In this exhibition, we examine the remnants of colonial detention camps in Kenya, focusing on Manyani Maximum Security Prison. We explore how Manyani’s design, purpose, and operation were deeply rooted in anti-blackness. The exhibition highlights how frameworks of environment, health, infrastructure, erasure, and resistance help us to understand how current models of imprisonment and anti-blackness are linked.

Research & Introduction

MBC’s investigation is centered around Manyani detention camp, situated in Kenya’s arid Tsavo National Park. Initially established in 1954 as a reception center to hold detainees in transit to other camps across the country, Manyani would later become one of the largest and most hostile detention camps during the emergency period. Former detainees have described it as ‘unbearable’, citing violent dust storms, poor sanitation, wild animals, overcrowding, and lack of food/water.

After Kenya gained independence, Manyani was converted into a state prison and remains one of the largest prisons in the country today. MBC’s exhibition explores how Manyani’s design, purpose, and operation were deeply rooted in anti-blackness. It highlights how these frameworks continue to sustain the prison system in Kenya today.

The exhibition explores five core themes: Infrastructural Anti-blackness, Ecology and Environment, Health and Welfare, and Erasure, and culminates by exploring how resistance in Manyani, just like resistance to anti-blackness today, is an ongoing, ever-present act.

Kenya – A Colonial History

Scholars estimate that British colonial forces set up and operated over 100 detention camps, works camps and emergency villages to support their campaign to retain control of Kenya in the face of a fierce independence movement in the 1950s. The British colonial administration used this network of camps – referred to as the ‘pipeline’ – to detain and torture hundreds of thousands of Kenyans with the aim of extracting confessions of allegiance to the Mau Mau independence movement.

After independence, many camps were turned into prisons and secondary schools which endure to this day. As a result of this repurposing, the migration of archives and the suppression of this history, memories of them have been almost entirely – and very deliberately – wiped out in both Kenya and the UK.

There is no evidence of pre-colonial prisons in Kenya. This system was a British importation and the number of prisons grew rapidly in the first decade of British colonial rule. Kenyans were being imprisoned through new by-laws and legislations introduced by the colonial government which Kenyans at the time would not have understood as offenses. European settlers were key drivers in the strengthening of judicial and prison powers. This paranoia intensified during the insurgency period. Throughout the colonial era, the punitive action inflicted by prison staff was often irregular, unregulated, and indiscriminate.

The Mau Mau insurgency was a major turning point in the history of detention in Kenya. Kenya was ruled under a State of Emergency from 1952, and prisons and detention formed a central part of Britain’s campaign against these ‘rebels’. In 1954, at the height of this conflict, the average number of Mau Mau detainees and prisoners numbered 71, 346.

Approach

MBC employed a multifaceted approach and utilized a variety of research methods to investigate the links between the past and present. The project activities included fieldwork to the former site of Manyani camp and present-day Manyani Maximum prison, oral history interviews with survivors, archival and desktop research in Kenya and the UK, and expert contributions during panel discussions. The nature of our methodology produced a series of multi-media outputs which we are pleased to present in the subsequent sections:

Field Work Visit – Manyani Camp

On 28th March 2023, the MBC team visited Manyani Maximum Security Prison in Tsavo Kenya. The team found remnants of structures constructed that were part of the original detention camp; they were also able to trace how these structures have evolved from the 1950s to present day through policies by successive post-independence governments.

Life in Manyani Camp – Field work documentary

Global Conversation – Anti Blackness and Colonial Detention: Past and Present

In this conversation MBC explored how British ideas of detention have been repurposed, re-used and maintained in different parts of the world. How have the physical, legal, and social infrastructure of detention been rooted in anti-Blackness? How does this manifest in the criminal systems in existence today?

“There were no prisons in Kenya before colonialism… systems of justice were more about recompense and retribution for the offenders… when the British colonial power came, prisons were one of the first things they brought… introducing the idea of punitive incarceration… Prisons in Kenya soon became places of abandonment and rejection by the society… which continues to be the case till today” – Patrick Gathara:

“The introduction of prisons, the policing, and new types of court systems were justified by the Europeans as part of the racist ‘civilising mission’… Prisons were seen to be more humane than a wide range of justice practices that were used by African communities before, which wasn’t the case.” – Katherine Bruce-Lockhart:

“The colonial powers wanted to keep certain populations out of the city… they wanted to control economic power… For a lot of these offences, officials could arrest people without a warrant of offence…allowing people unrestricted discretion to target people based on the way they look” – Kristen Peterson

Audience Responses

“ I am interested in how these precise punitive and carceral orientations remain pervasive in the present, particularly as technologies of anti-Blackness across geographies, in addition to African contexts. So that the colonial is not merely in the past, but an enduring condition across the so called “West”. As is the case with police violence. I am wondering what the relationship of these practices of detention to other legal infrastructures of extraction would be? I am thinking here, for instance, of laws such as the Witchcraft suppression act in Zimbabwe (settler Rhodesia) together with tax, mining and other laws regulating the human-animal-otherworld”

ATTENDEE

“The Language that is still retained within the administrative system lingers on the use of “Afande” is still in use today. This is a corruption of Effendi from the Turkish Ottoman empire “Falleni” is Fall in from british military parade! …this in built colonial legacy lives on subconsciously!” –

ATTENDEE

Guest Blog Series

MBC commissioned a series of blogs by global scholars and historians on the varied experiences of colonialism, racism, and the detention system under the British Empire.

-

Archiving Legacy of Resistance in Post Colonial Kenya: An Interview

Gizaw discussed legacy of detention centres in post-colonial Kenya, his work in the Kakuma Camp and the divide between community research and academic scholarship

-

Incarceration: Hashtag, Because, Colonialism

What my visit to Manyani Prison taught me about prison systems established in colonial Kenya and their impact on rehabilitation

-

Prejudice, Punishment, and Protest: The Carceral Experience under Colonial Rule in India

by Ashish Rawat The punishment must proceed from the crime; the law must appear to be a necessity of things,

Reflections

Infrastructural Anti-Blackness

c/o: Museum of British Colonialism

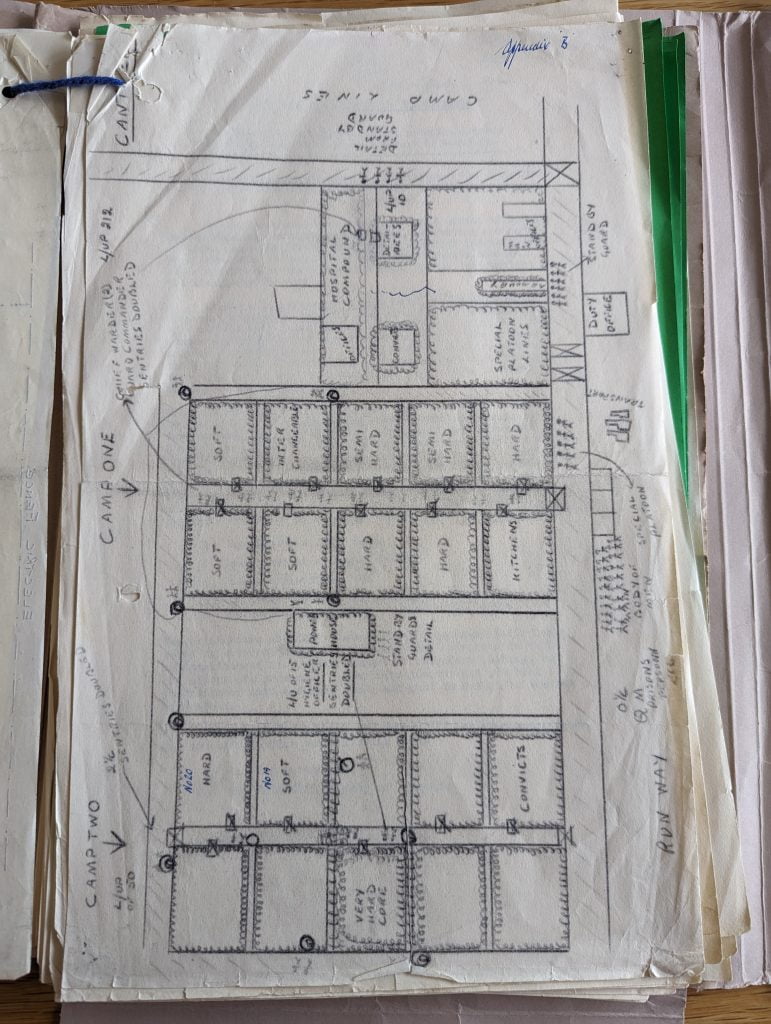

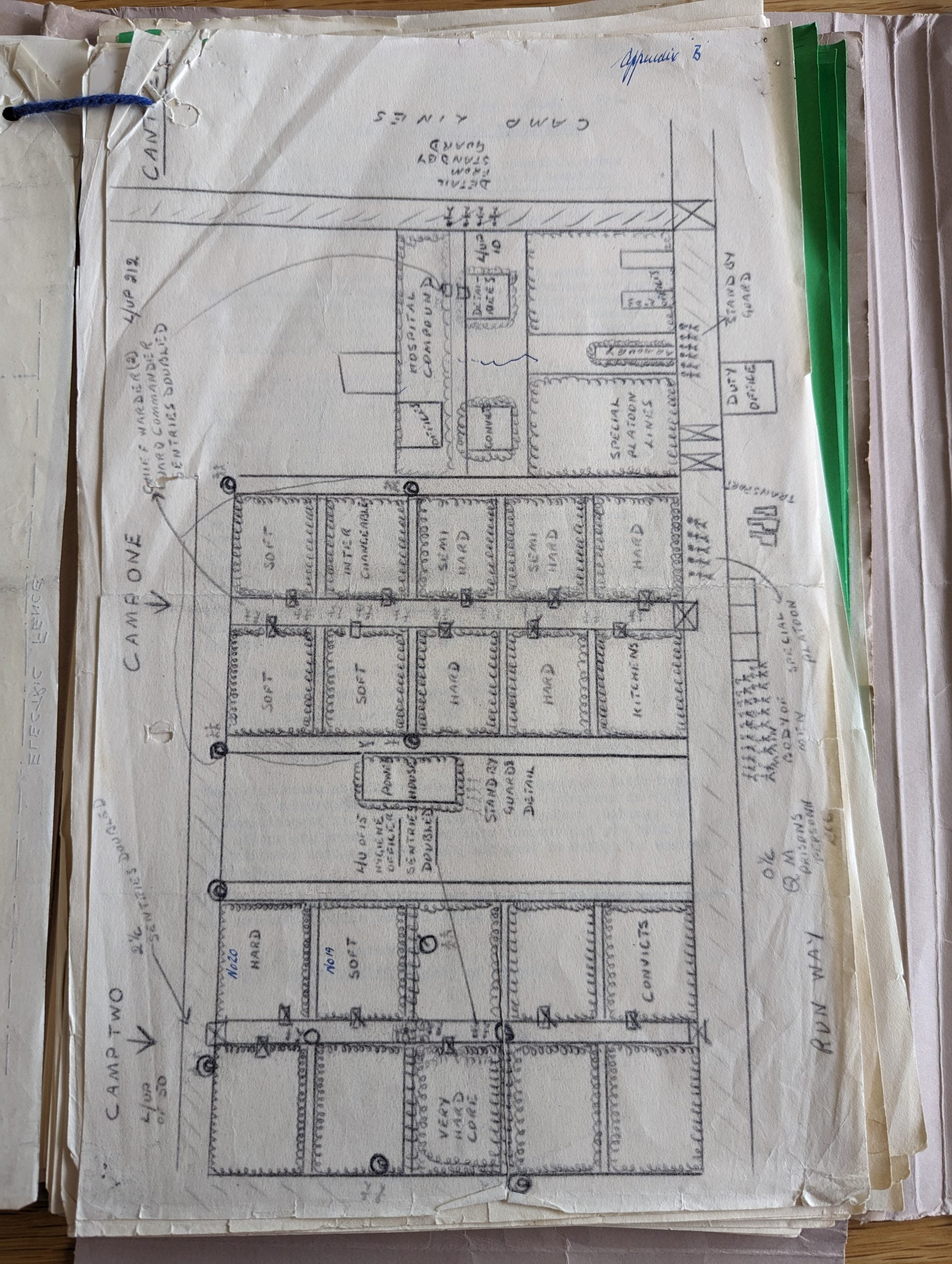

Kenya’s colonial detention camps and prison centers were built according to rigid systemic rules that shaped the architecture and layout of any related infrastructure. Everything from storage units to mass cells, isolation cells, utilities and recreational spaces was planned to serve the colonial state and disregard the human dignity of the detainees.

The infrastructural design of Manyani camp, and many others like it across the country, clearly shows how architecture was used as a main tool of dehumanization. Buildings with poor ventilation and scarce sanitary facilities housed almost twice as many detainees as they were meant to. A public health report from Manyani in 1954 stated that cells that were meant for 40 detainees, now had 60. This number likely increased as the emergency continued.

Detention facilities were also divided into compounds for the sake of isolating and controlling how detainees interacted with each other. Detainees were classified (black, gray and white) based on their conduct and their readiness to renounce the Mau Mau and be reformed . They would often be transferred from one compound to another to stop them from creating alliances and strong ties. Here, infrastructural design became

key method of social control that denied detainees the freedom of movement and the ability to gather, communicate and socialize.

The infrastructure of detention centers was inherently anti-black from the start. White and Asian camp officers had better living conditions than their African colleagues. One report mentioned that a tennis court and swimming pool was being built for European leisure activities. Meanwhile detainees were squeezed into overcrowded spaces and facing a typhoid outbreak.

“There were no prisons in Kenya before colonialism… systems of justice were more about recompense and retribution for the offenders… when the British colonial power came, prisons were one of the first things they brought… introducing the idea of punitive incarceration. Prisons in Kenya soon became places of abandonment and rejection by the society… which continues to be the case till today” – Patrick Gathara

To analyze the workings of colonial machinery is to face the ways in which everything was appropriated into colonial vision, landscape and brick and mortar became instruments used to advance colonial oppression. Today the very leftovers of these sites persist to further the colonial agenda and attest to its deliberateness.

Health & Welfare

c/o: Museum of British Colonialism

“It would be mild irony to state that welfare amenities are inadequate at [Manyani] for, in fact, such amenities do not exist at all.” – Welfare Report on Manyani camp, 25 June 1954

In today’s Kenya Prisons Service, it has been noted that the most significant challenges threatening the prison mandate include: overcrowding, unhygienic conditions, overstretched physical facilities, and insufficient professionals qualified to address the health needs in prisoners. This reality is nothing new. In the first year of Manyani camp operating, then as a holding camp for suspected Mau Mau members, these same issues were of a deadly presence.

In 1954, Manyani was built to house 6,000 detainees. Within months, it was reported that 16,000 detainees were being held there. Come May of that year, the camp commandant received a public health report containing concerning details. Prisoner latrine buckets were overflowing. Some were positioned near the camp’s kitchens. The compounds were infested with flies. Recommendations were made to improve these conditions if the camp was to go on to operate at a humane standard.

Overcrowded and packed into tight quarters with poor sanitary conditions, detainees were struck by a major typhoid epidemic. Despite several members of the Kenya government internally

denouncing the conditions in Manyani, Governor Evelyn Baring publicly denied any incidence of typhoid and maintained that the camp sanitation facilities were state-of-the-art, and that detainees had access to fresh water and sufficient medical care.

After news of the typhoid epidemic caused an outcry in the British media and among Labour MPs, Secretary of State for the Colonies, Alan Lennox-Boyd – following a highly publicized staged tour of Manyani – announced in the House of Commons that the epidemic was in no part a failure of the camp’s facilities or officers, but was due to detainees who had entered the camp already infected with the disease. He reported 63 typhoid-related deaths. Detainee’s tasked to bury the dead reported burying ‘six hundred bodies’.

The terrible condition of healthcare and sanitation in Manyani camp was not unusual among imprisonment centers across the empire; it is still common in prison systems today. Systemic under-resourcing coupled with the prioritization of punitive and carceral frameworks over basic human rights, remains a weaponized form of injustice and anti-blackness today.

Ecology & Environment

c/o: Museum of British Colonialism

The ecology and environment of Manyani detention camp was the most important thing in the selection of its location. Situated inside Kenya’s largest National Park, a place historically known for lions that preyed on humans, and extreme heat and dryness, the colonial rulers used the environment as a weapon against the detainees, separating them from their ancestral lands and throwing them into a harsh and unfamiliar setting.

Facilities were often overcrowded, beyond the intended capacity and the extremely hot seasons made it even more unbearable for inmates. After independence, Manyani camp was shut down and its infrastructure absorbed into the Kenya prison system. Today it remains one of Kenya’s largest and toughest prisons.

In 2023, MBC visited the prison to explore what sites from the former camp still remain today and how they are used within the current prison system. This hut, embedded with the signature colonial barbed wire insignia hanging over the roofs, today shelters more than 10 inmates at a time. The huts were constructed during the colonial era.

One of the guards mentioned that the environment itself punishes anyone who tries to escape, as nmates risk being killed by a wild animal. But lions

and elephants are not the only danger. When it rains, there is also a chance of other deadly animals like scorpions attacking the guards and inmates.

Manyani Maximum Prison covers a large area of land, but only about a third of it actually hosts the inmates. Most of it is empty land. New buildings at the facility are mostly for admin purposes. Part of the empty land holds the remains of the former camp.

Many of the structures were abandoned when the original detention camp was shut down. These ruins have now become part of the natural environment and they remain on the landscape like a scar across the cheek. There have been minimal efforts to preserve them and there are plans to create a museum that could possibly bring some money for the government and jobs for local people.

“Colonial arrest was inescapable and knew no clear territorial or legal boundaries; everyday life, from spirituality to indigenous agricultural practices and cultures, was criminalized as an extension of the ‘civilising’ mission” – Jackline Kemigisa

Manyani shows us how the brutal colonial logics of anti-blackness and violence still impact our systems today and how they are not only damaging to our minds and bodies but also persist in our environments and landscapes as well.

Resistance to Colonialism

c/o: Museum of British Colonialism

“The detainees… are completely uncooperative, insolent and obstruct every effort on the part of the staff to restore discipline… They have also openly stated… [they] are quite prepared to die.” Special Branch Report,

23 June 1960

Mau Mau detainees had a significant degree of organized resistance against prison guards at Manyani camp. As a ‘holding’ camp which was overpopulated, with a severe lack of amenities, controlled by largely untrained and ever changing guards, and a site of extreme brutality and interrogation, detainees sought to be as uncooperative as possible.

While this resistance was evident throughout the Emergency, it was the 1957 riot which sparked the most concern for the colonial state. In August of that year, camp warders entered Compound 16 on strict orders to reorganize detainees to suppress the building unrest among the most ‘hard-core’ individuals. When detainees refused to comply, the camp’s Special Riot Team Squad were sent in. In a similar vein, they were met with an organized and coordinated response from the detainees. Two warders were killed. Eight more were badly injured, one of whom was a European Officer. The detainees had made their own weapons, demolishing their huts for material.

It took the prison guards five days to regain control of the camp, but the resistance did not end there. Of the eleven detainees charged with murder, six were found guilty and sentenced to hang. During the trial, the detainees sought any means to disrupt the trial and the courtroom. The 1957 riot did not happen in a vacuum. Detainees had developed a number of methods to remain organized against state power and brutality. One of these methods included the Manyani Times, a secret circulation of newspaper clippings stolen from guards’ offices, as well as rumors and propaganda, designed to compel detainees to battle on.

Detainee resistance in Manyani forms part of a long history of resistance to colonialism, police violence and anti-blackness around the world. By looking at Manyani’s history in the wider context of global trends, we can learn how strategies of cooperation, imagination, innovation and intellectual development have supported black resistance and how they can keep doing so against many challenges.

ERASURE & – ANTI BLACKNESS

Ain’t I to be remembered?

Of the enabling establishments of coloniality, is the persistence of minimising human life to statistics and thus equating the victims of violence to static lifeless numeric. Manyani, as a site of violence, to-date persists in the use of statistics to erase the humanity of those that this site has jailed, killed and displaced. As established, Manyani’s locale was intentionally designed to displace and ensure those held within its confines are erased and ultimately forgotten.

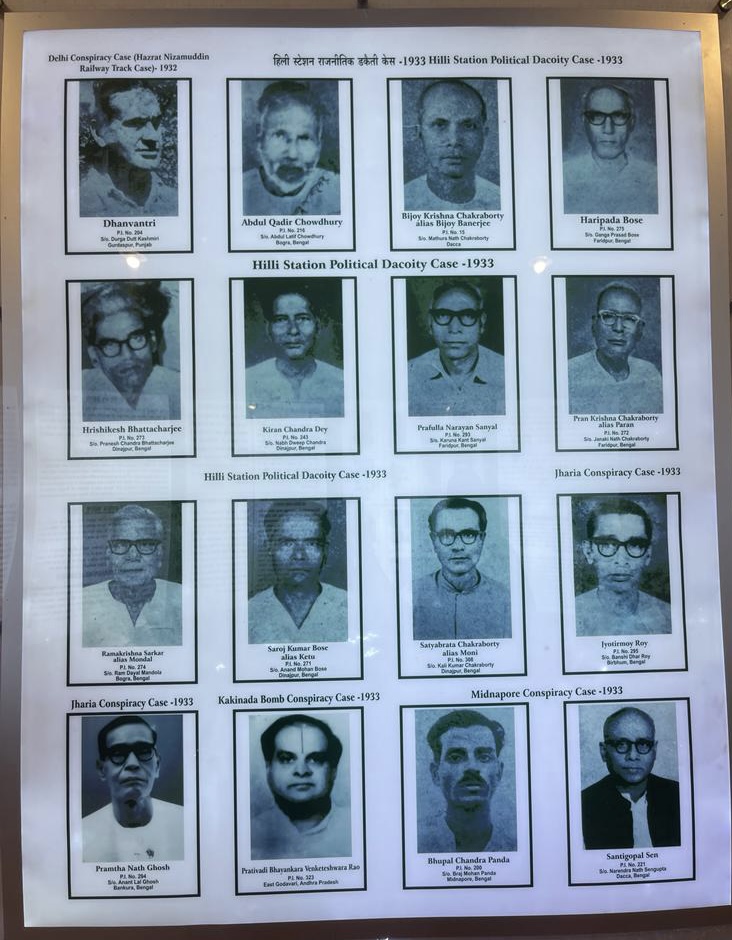

In these ‘othered’ sites of displacement, basic human life is minimised to a statistic – often the prisoner number. A tool that seeks to establish the immanence of coloniality and insignificance of human life within these epicenters of violence.

Other-ing and the congress of forgetfulness

Outside the city and urban life – taken away from humanity and limiting those who you love and those who love you from seeing you – a mechanism to disrupt the sanity of the prisoner and build in the erasure of ‘the humanity’ from the human. The prisoner with a face and name slowly turns into numerics. Names become oft-forgotten memories even to those within Manyani and the larger colonial machinery and all that remains recognised is the placed numerics.

In these ‘othered’ sites where violence, carcerality, and punitive punishment are the order of the day, the name of the person, their gender, and their identity – however fragile and transitional – becomes a site of invasion and disruption.

For colonialism is established through crude power and the intent to conquer, therefore under these mechanisms of violence, even the prisoner’s name is taken away and he is left bare, with only numerics to prove humanity. Therefore, the psychoanalysis of these ghost towns come back every so often to haunt the Kenyan people.

To date, the British colonial machinery has guarded and denied Kenyans their histories and made them near impossible to access by colonised demographics. From destroying these sites of violence to destroying imperative documentation that proves this violence was met – statistical erasure has become an incessant tool for empire to control and guard, the legitimacy of which is slowly crumbling.

The persistent statistical invisibility guided by this intentional erasure, disrupts the collection of data to establish the size of colonial wreckage, displacement, and horrors. While we look for the human elements to combat this erasure, this erasure builds on disruption of existence – while we seek to remember we are forced to forget.

Manyani, as a site of persistent coloniality, has now been re-established as a Maximum Security Prison – the epistemologies of violence persist – and again, the name is taken away and is replaced by numerics. A continuous blinding of human suffering through the statisticalisation of human life, that ultimately erases the human from the ‘humanity’.

As has been tried and tested in these camps, it is easier and more efficient to control and conquer lifeless, emotionless, and static binary numbers than it is human lives.

Exhibition Launch

On 15th September 2023, MBC launched this exhibition at SOAS, University of London. The exhibition brought together our research, fieldwork, and online events looking at colonial detention through the lens of anti-blackness, with a research video, specially commissioned artwork, 3D model, and references from our Global Conversations event and from our guest blog posts.

Acknowledgements

MBC would like to thank Proffesor Awino Okech and the exhibition team at SOAS for the space, resources and opportunity to reflect on this subject. As we endeavor to expand our practice, we are grateful for the new avenues in which we continue to deepen our exploration of colonial legacies and how they remain embedded in our lives today.

While it may sometimes feel that the work is hard and unending, we take heed of Mariam Kaba’s words that ‘hope is a discipline’ and we continue to have hope that this work may resonate with many in Kenya, UK and across the globe.

We would also like to thank the Kenya Prisons Service for facilitating access and safety during our trip to Manyani Maximum Prisons. We extend our gratitude to all the guest speakers, contributors and artists who agreed to lend their talent and expertise to this project.

This research and exhibition has been put together by MBC team members, Beth Rebisz, Hannah Mclean, Freya Samuels, Chandini Jaswal, Chao Tayiana Maina, Suhayl Omar, Linda Ngari and Anthony Maina.