In this installment of Paper Trails, MBC’s Andrea Potts spoke with Kremena Dimitrova about using comics to represent colonial histories. Kremena is an illustrator-as-historian, storyteller, lecturer in Visual Culture, and practice-based PhD researcher in Visualising History at the University of Portsmouth.

Andrea: It’s lovely to meet you. What do you research?

Kremena: Visualising histories of migration through comics with a focus on untold, hidden, forgotten, and marginalised narratives of colonialism, slavery, and statelessness. When it comes to archives, there are a lot of limitations in terms of whose history and whose stories are deemed important. And on top of that, archives are inaccessible to many people. Even if certain histories are archived, it does not necessarily mean that they can be easily accessed. You often have to be affiliated to a particular institution, for example. I regard my artistic work to be a form of comic-based activism that makes colonial histories and legacies visual and therefore visible. My approach is rooted in storytelling, creativity, collaboration, and co-creation.

My approach is rooted in storytelling, creativity, collaboration, and co-creation.

I am doing a practice-based PhD at the University of Portsmouth. I bring together comics, map-making, and poetry in my work. Artistic interventions can make visible colonial histories that are not represented in traditional ‘biased’ archives.

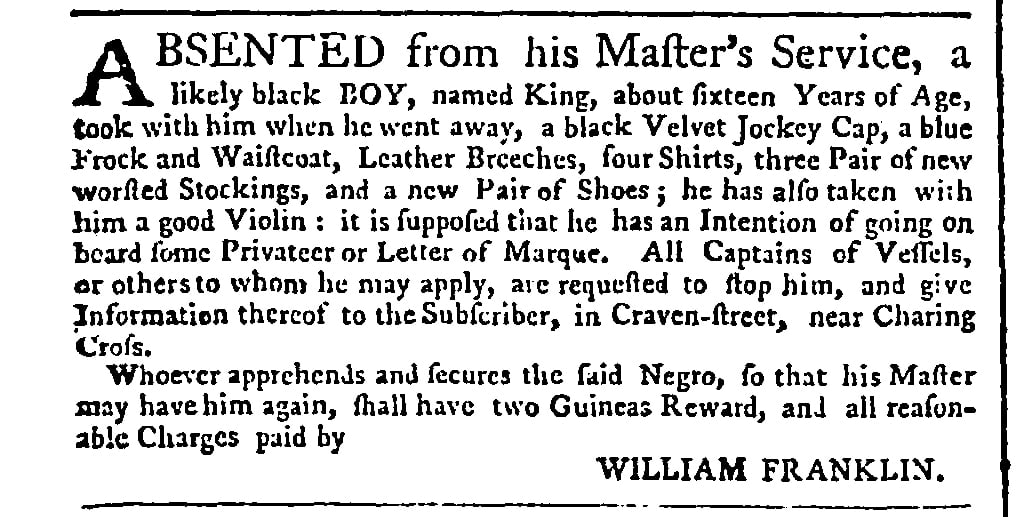

I decided to undertake this research while working as an illustrator in residence at Benjamin Franklin House, a biographical museum in London. I worked on a project which entailed visualising the life and work of Benjamin Franklin in London between 1757 and 1775 through working with younger people and children. As part of this, I started to think about the ‘hidden stories’ that the museum did not focus on. This included the fact that Franklin had come from the American colonies to London with two enslaved people. One was an eleven-year-old boy called John King. Through researching the database Runaway Slaves in Britain: bondage, freedom and race in the eighteenth century by the University of Glasgow, I discovered that after being brought to London as a slave, within one year, John King had escaped to Suffolk, East Anglia. I found two adverts calling for his return. We don’t know much more about him apart from that he had been helped by a woman who had taught him how to read and write and to play musical instruments. And then he disappears from the historical record. Even Benjamin Franklin stopped writing about him. I was interested in reimagining and visualising what had happened to him through comics, maps, and poetry. So, this is one of my case studies in my PhD.

A: I’m interested in the role of imagination in making colonial histories visible. Could you speak more about what this entails for you?

K: My work stems from archives and from narratives that have not been archived. I make what is referenced in the archive visual and I also expand upon those references. So, for me, John King’s story is one of self-emancipation and freedom. We can shift the focus of his narrative to something that is inspiring. Visual media means that I can humanize John King. He is not simply represented as a runaway slave in an advert. He is a real person and not a mere statistic.

Visual media means that I can humanize John King. He is not simply represented as a runaway slave in an advert. He is a real person and not a mere statistic.

It’s also not just me interpreting and imagining; I co-create my work with children, young people, and communities. So, my work reflects the imagination and ideas of many different publics. In workshops with young people, I share excerpts from archives, and we work together to creatively respond to them by overlaying them with oral histories. Some participants create drawings, while others write down their thoughts and ideas. In a way, my role is a facilitator and designer who pulls together all these different elements into a coherent and cohesive narrative whole. Often participants share very personal responses to histories of colonialism, slavery, and migration. I do this too, being an immigrant myself.

A: Why comics?

K: Well, comics are often seen as a form of resistance. There is a long history of comic-making as resistance, challenging the status quo and the overarching master narratives. It’s also a storytelling medium that is accessible, especially to younger people. I find that comics, because of their fragmented nature, are a good way to share micro-histories and fragmented narratives, in my case, the life of John King. The young boy’s comic story is a way into a larger story. We can gain so much from focusing on the ‘smaller’ stories that are so often ignored.

You can read about John King in:

Legacies of Slavery and Contemporary Resistance – Cambridge Scholars Publishing

Comics and Migration: Representation and Other Practices – 1st Edition (routledge.com)