In 1915, whilst the Great War raged between the Empires of Europe, British colonial rule was challenged in Nyasaland.

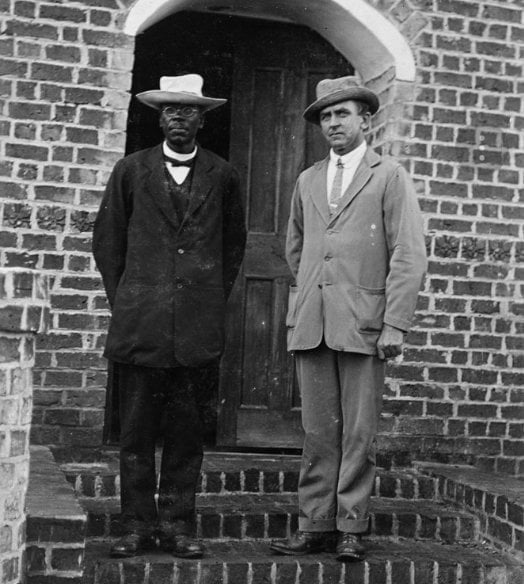

John Chilembwe was an unlikely revolutionary. Born in what would become the British Protectorate of Nyasaland, he was educated by Scottish missionaries and later trained as a baptist minister in America, where he received an education. Upon his return to Nyasaland in 1900, he opposed the colonial government and sought to advance African rights. Chilembwe was motivated to agitate against the British thanks to the brutal economic exploitation African workers faced in the plantation system as well as the political repression of Africans by the colonial regime. Both the colonial state and the Scottish Presbyterian missionaries considered Chilembwe to be dangerous, fearing his egalitarian ideals regarding racial equality which, if realised, would undermine the whole colonial system.

A.L. Bruce Estates

One plantation company in particular prompted his anti-colonial efforts; A. L. Bruce Estates. It was founded by the son-in-law of David Livingstone, the Scottish missionary who first pressured the British government to colonise central Africa in the name of Christianity. By the turn of the century, the company had passed to Alexander Bruce, the son of its founder. Bruce’s management was extremely brutal towards African workers. The company operated a harsh system of ‘thangata’ where African agricultural workers on the plantation had their rent paid in lieu of a wage and were therefore not compensated. They were often coerced into working through violence. Bruce himself was intimately involved in the running of Nyasaland, both as the company Director of one of the three largest land owners in the colony and as a member of the Governors Legislative Council. A staunch colonialist, Bruce fought for the interests of the European elite in Nyasaland and opposed any political, social or economic advancement for the African population.

Agitation against the regime

The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 also saw Chilembwe clash with the colonial regime further. Thousands of Africans were recruited as porters for the colonial armies marching against German East Africa (modern day Tanzania, Rwanda and Burundi) to the North. These porters were exposed to high levels of disease and mortality rates due to their poor working conditions, a fact that angered Chilembwe. Chilembwe was also appalled that Africans were being recruited to fight for a system in which they had no rights and in a war in which they had no real stake in. He advocated exempting Africans from military service on these grounds, to no avail.

Chilembwe’s outspoken advocacy for African rights did not go unpunished. A staunch opponent of the dominant Church of Scotland and their hypocritical Presbyterian missionaries, Chilembwe believed strongly in the need for independent African Churches. After returning to Nyasaland, he founded the Providence Industrial Mission in Mbombwe. He later founded a network of independent African schools, as well as a Cooperative Union, the Natives’ Industrial Union. Many of these churches were erected on privately owned European estates and Chilembwe won over many followers that worked on these estates, including A. L Bruce’s estate. Due to this and his opposition to any advancement for Africans, Bruce ordered his manager, a fellow Scot and a particular target of African resentment due to his enforcement of thangata, William Jervis Livingstone, to burn down all churches built on Bruce property by Chilembwe or his followers in November 1913.

The Uprising

From 1912 onwards, Chilembwe moved in a more radical direction, with his sermons becoming more militant accompanied by predictions of African liberation and the end of colonial rule. His exact motivation for opting for armed resistance is unclear. What is clear however is that after months of planning, the uprising began on the 23rd of January 1915. Chilembwe’s followers first launched a major attack on the main A. L. Bruce plantation at Magomero, killing Livingstone in the process. Whilst symbolic for them due to Livingstone’s brutish nature and violent reputation, the attack offered little military gain. They later unsuccessfully attempted to seize the weapons store of the African Lakes Company, another massive Scottish estate. They attempted to halt the spread of information of the uprising by cutting telephone lines. The uprising had one minor success when some rebels launched an attack on a small contingent of government soldiers but they were isolated and outgunned.

By January 26th, the colonial government had redeployed the Kings African Rifles and besieged Chilembwe’s church in Mbombwe, before successfully capturing it and demolishing the building. After a failed attack on a Catholic mission, Chilembwe resolved to flee into Mozambique to avoid capture. He was unsuccessful and was shot dead by colonial forces on the 3rd of February 1915. 300 rebels were imprisoned and a further 36 were summarily executed by the colonial state, with some of these being publicly hanged. The colonial authorities, frightened by the revolt, also instigated several arbitrary responses against the local African population, including a mass burning of huts. Though short and unsuccessful, Chilembwe’s revolt had sent a shiver down the spine of every colonialist in Nyasaland.

Chilembwe’s legacy

Chilembwe’s uprising served as an inspiration to anti-colonialists across the globe. He is today remembered as a National hero in Malawi and a pioneering anti-colonialist. The uprising also serves as an illustration of the deep involvement of Scotland in the British imperial project, with Scots gladly participating in the colonial oppression of Africans whilst they drained the wealth out of the company. After the uprising, Bruce successfully opposed any attempts by the colonial government to offset future uprisings by ending the harsh plantation system. He died in Scotland in 1954, his estates sold off due to poor management, his company 5 years away from insolvency and the independence of Nyasaland as Malawi only 9 years away.

Further reading

Let Us Die for Africa: An African Perspective On The Life and Death of John Chilembwe Of Nyasaland by Desmond Dudwa Phiri

Religion and Mythology in the Chilembwe Rising of 1915 in Nyasaland and the Easter Rising of 1916 in Ireland: Preparing for the End Times?. Studies in world christianity 23, no. 1 (2017) by Jack T. Thompson

Voices from the Chilembwe Uprising: Witness Testimonies made to the Nyasaland Rising Commission of Inquiry, 1915 edited by John McCraken

The extreme penalty of the law’: mercy and the death penalty as aspects of state power in colonial Nyasaland, c. 1903 47. Journal of Eastern African Studies Vol. 4, No. 3 (2010) by Stacy Hynde