For the latest instalment of our Paper Trails series, MBC’s Andrea Potts spoke with artist Mataio Austin Dean about their artistic practice, the relationship between art, historical research, and imagination, and the limits of the colonial archive.

Mataio Austin Dean uses intaglio printmaking to create images and symbols that explore England’s and Guyana’s darkly intertwined histories, throwing light upon moments of resistance as well as unearthing stories of coloniality and rebellion embedded in English landscape and architecture. Austin Dean’s practice is research-driven, exploring Marxism as a framework for emancipatory praxis. English and Guyanese oral cultures are at the heart of the work. Reimagining, writing and performing folksong and poetry breathes life into the printed landscape, making the past tangible while presenting liberating modes with which to confront the present.

MBC: How would you describe your artistic practice?

Mataio Austin Dean: I’ve got quite a broad practice, which takes in printmaking, performance, writing and drawing. Research practices are built into this. I’m interested in the boundaries between making and research. A lot of my work has been concerned with ideas around decoloniality, and specifically, the intertwined histories of England and Guyana. I’m half English, half Guyanese. Or rather, my mum is from Guyana, and I grew up in Portsmouth. I’m interested in how these histories are connected, and how they’re perceived. It’s not just about historical methodology, it’s also about historiography and how histories are remembered through time and space, what’s forgotten and what’s not.

What is your process? Does your historical research prompt an idea for a piece of art? Or is it more complex than that?

It depends. Sometimes you just have a feeling about something, it can be quite intuitive. Sometimes I’m doing all this research and a particular subject matter and imagery comes out of that. Sometimes I’m like, right, I’m going to find this out and I’m going to try and search for this. It’s a real mixture of research and intuition.

“So much of this information is prohibited. So much of this stuff is just hidden away.”

You use a lot of different historical sources. How do you understand these archives? Are they fruitful resources? Do you find that there are limits to the archives and can art overcome those limits?

I think that they can be very fruitful, but also there’s normally large gaps in them. This is also about access. I have limited access. I’m a visiting research fellow at the Institute of Advanced Studies, UCL. I have some access to certain things but so much of this information is prohibited. So much of this stuff is just hidden away. I’m looking into Unilever at the moment and I’m using its own archives. So, there’s issues with power.

But I also like to think that through artistic and aesthetic engagement with this material, there can be processes of imagination and visualisation. This can help make things more real and tangible in terms of people today understanding what was going on in the past, but also trying to build into that a kind of liberatory mode or some kind of way in which we can think about or talk about what a decolonial future looks like. A lot of my work has drawn on Marxism as a kind of liberatory praxis. And I think art provides great spaces to imagine these things with the goal of their realisation or actualisation.

Yes, you include representations of anti-colonial resistance in Guyana in your work, and you’ve previously described this as an act of solidarity.

Yes, I’m quite interested in solidarity through time and space. It’s quite difficult to know a lot about these histories. But I’ve always engaged with this through the lens of oral culture and folklore. There’s a certain amount of archival material to work with in the UK but to look at family history in the Caribbean, you hit a brick wall quickly because of the lack of documentation of enslaved people. I think about my own family history. On my dad’s side in England, even though everyone was just ordinary working class people and peasantry very far back, you know, there are still records. Whereas in Guyana, the records stop with slavery. So I think there’s a certain kind of imagination involved and oral history becomes increasingly vital.

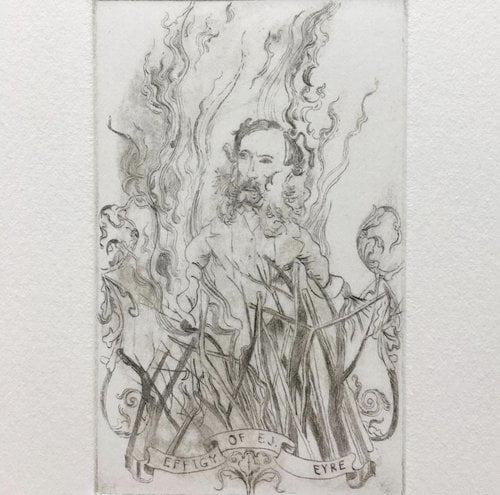

I also try to imagine forms of solidarity between workers in England in the imperial metropole and workers in colonised lands. I read about where an effigy was burned of Governor Eyre, who was the colonial governor who put down the Morant Bay rebellion in Jamaica. Supposedly, an effigy of him was burned in London by workers on Clerkenwell Green. I took this as a kind of symbol of solidarity with anti-colonial struggle. In fact, you know, it’s a lot more complicated than this and the extent to which the effigy burners were really demonstrating a true kind of anti-racist solidarity is hard to say, because there are other reasons why Eyre was unpopular in the UK. And there are all sorts of issues of white liberalism that come into this, but I think it’s important to try and forge solidarity, even when it’s difficult.

Effigy of E.J. Eyre

‘I think it’s important to try and forge solidarity, even when it’s difficult.’

Some of your work attends to the presence of colonialism in Britain itself. It highlights that colonialism is not something that only happens away from Britain, it’s embedded in finance, in culture, etc. in different ways. How do you show this in your work?

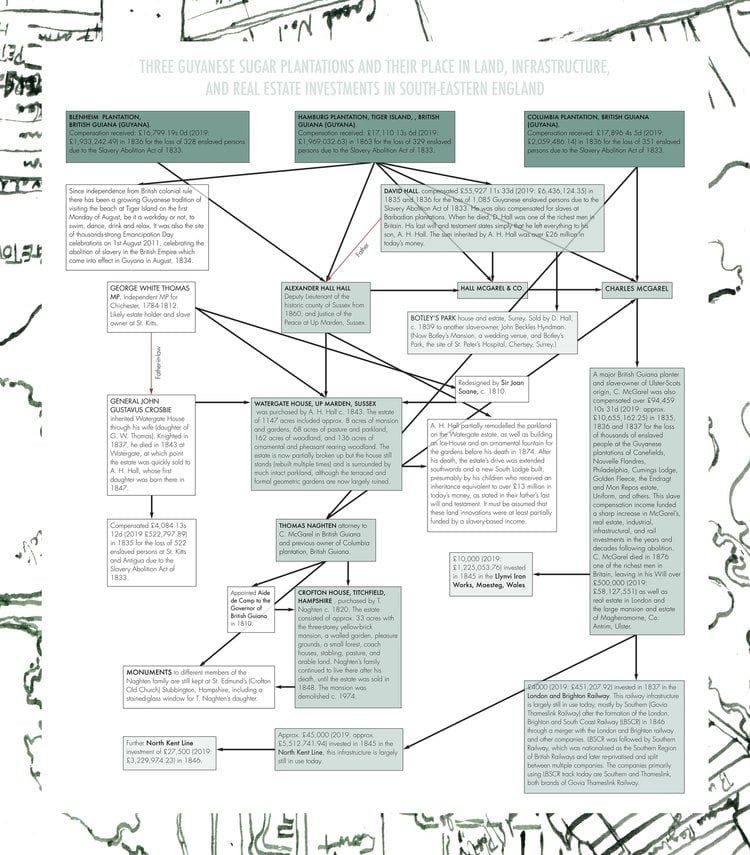

Recently I did some works that are diagrams. I gathered information, including from the Legacies of British Slave Ownership database at University College London (UCL), to look at the ways in which finance, land ownership and real estate – real concrete forms of material and economic culture – have inputs from colonial exploitation and transatlantic slavery. I was specifically looking at southern England, just because I wanted to focus on an area that I knew, and Guyana. I was looking at how specific plantations in Guyana fed into the wealth of certain English individuals and companies, and how that wealth was funneled into land ownership or railway infrastructure or finance capital.

In some of your work you mix imagery relating to British colonialism in Guyana with that of the English countryside. What is the significance of this pairing for you?

Within England, I think that the countryside is still the last refuge of Englishness as whiteness. At least, traditionally, the mainstream, hegemonic, racist way of seeing the racial makeup of the country has seen blackness as an urban phenomenon and the countryside as a place of whiteness. And it is true that when we’d go as a family to the countryside, the people of colour in my family, especially people with darker skin, would not always have a great experience for many people of colour in the countryside. Obviously, not every time, but often something would happen and that’s a very real experience. And it’s something that artists have dealt with before, including Ingrid Pollard who’s also of Guyanese descent.

“I was interested in the way in which Guyanese labour has directly fed into making the English countryside what it is.”

I was interested in the way in which Guyanese labour has directly fed into making the English countryside what it is. When I was doing these diagrammatic works, I was looking at land investments which had come from money from Guyanese slavery. I’m also interested in a broader way about the presence of blackness and brownness in England with a longer kind of timescale, going back to the Romans, and even before. But, you know, this association with English and Englishness and whiteness is a very new thing in the broader history of this island. I have used the figure of ‘the Brown Girl’ which re-occurs in English folksong to explore this forgotten ancient Black British history remembered only in the oral history of folksong.

You evidently bring together so many different images in your work to show how histories and cultural memories are intertwined. Could you talk me through ‘The Jumbee sugar cane and the Cutty Wren’?

The Jumbee sugar cane and the Cutty Wren, 2020 (Panel 2)

Imperial Employment, Shadowed, 2020 (Copy)

The piece included imagery of the Hampshire countryside with images of impoldered land in Guyana. When the Dutch colonised Guyana before the English, they tried to implement their system of land impolderment to gain more land for sugarcane. They claimed huge amounts of land from the sea and it was constantly flooding. There are still issues with flooding today; Georgetown, the capital, is below the sea level and with the climate crisis it is only going to get worse. Enslaved people were having to deal with awful living conditions in this context of flooding. Walter Rodney describes this vividly in his book about the history of Guyanese working people [1]. But also enslaved people would not only burn down sugar plantations during a rebellion. It was also a form of rebellion to purposefully flood fields of sugarcane so that they became unusable. So, there’s a double-edged nature to the flooding.

And then on top of all of that I was working with folkloric imagery from both Guyana and England. There’s an old folk song called the Cutty Wren that some argue became an anthem during the peasant’s revolt of 1381. The wren is the king of the birds because it flies the highest but it’s also the smallest. I think that’s symbolic of the nature of power. Cultural hegemony, state power, soft power, all these things that capitalism has in place to keep people in order. But at the end of the day when you look at it, there is a mad fragility there. It feels extremely potent and symbolic of the nature of colonial power. In a country like Guyana, there was a tiny plantocracy controlling millions of people. I was also working with Guyanese folklore, including the Jumbee and Baccoo, which are folkloric demons. I see these creatures of folklore as forms of residual colonial memory, and the memory of trauma is embodied through this demon.

So, there was a lot going on in this image and putting it on the steps of UCL was to place it where this imperialist ideology is embedded in neoclassical architecture, putting that history and that imagery on that architecture felt important.

You’ve referred to your own family several times. How does your own background shape your work?

Well, I guess, in different ways. In a sense, I just make work and think about things and occasionally refer to my own family history or family experience or my own experiences, without necessarily always being highly emotionally engaged. But then at the same time, I wouldn’t be thinking about this sort of thing if I wasn’t brought up in a family where, you know, we are all aware of the struggles which individuals in my family had to go through to be English or to exist in England. We’re all very aware of the history of colonialism in Guyana and the proud history of being black and British. And for that I am grateful.

Notes:

[1] Walter Rodney, A History of the Guyanese Working People, 1881-1905

You can see more of Austin Dean’s work here: www.mataioaustindean.com