by Christopher Michael Roberts

The British Empire was always and everywhere propped up by violence. That violence took many different forms, across time and place. At times it took the form of direct suppression, extra-judicial killing, terrorism and dispossession committed by military and paramilitary force.[1] At times it took the form of the power to decide who would and wouldn’t be allowed to speak on behalf of colonised populations. Everywhere and throughout (and beyond) the empire’s duration, it took the form of racist laws and policies unevenly distributing rights, justified by a host of ideological arguments which were deployed and adjusted as local and global circumstances and balances of power dictated.

This contribution is concerned with another aspect of British colonial violence and power: the institution of an extensive set of laws and policies designed to expand executive power and to suppress any and all modes of popular resistance. While racially differentiated in terms of the force with which they were deployed, these modalities were as much a product of metropolitan as colonial experiences, highlighting the inextricably interrelated nature of domestic and colonial struggles over governance.

While the history of such measures may be traced far back in time, certain moments were particularly fertile. The late eighteenth century was one such period, in which concern with rising republican and/or democratic sentiment led to the creation of the Home Office, the institution of treason and sedition prosecutions against those seen as challenging the existing regime, the creation of paramilitary groups oriented towards the direct infliction of violence against such ‘radicals’ and the passage of a range of new suppressive laws.[2] Later developments in repressive legality may also be traced to the manner in which emergency legal orders congealed into more regularised repressive laws and institutions over the course of the nineteenth century, including through the intermediary device of ‘peace preservations’ laws in particular.[3]

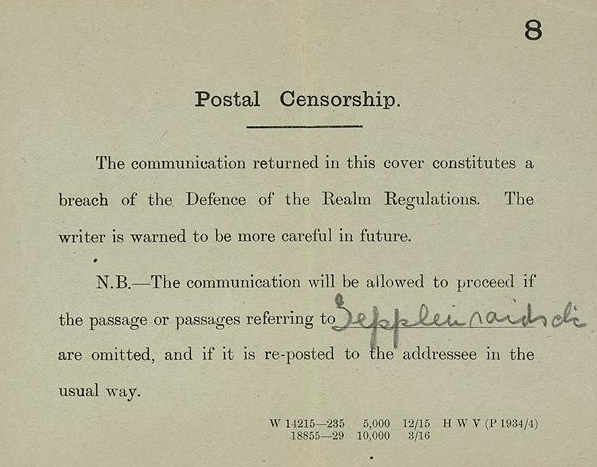

While these earlier periods were significant, they pale in comparison, in terms of the legal legacy they left behind, to the developments that took place in the early twentieth century. The First World War did not inaugurate a conceptually or ideologically new approach to governance in Britain, as all the relevant directions of travel were underway before its outbreak.[4] Nonetheless, the First World War provided the perfect moment of political opportunity in which an extensive array of repressive measures could be, and were, put into place, under the broad authorization of the Defense of the Realm Act (‘DORA’). The new repressive powers authorized and deployed under the DORA are too extensive to document fully in a brief space—the sixth edition, issued in August 1918, ran to more than six hundred pages.[5] Among the components of the DORA regime were measures allowing for control over the movement and residence of the population, for internal removal and external expulsion, for extended powers of search and arrest, for the surveillance, banning and/or penalisation of meeting and assemblies, and for limiting freedom of expression and communication, including by penalizing the spreading of ‘false news.’ While a foreign threat was used to justify the implementation of such measures, they were almost entirely not directed against a foreign but rather a ‘domestic’ enemy. In Britain, pacifists and socialists constituted the principal groups targeted for summary trials and arbitrary detention under such measures.[6]

The implementation and use of such measures did not end at Britain’s borders, however. Rather, similar measures were deployed around the British Empire. In Ireland, the DORA regulations were employed directly, inter alia to detain thousands of suspected Sinn Féin members.[7] In India, DORA had a direct analogue in the form of the Defense of India Act (‘DOIA’), under which nine high-profile conspiracy trials were heard, leading to twenty-eight death sentences, and which, together with the Ingress into India Ordinance, was used to authorise thousands of further detentions and internal travel bans as well.[8] In Egypt martial law was employed shortly following the outbreak of the war, and protests suppressed through often lethal force. In Sudan, martial law was already in effect, having been left in operation following the 1898 British conquest. In Hong Kong, emergency law too was deployed, under the authorising power of 1896 and 1916 Orders in Council. Unrest in Ceylon, South Africa and Nigeria also led to martial law being declared at various points over the course of the war, under which protests were violently repressed and numerous individuals detained either without any process at all or following summary proceedings. Anti-colonial resistance in Nyasaland was crushed with brutal force as well.[9] Emergency governance was employed in East Africa too, where it was used to reinforce and tighten the harsh forms of labor control developed in the pre-war decades, including to force many into forced labor in support of the East African war effort, in the course of which estimates have suggested around 100,000 died.[10]

The end of the First World War did not mean an end to the use of these measures. In Britain, this was dramatically illustrated by the 1918 ‘Termination of the Present War (Definition) Act,’ which extended the war as a matter of law through the end of August 1921. The purpose of this measure was simply to enable emergency laws brought into effect during the war to remain on the books, in order to fend off domestic socialist protests. The DORA regulations and similar measures brought into effect under the 1920 Emergency Powers Act, together with deployments of the military, were used to suppress several mass strikes in the following years, in the course of which further extensive arbitrary detentions took place.

Similar measures were also taken around the empire in the war’s wake. In Ireland, emergency law was used to authorise thousands of detentions of suspected anti-colonial activists. In India, the Anarchical and Revolutionary Crimes Act, better known as the Rowlatt Act, was brought into effect in 1919, helping lead to the infamous Jallianwala Bagh/Amritsar Massacre, alongside which hundreds were arbitrarily detained as well.[11] In Egypt, nationalist protests were met by collective punishment in which hundreds were killed; in Sudan too, resistance was met with attacks on civilians. The collective punishment of civilians, including as carried out by and in some ways as training for Britain’s new air force, took place in the Punjab, the Northwest Frontier, Afghanistan, Somaliland and, most extensively, Iraq as well.[12]

The story was largely similar in the Dominions as well as in Britain’s largest and most influential settler colony, the United States. While the repressive legal framework adopted during the First World War was nowhere near as extensive in the United States as in Britain, the Espionage and Sedition Acts were cut from a similar cloth to the DORA regulations. While similarly justified in terms of the need to fight an external enemy, they too were deployed to target domestic dissidents, including labor activists above all.[13] In the United States and Australia during the war, and in Canada immediately afterwards, mass trials were also deployed to suppress labor organisers, including the Industrial Workers of the World in the United States and Australia, and the analogous One Big Union in Canada. The United States was also the site for the largely UK-funded trial of the Ghadarites, an anti-colonial organization formed with the aim of fighting British occupation of India.[14]

Such are the broader parameters of the repression deployed in Britain, the British Empire and the British settler colonial world during World War I and in the postwar period. While it is impossible in a brief space to delve into the innumerable details, a few illustrative cases might be noted, to provide a further picture of events closer to the ground. In the United States, illustrative of the anti-worker deployment of repressive legality in the postwar years were the ‘Palmer raids,’ named after Alexander Palmer, the Attorney General who authorised them. The first Palmer raids began on 7 November 1919—the second anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution—with a raid on the headquarters of the Union of Russian Workers in New York. Over the course of the raids more than one thousand persons were assaulted and arrested around the country, and several hundred arbitrarily detained for longer spells. Two-hundred and forty-nine aliens were deported following the raids as well, including Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman, well-known leaders in the anarchist community. Another set of Palmer raids took place in January 1920, in which thousands more were detained. When called before Congress to explain the raids, Palmer argued—in language in this case deployed in the domestic context in the United States, though its parallels could be found everywhere around the empire, employed relative to socialists and anti-colonial activists alike—that he had been fighting against “poisonous theories” and “alien filth” which had “infected … [the] body of labor … [like] the presence of diseased tissue in the human body;” express[ed] his fear that “the continual inoculation of poison virus of social sedition, poisonous to every fiber and root, to every bone and sinew, to the very heart and soul” would lead to “the revolutionary disease;” … [and] describ[ed] the radicals against which the Bureau acted as consisting

of “idealists with distorted minds,” including “many even insane,” “professional agitators who are plainly self-seekers,” and “potential or actual criminals whose baseness of character leads them to espouse the unrestrained and gross theories and tactics of these organisations” …[15]

The United States was not the only part of Britain, the British Empire and the British settler colonial world in which supporters of workers’ rights were met by such treatment, however. Similar references to “aliens” and “agitators” were used by British colonial authorities in Nigeria before and after the First World War to describe Nigerian lawyers who challenged official decisions.[16] In Nairobi, Kenya, Harry Thuku founded the East African Association in 1921. A central component of the association’s work was opposition to the extremely restrictive kipande system through which workers’ mobility and work options were sharply constrained and controlled. The British colonial authorities, and most of all Kenya’s white settler farmers, were not happy with these engagements, however, and on 14 March 1922 Thuku was arrested. His supporters thereafter conducted mass protests; in response, the police, supported by white vigilantes, opened fire, killing dozens. Shortly thereafter, Thuku was exiled without process to the Northern Frontier Province of British Colonial Kenya, where he would remain for the next eight and a half years, and the East African Association was banned.[17]

The mid-1920s saw clashes between workers and the state intensify in Britain, the British Empire and the British settler colonial world. In the United Kingdom, the largest strike in the country’s history was agreed to at a meeting of the Trade Union Congress attended by close to 1,000 delegates of 137 unions representing 3,600,000 persons, and began on May 3, 1926.[18] The government responded by declaring a state of emergency, deploying the military and a huge force of special constables, and utilizing the heightened capacity for the output of propaganda it had developed before and over the course of the First World War to the fullest. More than 8,000 people were arbitrarily detained and charged with various violations of emergency regulations and the common law over the following months, before being tried in summary proceedings before partisan magistrates.[19]

The metropole was not the only part of the British Empire that faced large-scale strikes in the mid-1920s, however. Rather, Hong Kong too saw a massive general strike, spurred by the killing of several protestors through the use of excessive police force in Shanghai, followed by the killing of a larger number of protesters in Canton. Among other demands, the strikers called for an eight-hour workday, the abolition of child labor, freedom of expression, greater political voice, and an end to racial discrimination. Following the outbreak of the strikes, which were accompanied by a boycott of British goods in Canton, the British government in Hong Kong banned all organizations promoting strikes, granted the police discretionary power to ban assemblies, issued regulations allowing for the imprisonment of dissenters following summary conviction, and deported anyone deemed a striker or ‘idler.’ For his part, Governor Reginald Stubbs said of the strike “[t]he present movement cannot be called a strike … the movement is nothing less than an attack on existing standards of civilization as represented by Hong Kong … we have to realize that we are faced with a deliberate attempt to destroy, in the interests of anarchy, the prosperity and the very existence of the community.”[20] Whether in the United States, the United Kingdom, Kenya or Hong Kong, in short, calls for greater rights for workers were not met with a sympathetic ear, but rather by state violence and repression, while those calling for such rights were treated as belonging to a lesser category of persons, outside the ‘community’ that was to be defended.

In sum, the period between 1914 and 1927 saw the massive development and deployment of new and intensified forms of repressive legality, which were used to target and suppress labor, socialist and anti-colonial activists alike. The innovations of the period have remained a key part of the global legal order since. In numerous jurisdictions, laws and ordinances from the period are still on the books, and remain periodically deployed to silence dissent. Elsewhere, while new laws have been adopted, those laws hew very closely to the original model set. While one component of the colonial legacy may have been overcome, therefore, when formerly colonized states became independent, the legal model that underpinned colonial control has with unfortunate frequency remained a key part of many states’ systems of public order control to the present day.

[1] See, e.g., from an extensive array of sources, Caroline Elkins, Britain’s Gulag: The Brutal End of Empire in Kenya (2005); David Anderson, History of the Hanged: The Untold Story of Britain’s Gulag in Kenya (2005); Matthew Hughes, Britain’s Pacification of Palestine: The British Army, the Colonial State, and the Arab Revolt, 1936-1939 (2019).

[2] See Clive Emsley, “Repression, ‘Terror’ and the Rule of Law in England During the Decade of the French Revolution,” 100 English History Review 801 (1985); John Barrell, Imagining the King’s Death: Figurative Treason, Fantasies of Regicide 1793-1796 (2000); John Barrell & Jon Mee eds., Trial for Treason and Sedition (2006); Christopher Michael Roberts, “Experiments with Suppression: The Evolution of Repressive Legality in Britain in the Revolutionary Period,” 43 Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review 125 (2020).

[3] See Christopher Michael Roberts, “From the State of Emergency to the Rule of Law: The Evolution of Repressive Legality in the Nineteenth Century British Empire,” 20 Chicago Journal of International Law 1 (2019).

[4] See David French, “Spy Fever in Britain, 1900-1915,” 21 The Historical Journal 355 (1978); Bernard Porter, The Origins of the Vigilant State (1987); Thomas Fergusson, British Military Intelligence 1870-1914: The Development of a Modern Intelligence Organization (1984); R.J.Q. Adams & Philip Poirier, The Conscription Controversy in Great Britain, 1900-1918 (1987); Barbara Weinberger, Keeping the Peace? Policing Strikes in Britain, 1906-1926 (1991); Richard Vogler, Reading the Riot Act: The Magistracy, The Police and the Army in Civil Disorder (1991); Christopher Michael Roberts, “Forging the National Security State: Public Order Legality in Britain, 1900-1918” (forthcoming in Unbound: Harvard Journal of the Legal Left).

[5] See Defence of the realm manual (6th ed., 1918).

[6] See Brock Millman, Managing Domestic Dissent in First World War Britain (2000); Keith Ewing & Conor Anthony Gearty, The Struggle for Civil Liberties: Political Freedom and the Rule of Law in Britain, 1914-1945 (2001); Rachel Vorspan, “Law and War: Individual Rights, Executive Authority, and Judicial Power in England During World War I,” 38 Vanderbilt Journal of Transnational Law 261 (2005).

[7] See Ewing & Gearty, The Struggle for Civil Liberties.

[8] See Mark Condos, The Insecurity State: Punjab and the Making of Colonial Power in British India (2017).

[9] See Christopher Michael Roberts, “The Age of Emergency,” 20 Washington University Global Studies Law Review 99 (2021).

[10] See Geoffrey Hodges, The Carrier Corps: Military Labor in the East African Campaign, 1914-1918 (1986).

[11] See Kim Wagner, Amritsar 1919: An Empire of Fear and the Making of a Massacre (2019).

[12] See Priya Satia, “In Defense of Inhumanity: Air Control and the British Idea of Arabia,” 111 American History Review (2006).

[13] See Christopher Capozzola, Uncle Sam Wants You: World War I and the Making of the Modern American Citizen (2008).

[14] See Maia Ramnath, Haj to Utopia: How the Ghadar Movement Chaarted Global Radicalism and Attempted to Overthrow the British Empire (2011); Gajendra Singh, “Jodh Singh, the Ghadar Movement and the Anti-Colonial Deviant in the Anglo-American Imagination,” 245 Past & Present 187 (2019).

[15] Christopher Roberts, “The Global Red Scare and the Anti-Worker Repressive Model, 1913-1927,” 5 Cardozo International & Comparative Law Review 415, 477 (2022), citing Regin Schmidt, Red Scare: FBI and the Origins of Anticommunism in the United States, 1919-1943 89-90 (2000); Capozzola, Uncle Sam Wants You at 203.

[16] See Bonny Ibhawoh, “Stronger than the Maxim Gum: Law, Human Rights and British Colonial Hegemony in Nigeria,” 72 Africa: Journal of the International African Institute 55 (2002); Bonny Ibhawoh, Imperialism and Human Rights: Colonial Discourses of Rights and Liberties in African History (2006).

[17] For more, see Harry Thuku, Harry Thuku: An Autobiography (1970); John Lonsdale, “Thuku, Harry,” in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2003).

[18] Ewing & Gearty, The Struggle for Civil Liberties at 157.

[19] See ibid at 161-209.

[20] For more, see Richard Klein, “The Empire Strikes Back: Britain’s Use of the Law to Suppress Political Dissent in Hong Kong,” 15 Boston University International Law Journal 1 (1997); Michael Ng, Shengyue Zhang & Max Wong, “‘Who But the Governor in Executive Council is the Judge?’ – Historical Use of the Emergency Regulations Ordinance,” 50 Hong Kong Law Journal 425 (2020).

Professor Christopher Michael Roberts is an Assistant Professor, Assistant Dean (Undergraduate Studies) and LLB Programme Director in the Faculty of Law at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Among other themes, Professor Roberts’ research focuses on the historical evolution of public order legality in nineteenth and twentieth century Britain, the British Empire and the British settler colonial world. He is currently working on a book tentatively titled “Anarchism, Espionage, Syndicalism and Sedition: The Construction of the Anti-Worker State, 1880-1927.”