BY CHANDINI JASWAL

PROLOGUE

There is a popular folk melody in Punjab sung during weddings:

“Tere mukhde da kala-kala til ve,

Mera kat ke le gaya dil ve,

ve mundiya Sialkotia…ve mundiya Sialkotia..”

“The black mole on your face has swept me off my feet,

o handsome one from Sialkot!”

Such is the prominence of this city -Sialkot – in the history and heritage of Punjab. This is the Partition story of one such proud Son of Sialkot.

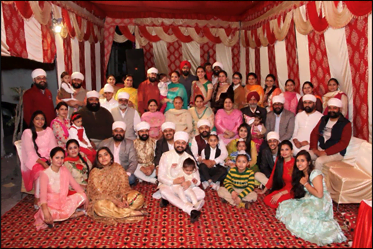

“Should I speak in Punjabi or Hindi?” Ripdaman uncle enquired as we began the video call. I replied that he could speak in both and sheepishly added my inability to speak fluent Punjabi. He smiled and began speaking in the Hindi-Punjabi composite dialect that I am familiar with: “My name is Ripdaman Singh. We belong to village Khokhar, tehsil Narowal, district Sialkot. It may be Pakistan for you today, but for us, Sialkot (and Punjab) will always be home.” Even with the video call, I saw that Uncle was not very old. When I enquired about his age, he replied he was sixty-two and had lived all his life in Delhi—he had never been to Sialkot, yet his sincere love for the city was unmistakable. Uncle smiled and began narrating the Partition story of his family.

A TRAGIC FAREWELL

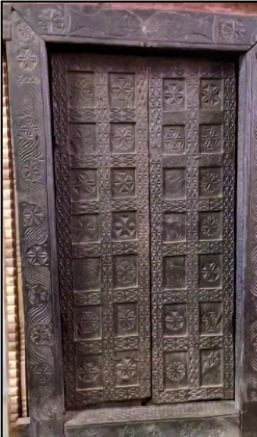

“My father Havela Singh (1920-1997) and grandfather Sunder Singh (c.1885-1978) were skilled mistris (carpenters) in Sialkot,” Uncle remarked. “Have you seen those wooden doors from olden times with those intricate flowers and leaves designed on their periphery? My family used to design those. Not long ago, I remember seeing those tools: small in size with a sharp blade on its end. Every little detail was done by hand then.” His father Havela Singh had a big family. Havela Singh lived with his wife, father, mother, three brothers and three sisters. It was, in his words, “an ordinary middle-class household”. “Even though my grandfather had hardly received any education, my father had completed his matriculation, which was a huge deal in the village back then.” Uncle’s parents had two children at the time of Partition.

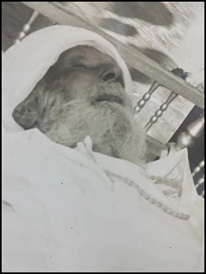

“When my family was fleeing from Khokhar on foot, my elder brother, who was one and a half months old at the time, died along the way. In his words, “Mother’s milk, owing to excessive heat and hunger, had turned into poison.” Uncle became quiet for a moment, and words failed me too. He continued, “Then the saddest thing happened: since it was impossible to have last rites in the middle of the journey, as they crossed river Ravi… phir dariya vich he sut ta usse time (they threw [the body of the baby] in the river at that moment).” Uncle’s family had walked for three days continuously along the Amritsar-Lahore transit route. After staying for a couple of days in a government refugee camp, they went to Batala on foot (nearly 40 km from Amritsar) and found an evacuee house. “My mamaji (maternal uncle) had come to India much before we did. He was employed as the chief engineer in a sugar mill in Rae Bareli (in present-day Uttar Pradesh). He helped my family tremendously. He had called my father along with my Chachaji (paternal uncle) to work with him in the mill…”

Uncle continued,

“From there my father and chachaji went with my mamaji to Amroha, Bulandshahr (cities in present-day Uttar Pradesh, India) and finally reached Delhi in 1959. My grandfather was awarded a hundred Gaz (ninety-one square-metres) plot in Delhi by the Compensation and Rehabilitation committee.”

I enquired if anyone from his family ever returned to Sialkot. In 1957, the governments of India and Pakistan had allowed free mobility to people on both sides. Uncle noted, “When my family had left Sialkot, they were certain that they would return someday and thus intentionally took nothing with them apart from some money. Finally, when the border rules were eased in 1957, my grandfather went back to Khokhar (their village in Sialkot) to his home. He had noticed that their house was intact. However, their family name had been erased from the front wall. While my grandfather could not bring back any of his belongings since the new owners had assumed possession of those, my grandmother had hidden silver coins in the cowshed at the back of the house. She had buried the coins in the straw fed to the cows. My grandfather took a local police officer with him, retrieved that urn filled with silver coins and brought it back to India. It was worth ₹1,100 then, which was a lot. With that money, my grandfather bought another plot of land about 400 gaz in size, a 100 gaz for each of his four sons. It was later that the struggle of our family for survival began.” By 1957, the family left their traditional livelihood of carpentry and had taken up other jobs.

‘THE HOME’ NEVER LIVED IN

“Since it was impossible to have the last rites in the middle of the journey, as they crossed the river Ravi… they threw [the body of their newborn baby] in the river at that moment

Ripdaman Singh, the narrator on his parents’ flight post partition

Ripdaman uncle, born much later (b.1960) fondly recalls his family’s memories of Partition. “Despite the tragedy, my parents and grandfather would often remember life before 1947 and and they especially missed their village. My parents would narrate vivid stories about Sialkot, their house, neighbourhood, and the fields. As children, my siblings and I would close our eyes and imagine what this ‘home’ looked like – even now, fifty years later, as I narrate my story to you, the same image of Sialkot I imagined as a child, springs up in my mind.”

When I asked Uncle if he had ever heard of any episodes of communal tension from his family, he remarked, “Although the rumour was rife that all territories cis-Ravi [a river in North India, Panjab] would fall into Pakistan, including Sialkot, my parents did not move earlier. They were helped by local Muslims, who kept night vigil as communal tensions in Sialkot rose. Khatra unha toh se jehde idron aiye se (The threat was from those refugees who came from India to live in Pakistan).”

After Ripdaman uncle finished narrating his family’s story, I requested him to share his thoughts on the experience. Uncle eloquently replied: “My family may have been uprooted from the city, but we have certainly not forgotten the land. Asi hun we uss zamin nal judey haan. (Even today, we are attached to that land).” Wistfully, he admitted that although none of his family members has ever been to Sialkot since his grandfather’s visit in 1957, he often thinks of visiting the city. “Few of my acquaintances with Partition history who have visited Pakistan say that nothing much has changed in the villages. I earnestly wish to go there and look at those houses, roads, and fields my parents so vividly described. Every time they spoke, they had a glint in their eyes — it felt as if they were reliving all memories of their past life, every time they spoke about it.”

Uncle’s fondness for Sialkot, the home he had never visited, was palpable. When I asked him if there was anything particularly “Sialkotia” in his house or upbringing, uncle replied that the way he spoke Punjabi was typical of Sialkot: If I were to talk to someone from Sialkot today, they wouldn’t be able to make out that I do not live there!” Uncle ended with a very heartwarming anecdote: “Just after Partition, when my bua (aunt-father’s sister) was to marry, she expressed her displeasure at the thought of marrying into ‘an East Punjab’ family [Punjab was partitioned in such a way that the Western half went to Pakistan and the Eastern was given to India], thus my grandfather found a family who had migrated from Sialkot just like us. Now it has become a tradition in our household: even when my son got married a few years ago, we especially looked for a girl whose family had migrated from Sialkot like us!”

EPILOGUE

The last incident that Uncle narrated left a smile on my face. When we had begun our conversation, it was difficult for me to understand how he could regard a city he had never been to but only heard of, his home. However, by the time he finished his story, I could see how Uncle indeed was a true Sialkotia. Partition may have severed his family’s physical ties to the city, but they had managed to, over two generations, maintain a much deeper connection to Sialkot . This highlights how important a role oral memories play, especially when physical movement is not possible. Uncle’s recounting of his infant brother’s death during their migration had stirred a horrifying montage in my head and one can’t even imagine how his family would have dealt with that devastating reality. However, they had never let it mar their association with Sialkot, even ingraining the love that they had for their city in their children. I dedicate this blog to Uncle and his family’s love for their cherished city and home–Sialkot.