In this guest blog post, Pippa Le Grand, a recent MA Historical Research graduate, reveals the obscured colonial histories behind many objects at Weston Park Museum, Sheffield.

In discussions about the legacies of colonialism, and the nature and purposes of museums, it is important not to forget Britain’s many municipal museums. Almost everyone who grew up in the UK has experienced such places, from badly-lit repositories of memorabilia to lively hubs of activity with nationally-significant collections. Perhaps thanks to the London-centric nature of our culture, their history is ill-understood and ill-contextualised.

I spent most of 2020 researching one such museum – Weston Park Museum in Sheffield, where I’m also lucky enough to work – and the city’s history of collecting and displaying objects. I tried to set this museum’s development in context of these other activities, understanding the municipal museum as an important point of connection within a network of collecting and displaying objects and knowledge. Through objects, events and people, the story of Sheffield’s development as a major centre of imperial collecting became clear. Each of these people, events, and objects was and is significant. In this post I explore just three, to highlight how this network operated, and how empire existed in the fabric of museological culture in Sheffield.

The Reverend and Mrs Bayne’s collections

Mappin Art Gallery, opened in 1887, now part of Weston Park Museum. Image credit: Museums Sheffield

In 1870 Sheffield’s Literary and Philosophical Society hosted a ‘conversazione’ – a meeting for members and guests, like local industrialists, to display their personal collections, and to see art and crafts available from South Kensington [1]. Also present were men from similar societies from Leeds, Rotherham and “various parts of the country” [2]. Sent by the Reverend Bayne was

“an Abyssinian relic, consisting of an ancient sacramental bread plate from Magdala”

and from Mrs Bayne came

“an East Indian fan, blotting book, and lady’s workbook, presents from the Rajah of Scinde [Sindh], an Egyptian bracelet, and a Persian vase, used for sprinkling water over guests (brought home after the Persian war).” [3]

This is a fascinating insight into the private collecting habits of Sheffield’s well-off. The Reverend’s relic from Magdala – in Galilee, Israel – came via Ethiopia, but how? It’s likely that it was bought or ‘found’ on a trip to Ethiopia, or whilst he and Mrs Bayne were in, or en route to, India. Some of Mrs Bayne’s artefacts were collected and “brought home after the Persian war”. The pair were able to travel through parts of Iran and Afghanistan controlled by the British after this war, and to reach the relative safe haven of India where they visited, and perhaps were even hosted by, the Rajah. [4]

“ In Sheffield, empire came home to contribute to British conceptions of self and other.”

This journey was shown off to friends and peers at home through objects they collected, and presented to the Society as evidence of the ‘knowledge’ of Asia they now possessed. They shared this new knowledge with people who also identified themselves as intellectual through their display of significant objects. The ‘Abyssinian relic’ and the Indian objects reinforced perceptions of the East as familiar yet exotic, wild yet somewhat tamed by the British presence. In Sheffield, empire came home to contribute to British conceptions of self and other.

William Bragge, Master Cutler and enthusiastic collector

William Bragge was a classic Victorian entrepreneur and self-taught intellectual. The breadth of his society memberships, alongside his engineering work, roles as Master Cutler and manager of a Sheffield metalwork firm, and interest in collecting objects throughout the empire, make him a great example of how Victorian elite society often centred on objects and displays. Bragge existed at the intersection of industry and collecting, and often appeared at meetings of the Literary and Philosophical Society, town council and Company of Cutlers, advocating for the establishment of a cutlery museum for Sheffield.

An Egyptian scarab, dating from 1550-1069 BC. It was one of 160 objects collected in Egypt by William Bragge that are now in the Museums Sheffield collection. Bragge was part of a ‘long tradition of imperial theft’. Image credit: Museums Sheffield

In 1870, the inventor Henry Cole [5] visited Sheffield and engaged in a heated discussion with Bragge, negotiating support for Bragge’s proposed museum from South Kensington. [6] It was finally concluded that Sheffield should apply to South Kensington for funds and significant objects. In 1874, a year before Weston Park Museum opened, Bragge addressed a meeting at the Sheffield School of Art.

“If they could get in Sheffield,” said Bragge “…a metal work museum, where the cutler shall see the most original – the earliest cutlery that the world can show – where he shall see specimens of the whole of the historic period, the medieval period, and come down to the present time; where he shall see every article dissected and laid before him, so far as they could be, did they not think that that would cause the cutler to enter a much higher opinion of his art than he did before?” [7]

“Local debates over Sheffield’s proposed cutlery museum intersected sharply with imperialist fears about the state of Britain’s industries”

Cole’s support was clearly insufficient to make this happen – local support would also be essential. Bragge’s determination was grounded in the belief that Sheffield needed to compete with other centres of steel production: industrial competition was driven in the later nineteenth century by a seemingly endless series of international exhibitions throughout Europe, North America, the settler colonies and India. Local debates over Sheffield’s proposed cutlery museum intersected sharply with imperialist fears about the state of Britain’s industries, in comparison to other European countries, and those of Britain’s own colonies.

Bragge was a pivotal figure – he was a point of connection with South Kensington, with metalwork industrialists, with local societies, and with the new museum in his home city, Birmingham, with whom he organised a loan exhibition of Indian cutlery in conjunction with Sheffield City Museum. By showcasing the best work he could find from the East, Bragge sought to demonstrate what Sheffield’s artisans could, and should, in his view, have been doing to maintain industrial superiority.

Bragge’s impact on Sheffield’s museological culture is palpable today, as the collector of more than one hundred objects in Museums Sheffield’s Ancient Egyptian collections. His story combines both a long tradition of imperial theft – travelling to Egypt and simply removing objects – with an interest in imperial industrial competition. Ultimately, Bragge’s collecting activities demonstrate how industrialisation in Britain was intimately bound to imperialist actions in its colonies.

Weston Park Museum and the Mappin Gallery

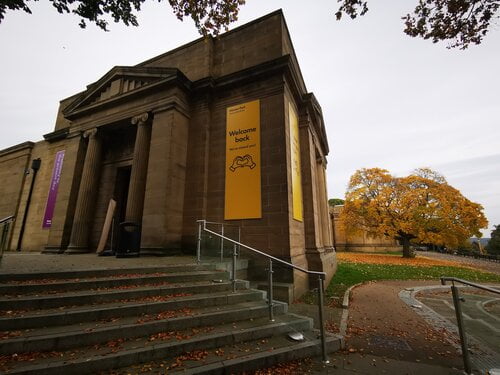

Weston Park Museum today. Image credit: Pippa Le Grand

Today, there is a relative wealth of information available about the establishment of Weston Park Museum, including important forthcoming research from Curator of Natural History, Alistair McLean. Yet Sheffield’s narrative of itself tends not to identify the museum, now a resolutely family-friendly, welcoming space, as a repository of colonial goods, as well as colonial rhetoric, both visual and linguistic. Neither was its 1875 opening expressed in these terms, instead reported as part of the development of Sheffield’s public space. The desire to provide more leisure activities for working people is part of the familiar story of Victorian England, with philanthropic and moralistic aims of relieving workers’ poverty, for largely industrialist purposes.

However, the museum, known then as Sheffield City Museum or simply the Sheffield Museum, saw the convergence of the collecting and display habits established in the city, including those of Bragge and the members of the Literary and Philosophical Society. How could it be anything other than a colonial enterprise, when it housed the collections of men like Bragge, and archaeologist Thomas Bateman, whose objects gathered in Egypt and Persia also became part of the collection in the 1890s? [8]

“Yet Sheffield’s narrative of itself tends not to identify the museum, now a resolutely family-friendly, welcoming space, as a repository of colonial goods and colonial rhetoric.”

Sheffield may not possess the same overt histories of human trafficking and ownership in comparison to cities such as Manchester and Liverpool, but its municipal museum and associated museological culture deserves attention through an imperial lens. Only then can we better understand how local museums contributed, and can continue contributing to, an imperialistic British identity.

The museological network, of which Sheffield was part, stretched from highly local activity to major national museums, particularly South Kensington, and to a global imperial system of exploitation and dominance. To understand Britain’s uncomfortable, often disdainful relationship with its empire, then we must look first at our own communities and the museums at the heart of them.

Pippa recently graduated with an MA in Historical Research from the University of Sheffield, where she examined the relationships between British imperial and global history. She works in digital marketing and as producer for her company Only Lucky Dogs Theatre, in collaboration with the team at Portland Works, Sheffield. Pippa can be found on Twitter @pippalegrand.

Footnotes

[1] Referring to the Department of Science and Art’s museum and School of Art in South Kensington, which would become the V&A.

[2] The Literary and Philosophical Society’s Conversazione.” Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 4 Feb. 1870, p. 3.

[3] Ibid.

[4] The title Rajah was a term given to minor dignitaries and nobles in India during the British Raj.

[5] Organiser of the Great Exhibition, with considerable imperial connections attached to this role, as well as variously the Chairman of the Council of the Society of Arts, secretary of the Department of Science and Art, and the first director of the Victoria and Albert Museum. More from the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography and Anthony Burton’s Vision and Accident (V&A, 1999).

[6]” Yorkshire College Of Science.” Sheffield Independent, 25 Jan. 1870, p. 7. ” A Cutlery And Metal Museum For Sheffield.” Sheffield Independent, 3 Sept. 1870, p. 6.

[7] “The School of Art.” Sheffield Independent, 21 Feb. 1874, p. 3.

[8] Thomas Bateman’s involvement in Sheffield’s museums can be explored here and through the life of his son, Thomas, here.