Dr. Amara Thornton, credit: Matthew Knight

Our latest project “Paper Trails” platforms the exciting new directions of research into British colonialism, especially outside Britain. We are interviewing students and early career researchers for their perspectives on using colonial archives and challenging established narratives about colonialism.

In the first of this series, Dr Amara Thornton, a historian specialising in the history of archaeology, spoke with MBC volunteer Emily Beswick about her research, process, and experience with archaeological archives.

Dr Thornton’s PhD focused on British archaeologists working in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East between 1870 and 1939. She is currently Research Officer at the Ure Museum of Greek Archaeology.

MBC: Could you tell me about your research subject and what archives you are using?

Dr Thornton: My research subject is the social history of archaeology. I’m less interested in what people found or what theories they constructed about the Ancient World than how they engaged with archaeology. I look at British archaeologists working abroad in the late 19th and early 20th century, connecting their experiences to wider social, political and economic trends.

I explore a number of different archives. To get a sense of the political and economic context, I use governmental records, for example colonial office files in the National Archives. I’m also interested in the societies that sent and supported archaeologists in various locations – those societies were mostly based in London. Finally, I look at local groups, although evidence for these groups is often harder to find. It’s across a number of different sets of records really.

I want to bring out the humanity of the archives and try to populate the history of archaeology with individual experience. The more experiences, the more voices, the better.

“I want to bring out the humanity of the archives and try to populate the history of archaeology with individual experience. The more experiences, the more voices, the better.”

How did you come to the topic – did any particular experiences inform your questions?

During my MA in Museum Studies, I came across a collection that belonged to two archaeologists who worked in Jordan in the 1930s. The collection was mostly photographs, annotated on the back. I discovered that they belonged to a husband and wife team who excavated at Petra and that the wife’s diaries were still in Cambridge. I didn’t know anything about the history of the British occupation in Jordan, I didn’t know anything about the context – but I was interested in their history and why they were there, and what they were doing. I ended up basing my PhD around these two and added three more archaeologists who knew them. This allowed me to explore the social networks within British archaeology in the colonial Middle East.

What did the annotations say? What drew your attention?

The annotations didn’t say anything particularly enlightening! They just contained personal names, but I’ve always been drawn to biography and personal histories. There was a personal element to the photographs, which showed their house in Jerash (an archaeological site) and people they knew. I didn’t know these people at all, but I found the pictures compelling.

Many historians have written histories of Empire from a biographical perspective. What do you think is particularly useful and interesting about that approach?

Everyone has a different experience of empire, and all of those experiences add up to a mosaic of lives formed by a particular circumstance, time, and set of relationships. It’s very difficult I think to have a monolithic view of what Empire is, because Empire is different in every single place.

At the same time, you will often find people moving between contexts – for example, someone who’s been an official in Egypt, Palestine, Cyprus and maybe the Caribbean. Therefore, there’s a certain connectedness within the Empire, but it is also really important to remember the local context. It’s that complexity that I find interesting. Also, I suppose because I’ve moved countries – I grew up in the US but live here – I’m quite interested in people who move their location and what that means for them as ‘expats’. They had to shift their identity in a way.

“It’s very difficult I think to have a monolithic view of what Empire is, because Empire is different in every single place.”

You mentioned earlier local groups, and how hard it is to find records about them. But could you say more about what you can use?

It depends on which local groups you are talking about!

For example, there are British people who lived in a colonial context and the records of those groups will often be in the UK, in the collections of local archaeology societies and universities.

And there are people born in and embedded within a colonial context as colonised people. For example, Egyptians who worked on archaeological digs are reflected in records in Egypt, but they do not show up as prominently in British records. I just worked on an exhibition at the Ure Museum about John Garstang, a British archaeologist working in Egypt in the early 20th century. He had an Egyptian foreman, Saleh Abd El Nebi, who he was quite close to; they’re mentioned in his publications and some newspapers. In the archaeologist’s archive at the Garstang Museum in Liverpool, I found a field report written to Garstang’s funders which was signed and sealed by the foreman. Garstang wrote something like ‘this is the signature and seal of the foreman who has been my friend and servant for five years. He’s been doing xyz.’ That was really nice to find. The Museum also has letters from British assistants which mention Abd El Nebi. You can get a sense of what he’s doing from these records, but it’s not in his voice.

There are projects ongoing in Egypt to recover the lives of local inspectors, who were Egyptian, and who often don’t show up in European records. There are efforts to digitise and translate their records, which will blow open a whole other perspective on how archaeology was done in Egypt. It will be a much richer resource for understanding how archaeology worked there.

“Egyptians who worked on archaeological digs are reflected in records in Egypt, but they do not show up as prominently in British records.”

Even though the records you found in Liverpool were not reflective of this foreman’s voice, do you think that there is a way that you can tell his story with that archive?

Definitely! But it’s just not… It’s a sentence here or there that you have to dig to find. However, if you understand the ways that archaeologists tend to operate, you can start to work out where to look. The Garstang Museum has letters sent back to the Institute where sometimes you get little ‘nuggets of news’. Or you can use field records, which have summaries of what was happening and tend to name who’s doing what. There might also be notebooks written by an archaeologist which are more site-specific. But you have to look across a number of different records to piece together the story.

Has your research stimulated any thoughts on archaeology as a discipline today? Do you think archaeologists look at their own history?

When I started my research in 2006, most of the people in the archaeology department didn’t understand why I thought it was important. They assumed I was just interested in gossip – and in a sense, I am interested in gossip, because gossip is part of the social history of archaeology! However, this has changed a lot over the past two years with the decolonisation of museum collections becoming a big talking point. People are starting to think more directly about the context of archaeological collections in the UK, and whether they should be given back to their countries of origin. That’s encouraging and I hope it continues!

These discussions are important because they have implications for how we view museums, their collections and what kind of stories are being told, and who is given credit for discovery. The history of archaeology has always been an important storytelling device but now I think people don’t necessarily want the same narrative of ‘white man goes to foreign place and finds things’, because it’s much more interesting and more complicated than that!

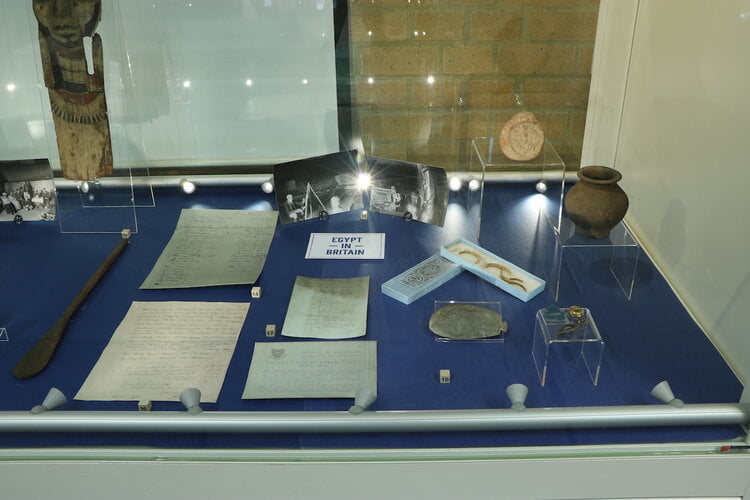

In my opinion, museums should be putting archives in the case with the objects to say ‘this is the reason why we know anything about this thing’. In the Ure Museum exhibition, we put archives in the cases because I thought it was important to show the people who are responsible for digging the stuff up. The information coming out of those excavations should be given as much value as the found object. Hopefully more museums will start doing that, and if they’re not they should be.

“The history of archaeology has always been an important storytelling device but now I think people don’t necessarily want the same narrative of ‘white man goes to foreign place and finds things’, because it’s much more interesting and more complicated than that!”

Egypt in Britain exhibition, Ure Museum. Courtesy of A. Thornton, 2020.

And that would help contextualising museum collections, demonstrating clearly where they’ve come from, histories tied to colonialism and possibly theft…

Yeah, but it’s also about individual histories too – any object is going to be found by a person with their own history and their own reason for being in that place at that time. I want to get as many people as possible to understand the individual stories, and not to think about activities that happened in an imperial context as being a monolithic story, like we’ve been talking about. All of these things are built on individual decisions by individual people.

I hope that more people will start asking, when looking at an object in a museum, ‘I wonder who actually discovered this?’ I want them to ask questions about what that moment of discovery was like, and also think about the local context. All of the excavation sites had villages alongside and often the villagers are the ones digging on the sites. Their histories are part of the whole context of the site. Often those details are erased, especially if the archaeological site becomes a tourist attraction. But reintegrating their stories gives a totally different picture of what the site was like in comparison to an image of clean, beautiful columns!

One last question – you talked about getting as many people as possible to be researching the history of archaeology. You’re involved in digitisation projects, are they an important part of this? How essential is it to expand accessibility to archival material?

Often archival material is held by an institution, but they may not necessarily have the resources or time to make those records available for any kind of research. People don’t know what is around – so they don’t ask to see it – and therefore there’s no institutional push for making archives accessible, because the perception is that there’s no demand.

You have to start somewhere. I’ve tried to – where it’s possible – find funding to make archives accessible. I did a project funded by the Council for Research in the Levant to digitise the diary of the two archaeologists I researched for my PhD, the ones excavating at Petra. But it was important not to just whack stuff up online with minimal explanation or contextualisation, which is what tends to happen with digitisation projects. The problem is, then, there’s not enough information to make that stuff meaningful for anyone but a small minority of people who know what they’re looking for.

What is needed is continued and sustained investment in digitising and cataloguing and meta-data creation, but also in public engagement. It’s important to give enough contextual information so that people can understand what they are reading but also explore the material in a way that makes sense to them. Not just ‘look at this nice archaeological archive’, but a deeper understanding that, for example, Petra is part of a country that was occupied by Britain at a certain period of time. It’s also a tourist attraction – there’s lots of different ways you can look at it. I’ve tried to do that by not making it just about archaeology, but hopefully about things that other people might be interested in too.

You can read more about Amara’s work here, discover her personal research blog, or follow her on Twitter at @amalexathorn.