“It’s 400 years

and it’s the same kind of living

Brutality, hypocrisy, same immorality

We can’t take no more of that…

Say, say, say, say

Lion! Lion!

We say Lion! Lion!

We say Lion! Lion!

Because we know

you can’t fool the youth no more…”

It has been 40 years since Babylon was released, and yet for many reasons (including receiving an X rating in London and being banned in the US until 2019 for being too controversial…), it did not reach the audience that it deserved to. Babylon is shot on the streets of Brixton and Deptford, the year following Thatcher’s rise to power, and the year before the 1981 Brixton riots which were triggered by police tensions and unemployment. At our latest event we joked that Babylon is a key counterpart to season 4 of The Crown, because it shows a side of Britain that couldn’t look more different, but was happening at exactly the same time.

On 28 November 2020 we held our first A History of Everyone Else film screening and post-film discussion about Babylon. We wanted to bring together both avid fans of the film and people who had never ever heard of it. We had around 30 people join us virtually during lockdown, including one of the actors Brian Bovell. It was an intimate event, with guests sharing stories about their personal relationships to the film, so you won’t be able to watch a recording on our YouTube channel. But the post-film conversation was so inspiring that we’ve decided to write this short post about it (with a few quotes from some of our guests).

We had not heard of the film Babylon before this year. In fact, it is difficult for us to count many black british films we have seen, ever. But over the summer, whilst living with her parents during lockdown, Rhianna’s parents introduced her to Babylon and she was immediately hooked, and confused as to why she hadn’t seen the film before.

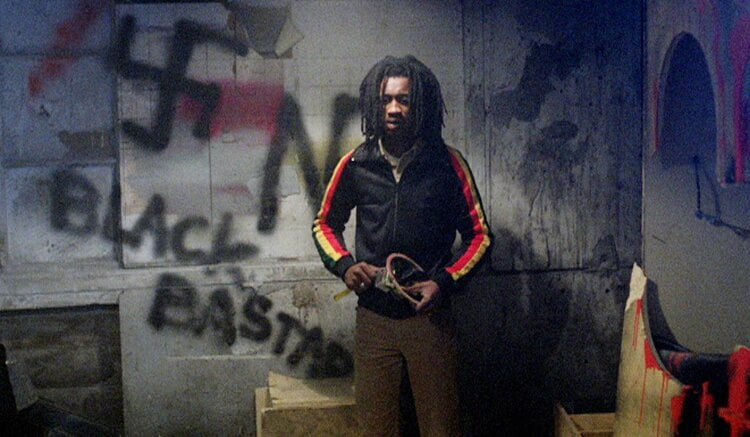

Babylon follows the life of Blue, a young DJ and mechanic, over the course of a week that goes from bad to worse. The movie shows the impact of sus laws on young black people in London (44% of those arrested under “sus” in London were Black people, even though they made up only 6% of the city’s population) and the comfortable position of the National Front in British society (with logos prominently painted across many buildings). But despite the violence and the pain that is shown, many of our guests have watched Babylon over and over again, and will continue to do so, because of the reggae soundtrack of the movie: “From the outset the music and action was full of youthful spirit.”

In fact reggae both fills the soundtrack and drives the narrative plot, drawing attention to the socio-political relevance of the music-based culture of soundsystems in London. Soundsystems would use unique records, often sourced from Jamaica, to create a performance that most resonated with the audience (tested by crowd feedback). Traditionally they were set up outdoors but in cold inner-city London, battles took place in clubs, recreational centers and school halls. The music itself, with its Jamaican origins and lyrics about black political empowerment, presents a way in which to identify away from the national ‘home’ of Britain. Over the course of the film, Britain is revealed to be increasingly hostile towards black people – its citizens that were invited to live here but had also always been a part of the British empire. Music provides a safe space for these characters, while for us, we hear the ongoing reverberations of the British histories of slavery and colonialism every time we see scenes of London set against Babylon’s reggae soundtrack.

One of the things that struck us and our guests was the ‘glimpse’ into an unexplored moment of recent history. Unlike the many ‘historical’ films and TV-shows focused on race and immigration (Small Axe, Selma, 12 Years a Slave, Hidden Figures…), this film is not a reenactment of the past. This is the world in which the actors actually lived. The films listed always tend to have a particular gloss to their storytelling, that somehow makes palatable to modern audiences the realities of past racism. Yet watching Babylon feels almost like watching a documentary. Nothing is manufactured – the clothes, the music, even the ‘extras’ are all completely of their time.

The language too. Many of us were shocked by the severity of the racist language used against Blue and his friends. These men are verbally abused on the street, always and everywhere, prompting people to remember hearing similar racial abuse around them: “I grew up and went to Uni in Scotland, where there were few Black or Asian people at our school, and more sectarian division than racial (in my world, anyway). But I remember all those words being used (casually, descriptively, not deliberately racist) by grown-ups around if we saw something inter-racial on TV. And enjoying The Black and White Minstrels! It seems like a different world, thankfully.” Even the refuge of the kids in the film – the garage where they dance to reggae together to prepare for their soundsystem battle – is not a safe haven for long.

This point led to a discussion on the different attitudes between 1st and 2nd generation black immigrants in Britain might have towards the police. The Windrush generation arrived in Britain between 1948 and 1971 from Jamaica to meet job shortages after World War Two, but black servicemen and workers found themselves without jobs after a “colour bar” was introduced in many industries. White workers, often backed by unions, refused to work alongside black people. At our event, older black guests on the call spoke about their struggle to sometimes relate to younger generations of anti-racism campaigners. “In our day… you just couldn’t fight everything. You had to pick your battles, and ignore a lot of the language that came your way.” “Even going out clubbing felt like a political act… there would be dozens of police on horses stationed outside nightclubs in Brixton.” How do you handle the police if you are growing up black in Brixton in the 80s? Do you try to ignore them, to lay low and stay out of trouble? Or do you choose to fight against how you, your friends, your family, are being treated? And what does this do to your relationships with other people – in particular, if you are a man, your relationships with women? Where does all of that anger eventually spill out? One issue we spoke about was the level of gendered violence in the film, how both race and gender shape the lives and choices (or lack thereof) of the main characters, and our desire for more stories to be told that centre the lives of black women.

Actor Brian Bovell (who plays ‘The Scientist’ in the film) gave us an incredible insight into the making of the film – from the scenes that were improvised by actors in the audition room and then included in the script, to the fact that all of the actors were shocked when the film received an X rating in the UK and was banned in the US. Beforehand, optimism surrounded the film’s release. “We really felt like this would be the beginning of our stories getting told.” Sadly this optimism was crushed when everybody involved realised this wasn’t going to be the case. Soon everyone realised the gatekeepers would make it even harder for black stories to be told moving forwards, making us connect Babylon to recent controversies around Blue Story – a film by young black creatives that was banned by two UK cinema chains in 2019 for undeniably racist reasons. Not only this, but almost 40 years later, stop and search is a graduation of the “sus” laws, disproportionately used against black people in Britain.

Babylon made us all think slightly differently. For one guest, “it felt like a coming-of-age film, especially when you see Blue pack up and leave his home, carrying around all of his belongings in a small bag from place to place for the rest of the film.” There is a particularly hilarious scene during an engagement ceremony, in which it is clear that the main characters are just young boys, still at the stage where they are not so interested in romance as much as their intense relationships with their friends through soundsystem culture. For our guests on the call who had grown up in Nigeria, the character that stood out was Beefy – one of Blue’s best friends. People spoke of seeing themselves, or their friends, in this character: his anger, pride, humour, and pain wrapped up in one.

And finally, for a lot of us, including Bovell, the film was so moving and so enjoyable because of the central role of joy, which left us wondering whether a similar film made today would be so fun and joyful. It was Meera’s first time watching it, and she shared about how much she laughed and smiled and wanted to dance while watching – far more than she expected to! What comes across is the political act of joy, which made us think about the Stonewall riots and other examples of state violence where love and joy are such a threat to existing power relations in a society that they are brutally repressed.

Our platform A History of Everyone Else is all about unlearning through learning. We believe that the stories of the forgotten, the marginalised, the silenced, they give us all a chance to question sweeping narratives of progress and modernity that do not do justice to everyday people’s realities – like the people represented in the 1980 cult classic film, Babylon.

If you watch it based on our recommendation, we’d love to know what you thought of the film. Feel free to email us on rhiannailube@gmail.com or mnsomji@gmail.com to get in touch – or tell us which film you think we should show next!