in the story might be. Oral history in this context doesn’t have to be taken as the sole truth but one gets context and possible answers to several questions.

Using oral history and mythology has the potential to decolonise archaeological practice. I feel like oral tradition and mythology are overlooked in western archaeological research – the focus tends to be on material finds. But using oral history can give a more holistic picture, if studied alongside other sources. For oral history to come to the forefront, it is necessary to overcome various social biases. It is necessary to record and give importance to oral history from every group of people, overcoming exclusions based on social status, race or gender.

It is also important to challenge the supremacy of English over various Indian languages. Few students opt for a higher education in these indigenous languages if given a chance. This idea of English language supremacy is definitely a by-product of colonialism.

How does your work resonate with current discussions about colonial history in India?

We can still feel the aftermath of the British policy of ‘Divide and Rule’ in various forms till date. The inter-communal riots we see today in our country show how it created a divide between the two communities so deep that 73 years of independence could not help us unite completely.

It is necessary to read and talk about the violence the country faced and to understand its reasons and repercussions. All the Partition survivors have one piece of common advice for the new generation – “learn from the past”.